Commentary on Parashat Shemot, Exodus 1:1 - 6:1

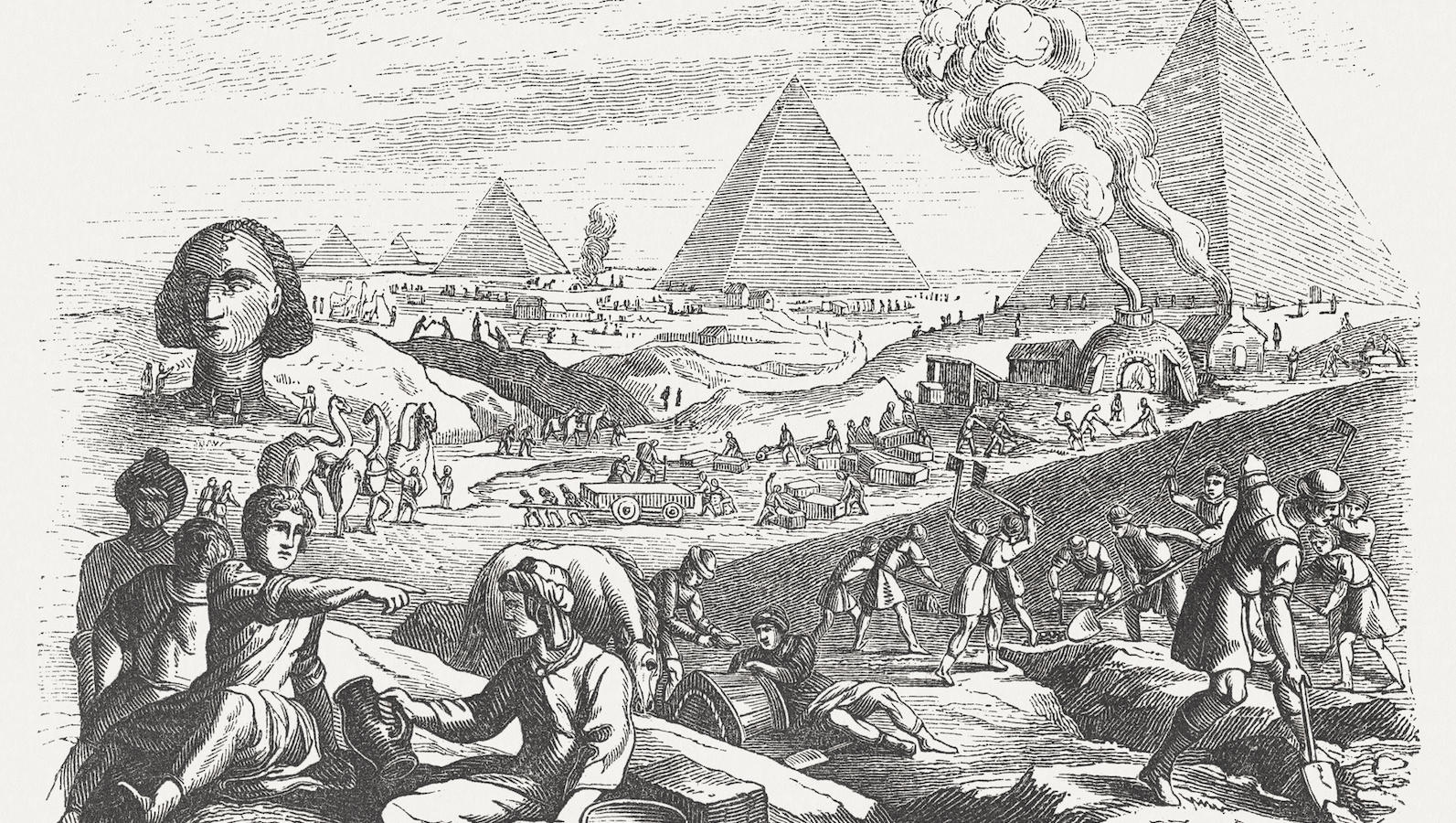

- The new king of Egypt makes slaves of the Hebrews and orders their male children to be drowned in the Nile River. (1:1-22)

- A Levite woman places her son, Moses, in a basket on the Nile, where he is found by the daughter of Pharaoh and raised in Pharaoh’s house. (2:1-10)

- Moses flees to Midian after killing an Egyptian. (2:11-15)

- Moses marries the priest of Midian’s daughter, Zipporah. They have a son named Gershom. (2:16-22)

- God calls Moses from a burning bush and commissions him to free the Israelites from Egypt. (3:1-4:17)

- Moses and Aaron request permission from Pharaoh for the Israelites to celebrate a festival in the wilderness. Pharaoh refuses and makes life even harder for the Israelites. (5:1-23)

Focal Point

A new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. And he said to his people, “Look, the Israelite people are much too numerous for us. Let us deal shrewdly with them, so that they may not increase; otherwise in the event of war, they may join our enemies in fighting against us and rise from the ground.” So they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor; and they built garrison cities for Pharaoh: Pithom and Raamses. But the more they were oppressed, the more they increased and spread out, so that the [Egyptians] came to dread the Israelites. (Exodus 1:8-12)

Your Guide

Does the text mean to suggest that it was the memory of Joseph that had kept the Israelites safe from oppression in Egypt? In other words, was the hatred always there just below the surface, waiting for the opportunity to arise?

How were the Egyptian people complicit in Pharaoh’s evil scheme? Why did all the people of Egypt go along with it?

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

At what point does a stranger or immigrant become an inclusive member of society, no longer seen as an outsider?

What is it about the historical experience of the Jewish people that would cause them to harden and become resilient in the face of oppression?

By the Way…

“A new king arose over Egypt…” Rab and Samuel [differ in their interpretation]. One said that he was really new, while the other said that his decrees were made new. He who said that he was really new did so because it is written, “new;” and he who said that his decrees were made new did so because it is not stated that [the former king] died and he reigned [in his stead]. “Who did not know Joseph:” He was like one who did not know [Joseph] at all. (Talmud, Sotah 11a)

“Come, let us deal shrewdly with him.” It should have been with them! R. Hama b. Hanina said, [Pharaoh meant,] Come and let us outwit the Savior of Israel. With what shall we afflict them? If we afflict them with fire, it is written: For behold, Adonai will come with fire, and it continues, for by fire will Adonai plead. [If we afflict them] with the sword, it is written: And by His sword with all flesh. But come, and let us afflict them with water, because the Holy One, blessed be God, has already sworn that He will not bring a flood upon the world, as it is said: For this is as the waters of Noah unto Me… (They were unaware, however, that God would not bring a flood upon the whole world but upon one people God would bring it; or alternatively, God would not bring [the flood] but they would go and fall into it. Thus it says: And the Egyptians fled toward it. (Talmud, Sotah 11a)

Writer’s note: here the Talmud presupposes that the Egyptians knew Jewish tradition and God’s decree not to bring a flood again. Thus they thought to exploit this opportunity, thinking they were safe from God’s divine wrath. Instead, God turned the tables on them and punished them with the thing from which they thought they were safest. This may explain why the Egyptians felt safe to follow the Israelites into the parted Red Sea.

The root and beginning of this indescribable maltreatment was the supposed lack of rights of a foreigner… In Egypt, the cleverly calculated lowering of the rights of the Jews on the score of their being aliens (foreigners) came first; the harshness and the cruelty followed by itself, as it always does and will, when the basic idea of right has first been given wrong conception. (S. R. Hirsch, translator, “Exodus,” The Pentateuch, L. Honig and Sons, Ltd., London, England, 1959)

Historian Barbara Tuchman identifies three “principles” regarding anti-Jewish sentiment: (1) “It is vain to expect logic–that is to say, a reasoned appreciation of enlightened self-interest” when it comes to anti-Semitism. (2) Appeasement is futile. “The rule of human behavior here is that yielding to an enemy’s demands does not satisfy them but, by exhibiting a position of weakness, augments them. Its does not terminate hostility but excites it.” (3) “Anti-Semitism is independent of its object. What Jews do or fail to do is not the determinant. The impetus comes out of the needs of the persecutors and a particular political climate.” (Newsweek, February 3, 1975)

Your Guide

How has this pattern of “What have you done for me lately” anti-Semitism (described in Talmud, Sotah 11a) repeated itself throughout Jewish history?

How does the government-sponsored maltreatment of a particular group contribute to the development of a mob mentality? How does it encourage mistreatment of that group by others?

How did the lack of response of the Jewish community in Egypt contribute to its subjugation?

D’var Torah

In the Ten Commandments we find two statements of the commandment concerning Shabbat. Shamor, “Guard,” and Zachor, “Remember” the Sabbath Day. While this commandment refers to Shabbat, it may be understood with regard to the blessed memory of those who came before us.

In the case of Joseph, how might things have gone differently had the Israelites better guarded and remembered him and his contribution? Nowhere in the text do we read of how they expended their political capital to fend off Pharaoh’s harsh decree. The community had not renewed its engagement in Egyptian society: It had not built political bridges, developed new leadership, woven themselves into the fabric of society beyond being a labor force; it was therefore ripe for exploitation.

It is a reminder for every generation of the commandment al tifrosh min hatzibor, (“Don’t separate yourself from the community”). This is not only a commandment to the individual Jew with regard to the Jewish community but also to the Jewish community as a whole not to grow too distant from the society in which it lives and works.

Provided by the Union for Reform Judaism, the central body of Reform Judaism in North America.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.