Adultery — defined in Jewish law as sexual relations between a married woman and a man not her husband — is viewed in Jewish tradition as a sinful act of the utmost seriousness. It is one of the Ten Commandments and, along with other forbidden sexual relations, one of Judaism’s three cardinal sins that one is forbidden to transgress even at the cost of one’s life. The prohibition is included in the so-called Holiness Code, a section of Leviticus that features many laws aimed at distancing the Israelites from vulgarity, and is described in Genesis 20:9 as a “great sin.”

According to the , both the adulterous woman and the man she sinned with are liable for the death penalty. (Relations between a married man and an unmarried woman are rabbinically prohibited, but do not qualify as adultery by the biblical standard.) In practice, as with all capital crimes in Judaism, this sentence was rarely meted out. But taken together with the Bible’s other pronouncements on adultery, it makes clear the severity with which this transgression was viewed.

The Torah does not say why only a married woman having sex outside the confines of marriage is considered adulterous, but the marital norms in biblical times offer a clue. Several biblical figures are known to have had sexual partners other than their wives, including two of the three patriarchs. Traditional Jewish law also sometimes regards marriage as an acquisition of sorts, in which a woman is permitted to her husband and forbidden to all other men — in effect, she belongs to him, but he does not belong to her. Questions of paternity raised by a woman having multiple partners may also have contributed to the taboo on adulterous relationships. “So [God] wanted that the seed of men be known to whom it is, and not that they be mixed one with the other,” states Sefer Hachinukh, a 13th-century rabbinic text.

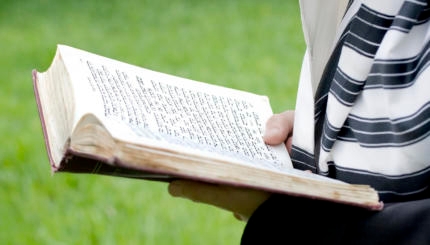

Whatever the reasons, the prohibition is considered a severe one, and mere suspicion that it has been violated gives rise to one of the strangest rituals in Judaism, the ordeal of the sotah — a practice described in the fifth chapter of the Book of Numbers and elaborated on at length in the , which devotes an entire tractate to the subject. According to the biblical account, if a woman commits adultery but there are no witnesses to the act, her husband may bring her to the priest, who has the accused drink a potion made from earth from the Temple and dissolved ink. If the woman is guilty, “her belly shall distend and her thigh shall sag; and the wife shall become a curse among her people.” If she is innocent, she will be unharmed.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Expressly reliant on supernatural intervention, the sotah ritual is unlike anything else prescribed in the Torah and has not been practiced at least since mishnaic times. The detailed version of the ritual described in the Mishnah includes public humiliation of the woman before her guilt or innocence has been determined, leading many modern readers to see it as an example of a patriarchal culture treating a woman far more harshly than a man in the face of an alleged sexual crime to which they were both parties. Others have portrayed it not as a way to punish a promiscuous woman, but of exonerating an innocent one, thus preserving the sanctity of her marriage. However it’s understood, it is yet another marker of how serious an infraction adultery was seen by ancient Jews.

The major Jewish commentaries offer several suggestions for why this is so. The Midrash notes that the Ten Commandments were given on two tablets, which creates a parallel between those appearing opposite one another on the stones. Adultery is inscribed opposite the commandment not to have any gods other than God — i.e. idol worship — suggesting a connection between the two. This equation of adultery and idol worship is echoed in various biblical texts that compare Israel’s abandonment of God to an adulterous woman who is disloyal to her husband. The implication appears to be that disloyalty to one’s spouse is comparable to disloyalty to God. Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra, a 12th-century Spanish commentator, suggests that adultery is a violation of the commandment to love one’s fellow as oneself.

Modern writers often take the view that adultery is an assault on the sanctity of the family, a foundational institution of Jewish life. And indeed, if the adulterous union produces a child, that child is considered a mamzer, which historically meant they were barred from marrying other Jews and building more Jewish homes. Many contemporary Jewish communities have effectively done away with this category, but not all have, though the inherent ambiguity around paternity tends to make such a situation rare.