Hanukkah is one of the few Jewish holidays not mentioned in the Bible. The story of how Hanukkah came to be is contained in the books of 1 and 2 Maccabees, which are not part of the Jewish canon of the Hebrew Bible.

These books tell the story of the Maccabees, a small band of Jewish fighters who liberated the Land of Israel from the Syrian Greeks who occupied it. Under the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Syrian Greeks sought to impose their Hellenistic culture, which many Jews found attractive. By 167 B.C.E, Antiochus intensified his campaign by defiling the Temple in Jerusalem and banning Jewish practice. The Maccabees — led by the five sons of the priest Mattathias, especially Judah — waged a three-year campaign that culminated in the cleaning and rededication of the Temple.

Since they were unable to celebrate the holiday of Sukkot at its proper time in early autumn, the victorious Maccabees decided that Sukkot should be celebrated once they rededicated the Temple, which they did on the 25th of the month of Kislev in the year 164 B.C.E. Since Sukkot lasts seven days, this became the timeframe adopted for Hanukkah.

Josephus’ Account

About 250 years after these events, the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote his account of the origins of the holiday. Josephus referred to the holiday as the Festival of Lights and not as Hanukkah. Josephus seems to be connecting the newfound liberty that resulted from the events with the image of light, and the holiday still is often referred to by the title Josephus gave it.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Talmud and the Miracle of Oil

By the early rabbinic period about a century later — at the time that the Mishnah (the first compilation of oral rabbinic law included in the Talmud) was redacted — the holiday had become known by the name of Hanukkah (“Dedication”). However, the Mishnah does not give us any details concerning the rules and customs associated with the holiday.

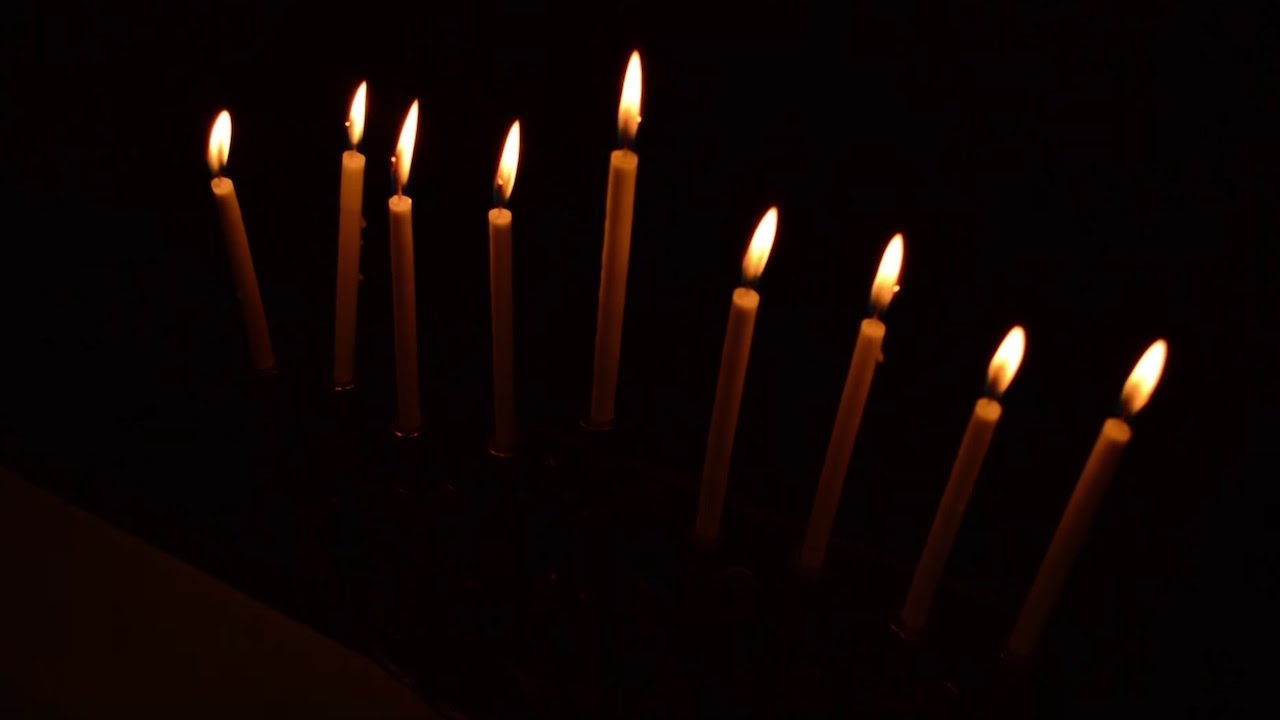

It is in the Gemara (a commentary on the Mishnah) of the Babylonian Talmud that we are given more details and can clearly see the development of both the holiday and the stories associated with it. The discussion of Hanukkah is mentioned in Tractate Shabbat. Only three lines are devoted to the events of Hanukkah while three pages detail when, where and how the Hanukkah lights should be lit.

READ: 9 Things You Didn’t Know About Hanukkah

Completed approximately 600 years after the events of the Maccabees, the Talmud contains the extant version of the famous story of the miraculous jar of oil that burned for eight days. The Talmud relates this stories in the context of a discussion about the fact that fasting and grieving are not allowed on Hanukkah. In order to understand why the observance of Hanukkah is so important, the Rabbis recount the story of the miraculous jar of oil.

Perhaps the Amoraim — the sages of the Talmud — were retelling an old oral legend in order to associate the holiday with what they believed to be a blatant, supernatural miracle. Although the seemingly miraculous victory of the Maccabees over the Syrian Greeks was certainly part of the holiday narrative, this event still lies within the natural human realm. The Rabbis may have felt this to be insufficient justification for the holiday’s gaining legal stature that would prohibit fasting and include the saying of certain festival prayers. Therefore the story of a supernatural event centering on the oil — a miracle — would unquestionably answer any concerns about the legitimacy of celebrating the holiday.

Hanukkah in Modern Times

Hanukkah gained new meaning with the rise of Zionism. As the early pioneers in Israel found themselves fighting to defend against attacks, they began to connect with the ancient Jewish fighters who stood their ground in the same place. The holiday of Hanukkah, with its positive portrayal of the Jewish fighter, spoke to the reality of the early Zionists who felt particularly connected to the message of freedom and liberty.

READ: 8 Hanukkah Traditions From Around the World

Hanukkah began to find new expression in the years leading up to the founding of the modern State of Israel. In the post-Holocaust world, Jews are acutely aware of the issues raised by Hanukkah: oppression, identity, religious freedom and expression, and the need to fight for national independence. Hanukkah has developed into a holiday rich with historical significance, physical and supernatural miracle narratives, and a dialogue with Jewish history.

Read more from our partner sites Kveller, Hey Alma and The Nosher:

The History of Hanukkah Donuts

The Fascinating History of Hanukkah Merch in America

Explore Hanukkah’s history, global traditions, food and more with My Jewish Learning’s “All About Hanukkah” email series. Sign up to take a journey through Hanukkah and go deeper into the Festival of Lights.

Hanukkah

Pronounced: KHAH-nuh-kah, also ha-new-KAH, an eight-day festival commemorating the Maccabees' victory over the Greeks and subsequent rededication of the temple. Falls in the Hebrew month of Kislev, which usually corresponds with December.

Kislev

Pronounced: KISS-lev, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish month usually coinciding with November-December.

menorah

Pronounced: muh-NOHR-uh, Origin: Hebrew, a lamp or candelabra, often used to refer to the Hanukkah menorah, or Hanukkiah.

Mishnah

Pronounced: MISH-nuh, Origin: Hebrew, code of Jewish law compiled in the first centuries of the Common Era. Together with the Gemara, it makes up the Talmud.

Sukkot

Pronounced: sue-KOTE, or SOOH-kuss (oo as in book), Origin: Hebrew, a harvest festival in which Jews eat inside temporary huts, falls in the Jewish month of Tishrei, which usually coincides with September or October.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.