In the latter half of the twentieth century, a grass-roots movement of Jewish feminism sparked a move toward gender equality in the American Jewish community. Many Jewish women participated in what has been called the second wave of American feminism that began in the 1960s. Most did not link their feminism to their religious or ethnic identification.

But some women, whose Jewishness was central to their self-definition, naturally applied their newly acquired feminist insights to their condition as American Jews. Looking at the all-male bimah (stage) in the synagogue, they experienced the feminist “click”—the epiphany that things could be different—in a Jewish context.

1970: The Beginning of Jewish American Feminism

Two articles in particular pioneered feminist analysis of the status of Jewish women. In the fall of 1970, Trude Weiss-Rosmarin criticized the liabilities of women in Jewish law in her “The Unfreedom of Jewish Women,” which appeared in the Jewish Spectator, the journal she edited. Several months later, Rachel Adler, then an Orthodox Jew, published a blistering indictment of the status of women in Jewish tradition in Davka, a countercultural journal. Adler’s piece was particularly influential for young women active in the Jewish counterculture of the time.

In the early 1970s, Jewish feminism moved beyond consciousness-raising discussion groups and collectives to challenge established Jewish institutions and practices. Calling themselves Ezrat Nashim, a small study group of young feminists associated with the New York Havurah, a countercultural fellowship designed to create an intimate community for study, prayer, and social action, took the issue of equality of women to the 1972 convention of the Conservative Rabbinical Assembly. The founding members of Ezrat Nashim represented the highly educated elite of, primarily, Conservative Jewish youth.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

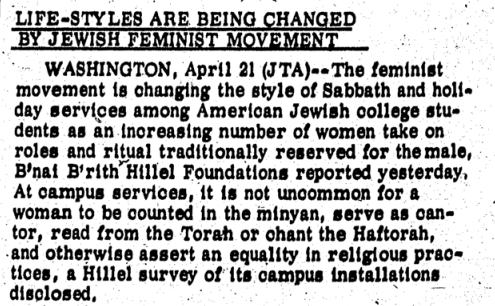

In separate meetings with rabbis and their wives, the women of Ezrat Nashim issued a “Call for Change” that put forward the early agenda of Jewish feminism. That agenda stressed the “equal access” of women and men to public roles of status and honor within the Jewish community. It focused on eliminating the subordination of women in Judaism by equalizing their rights in marriage and divorce laws, counting them in the minyan (the quorum necessary for communal prayer), and training them for positions of leadership in the synagogue as rabbis and cantors. In recognition of the fact that the secondary status of women in Jewish law rested on their exemption from certain mitzvot (commandments), the statement called for women to be obligated to perform all mitzvot on the same level as men. Ezrat Nashim caught the eye of the New York press, which widely disseminated the demands of Jewish feminism.

Jewish feminism found a receptive audience. In 1973, secular and religious Jewish feminists, under the auspices of the North American Jewish Students’ Network, convened a national conference in New York City that attracted more than five hundred participants. A similarly vibrant conference the following year led to the formation of a short-lived Jewish feminist organization. Although Jewish feminists did not succeed in establishing a comprehensive organization, they were confident that they spoke for large numbers of women (and some men) within the American Jewish community.

Early Strategies of Jewish Feminists

Feminists used a number of strategies to bring the issue of gender equality before the Jewish community. Feminist speakers presented their arguments from the pulpit in countless synagogues and participated in lively debates in Jewish community centers and local and national meetings of Jewish women’s organizations. Jewish feminists also brought their message to a wider public through the written word. Activists from Ezrat Nashim and the North American Jewish Students’ Network published a special issue of Response magazine, devoted to Jewish feminism, in 1973. With Elizabeth Koltun as editor, a revised and expanded version, entitled The Jewish Woman: New Perspectives, appeared in 1976. That year, Lilith, a Jewish feminist magazine, was established by Susan Weidman Schneider and Aviva Cantor; Schneider has served as its editor since that time. Lilith combines news of interest to Jewish women with articles and reviews of new publications, bringing to a lay audience the latest Jewish feminist research in a popular form.

The very lack of formal Jewish feminist organizational structures in the early years allowed for grass-roots efforts across the country. In 1977, for example, Irene Fine of San Diego, California, established the Woman’s Institute for Continuing Jewish Education. Not only did this organization regularly bring speakers and artists to southern California, it also published collections of women’s rituals and Jewish women’s interpretations of Jewish texts.

Through their publications and speaking engagements, Jewish feminists gained support. Their innovations—such as baby-naming ceremonies, feminist Passover seders, and ritual celebrations of Rosh Chodesh (the new month, traditionally deemed a woman’s holiday)—were introduced into communal settings, whether through informal gatherings in a home or in the synagogue. In a snowball process, participants in the celebration of new rituals spread them through word of mouth. Aimed at the community rather than the individual, new feminist celebrations designed to enhance women’s religious roles were legitimated in settings that became egalitarian through the repeated performance of these new rituals. Indeed, one of the major accomplishments of Jewish feminism was the creation of communities that modeled egalitarianism for children and youth.

Ordaining Women as Rabbis and Cantors

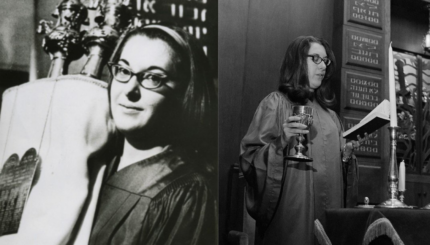

The concept of egalitarianism resonated with many American Jews, who recognized that their own acceptance as citizens was rooted in Enlightenment views of the fundamental equality of all human beings. With growing acceptance of women in all the professions, the Reform Movement, which rejected the authority of halakhah (Jewish law), acted on earlier resolutions that had found no obstacles to women serving as rabbis. Hebrew Union College, the seminary of the Reform Movement, ordained the first female rabbi in America, Sally Priesand, in 1972, and graduated its first female cantor in 1975. The Reconstructionist Movement followed suit, ordaining Sandy Eisenberg Sasso as rabbi in 1974.

Women’s Struggle to be Ordained by the Conservative Movement

Although the issue of women’s ordination was fraught with conflict for the Conservative Movement, it, too, responded to some feminist demands. In 1973, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Rabbinical Assembly ruled that women could be counted in a as long as the local rabbi consented. And the 1955 minority decision permitting women to receive aliyot was widely disseminated, leading to a rapid increase in the number of congregations willing to call women to the .

It took longer for women to be ordained as clergy in the Conservative Movement, then the largest denomination within American Judaism. Because the Conservative Movement considers halakhah binding but also acknowledges that Jewish law is responsive to changing social conditions and concepts, the decision to ordain women as rabbis and invest them as cantors had to be justified in halakhic terms. The combined impact of American and Jewish feminism on Conservative congregations and their rabbis led to a decision by the movement in 1977 to establish a national commission to investigate the sentiment of Conservative Jews on the issue. Holding meetings throughout the country, members of the commission heard the anguished testimony of women who felt ignored in public Jewish life, as well as statements of men offering their support. Although it took note of the arguments against ordination, in its report submitted early in 1979, the commission recommended the ordination of women.

The divisions within the Conservative Movement and among the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary, the movement’s educational institution responsible for the training of rabbis, led to the tabling of the issue, but it would not disappear. With strong support from the Rabbinical Assembly and ultimately from Chancellor Gerson Cohen, and after consideration of faculty position papers supporting and opposing women as rabbis, the faculty of the seminary voted in October 1983 to accept women into the rabbinical school as candidates for ordination. Amy Eilberg, who had completed most of the requirements for ordination as a student in the seminary’s graduate school, became the first female Conservative rabbi in 1985. Women were welcomed into the Conservative cantorate in 1987.

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.