Emma Goldman was born in Kovno, Lithuania, in 1869 into a religiously traditional household. As a teenager, she was deeply influenced by the Russian anarchist writers Chernyshevsky and Bakunin. When she expressed a desire for further education, her father told her, “Girls don’t have to learn much! All a Jewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare gefilte fish, cut noodles fine and give the man plenty of children.”

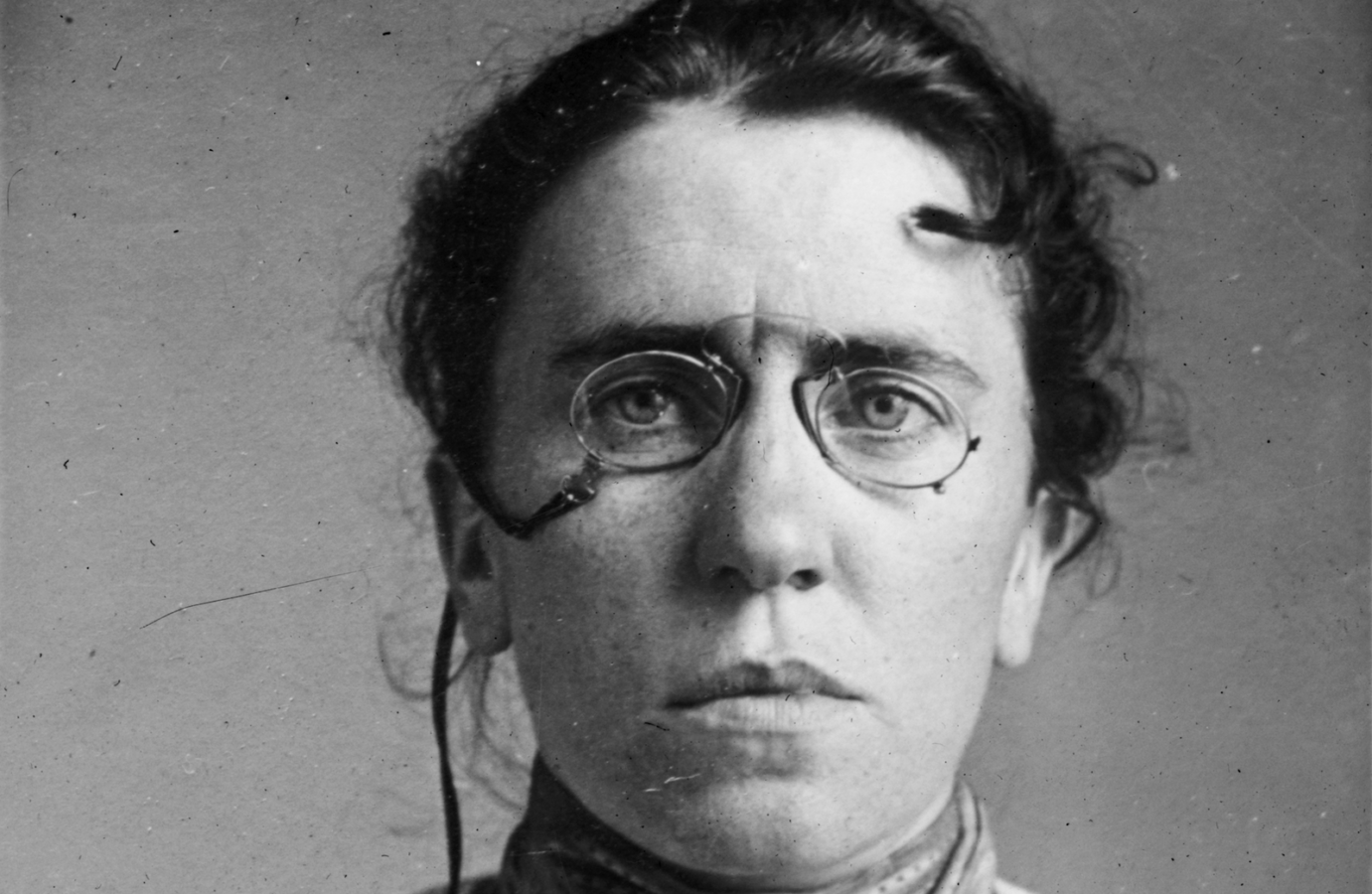

Rebelling against these limits, in 1885 the strong-minded 16-year-old Goldman left home and boarded a boat for America, the land of freedom. By the 1890s, Goldman won a reputation as “Red Emma,” perhaps the most notorious radical lecturer in the United States.

Lifetime of Advocacy

Goldman spent a lifetime agitating for values such as social justice for working people, the abolition of capitalism, freedom of spiritual and intellectual expression, free love and an end to war, racism, religious differences and ethnocentrism.

However, she never forgot her Jewish identity. While she was still a child, Goldman’s family was driven from Kovno to Konigsburg, Germany, and then to St. Petersburg, Russia, by anti-Semitic violence. Biographer Candace Falk notes that the biblical Judith, who cut off the head of Holofernes to avenge the wrongs done to the Jewish people, was Goldman’s female role model. Her experience of Russian violence against Jews informed her lifelong advocacy for social justice.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

When she arrived in America in 1885, Goldman settled in Rochester, NY, where she worked in the garment industry and married Jacob Kersner. Soon afterwards, Goldman was further radicalized by the hanging of seven political anarchists who were convicted, on flimsy evidence, of killing seven police officers in an explosion in Chicago’s Haymarket Square.

For a time, Goldman tolerated near-starvation wages and marital strife, but in 1889 she divorced Kersner, packed her sewing machine and personal effects, and moved to New York’s Lower East Side in search of greater freedom and a larger platform for her anarchist views.

New York City

In New York City, anarchist newspaper editor Johann Most greatly influenced Goldman. Recognizing her charisma, Most encouraged the fiery Goldman to agitate among Yiddish-speaking workers for general strikes and the overthrow of the state. Beyond the usual anarchist protest against economic inequality, Goldman also called for “freedom, the right to self-expression [and] everybody’s right to beautiful things.” Goldman invoked the love of beauty and higher instincts that, she believed, are shared by all humans regardless of cultural background or economic status.

At this time, Goldman met and became involved with fellow anarchist Alexander Berkman. In 1892, they were incensed by the killing of strikers at Carnegie Steel’s Homestead plant, near Pittsburgh. Goldman funded Berkman’s purchase of the gun with which he wounded Henry Clay Frick, manager of Carnegie Steel, in a failed assassination attempt. Berkman was sentenced to life in prison and the United States government launched a crackdown on other anarchists.

One year later, Goldman was imprisoned for violating laws that prohibited anarchist speech. Goldman proclaimed that the government “can never stop women from talking.”

After her release from prison in 1895, Goldman ceased advocating for direct action, such as assassination and general strikes, and proclaimed instead that “the key to anarchist revolution was a revolution in morality… a conquest of the ‘phantoms’ that held people captive,” such as racism and religious intolerance. Goldman avoided arrest until 1917, when she was jailed for 18 months for speaking out against conscription in World War I.

Deportation

In 1919, the U. S. government deported her to Russia. Expecting to find freedom in the “workers’ paradise,” Goldman instead found Communist repression and lingering anti-Semitism. She openly criticized Lenin for his anti-democratic policies. Disillusioned, Goldman departed and spent her remaining days as a self-described “woman without a country.” She lived for a time in Republican Spain but fled when Franco’s fascists triumphed, moving to France. She spoke out against Stalin, Hitler, and all forms of totalitarianism.

In 1906, Goldman wrote optimistically, “Owing to a lack of a country of their own, [Jews] developed, crystallized, and idealized their cosmopolitan reasoning faculty… working for the great moment when the earth will become the home for all, without distinction of ancestry or race.” After her Soviet experience, however, she wrote: “When I was in America, I did not believe in the Jewish question removed from the whole social question. But since we visited some of the pogrom regions I have come to see that there is a Jewish question, especially in the Ukraine.… It is almost certain that the entire Jewish race will be wiped out should many more changes take place.”

Writing in 1937 after the rise of Hitler, Goldman’s Jewish identity found renewed expression: “While I am neither Zionist nor Nationalist, I have worked for the rights of the Jews and [against] every attempt to hinder their life and development.” According to biographer Falk, before she died in 1940 in Toronto, Emma Goldman — wandering Jew and anti-state radical — reluctantly acknowledged that her fellow Jews needed refuge somewhere in the world, a place of their own.

Goldman’s speeches and writings have inspired (for better or worse) a range of individuals from Leon Czolgosz, the 1901 assassin of president William McKinley; to Roger Baldwin, founder of the American Civil Liberties Union; to libertine novelist Henry Miller. In the 1960s and 1970s, her autobiography and her magazine, Mother Earth, inspired a new generation of New Leftists and feminists. Goldman’s legacy lives on.

Reprinted with permission from “Chapters in American Jewish History,” published by the American Jewish Historical Society.