There are some people it’s hard to argue with and win: your mother, Cubs fans, and people who accuse you of self-hatred. The last, of course, is an intractably loaded allegation–especially for Jews, for whom debates about allegiance to the Jewish people or the State of Israel hold profound political and personal implications. These days, when debaters pull the self-hatred card in debates over Middle East politics or Jewish continuity, the term takes over the argument, virtually rendering all retorts empty. Invariably, the more you protest, the more you indict yourself.

The Roots of the Term “Self-Hatred”

Today, accusations of Jewish self-hatred are most commonly levied in discussions of Israel and Zionism. Interestingly, the modern concept of Jewish self-hatred actually has its roots in early debates about political Zionism, where the groundwork for its use was laid by Theodor Herzl, founder of modern Zionism.

In his seminal 1896 book The Jewish State, Herzl criticized enemies of his plan to create a Jewish state in Palestine, calling them “disguised anti-Semites of Jewish origin.” A mere two years later, in 1898, Karl Straus — an opponent of Zionism — turned the term back on its creator, suggesting that, like traditional anti-Semites, Herzl was preoccupied with Jewish difference, and wanted only to remove Jews from Europe.

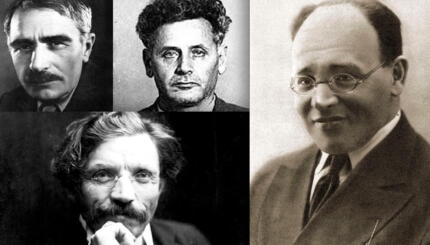

However, it wasn’t until 1930, with the publication of Theodore Lessing’s book Juedischer Selbsthass, translated as “Jewish Self-Hatred,” that the precise term came into vogue. In it, Lessing, a German Jewish philosopher and newly minted Zionist, slung the term “self-hating Jew” at academics opposed to Zionism.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

For Lessing, who had years before converted to Christianity and then returned to Judaism, discovering anti-assimilationist Zionist literature was a turning point, which ultimately led him to write this book urging Jews to repudiate assimilation and embrace their Jewish roots. He took aim at German Jews who had chosen to distance themselves from Judaism, but he also believed that self-hatred was unfortunately equal opportunity, and could be found in any minority group discriminated against by the majority.

Self-Loathing in America

The term “self-hatred” was popularized in the United States in the 1940s, when it first appeared in an essay written by psychologist Kurt Lewin “Self-Hatred among Jews” in Contemporary Jewish Record, in 1941. The essay was more widely distributed when it was published with a collection of Lewin’s other essays in his book, Resolving Social Conflicts, in 1948. Lewin, a German Jew who immigrated to the US in 1932, explained Jewish self-hatred as a phenomenon in which Jews, regarded as a minority or “other” by the host societies they lived in, resented and distanced themselves from all things Jewish. In other words, Lewin claimed, Jewish self-hatred occurs when society marginalizes Jews, who then internalize the sense of marginalization.

More recently, Professor Sander Gilman, an American cultural historian and the author of Jewish Self-Hatred, (1986), has similarly noted that Jewish self-hatred occurs in the spaces between “how Jews see the dominant society seeing them, and how they project their anxiety about this manner of being seen onto other Jews as a means of externalizing their own status anxiety.”

Labeling As a Weapon

The term “Self-Hating Jew” has been leveled at numerous Jewish figures over the last 100 years, most often condemning the actions or attitudes of those who hold offensive political agendas or whose critiques of Judaism pose a threat to the community. Among the most notable is Jewish pornographer and publisher Sam Roth, whose 1930 anti-Semitic screed Jews Must Live was so vitriolic that it was quoted at Nazi rallies. In it, Roth claimed that Jews were lazy, greedy parasites who preyed on the host cultures in which they lived.

Less extreme but just as controversial have been portrayals of American Jews by authors like Philip Roth (Portnoy’s Complaint, 1969), Henry Roth (Call it Sleep, 1934), and I.J. Singer (The Family Carnovsky, 1943), all of whom have been criticized for perpetuating and reiterating anti-Semitic stereotypes in their novels. Philip Roth’s Alexander Portnoy, critics suggested, reinforced claims that Jewish men were sexually deviant and inclined to prey on gentile women, while Henry Roth’s David Schearl was portrayed as having an Oedipus complex and living in a world of tremendous poverty and filth. Singer was labeled self-hating for creating a father character who was imagined by his son as both hypersexual and threatening, which led, in turn, to a Jewish son with an Oedipus complex.

Accusations of Jewish self-hatred are also common in contemporary debates about Israel. Jews who have struggled with, challenged, or questioned Israeli military or government actions or policies have often been labeled self-hating. Academics and politicians as diverse as Noam Chomsky, Michael Lerner, and Tony Judt have been called self-haters for criticizing Israeli policies.

Dealing with Accusations

A pointed example of how many Jews have dealt with the self-hatred label may be found in playwright Tony Kushner’s response to accusations that his play Caroline or Change was self-loathing. In the central conflict of the play, Noah Gellman, the son of the Jewish family that employs Caroline, an African-American housekeeper, is told that when and if he leaves change in the pockets of his clothing, it will be given to Caroline. Hedy Weiss, theater critic for the Chicago Sun Times, decried the play, and its implications, as anti-Semitic, perpetuating stereotypes about Jews, money and racism. Kushner’s response was swift, and typical of those who have been similarly condemned:

In every religious or ethnic group, one finds irascible people who arrogate unto themselves the job of policing who is and who isn’t a good and loyal member of the community. Such people rarely contribute anything to the community other than pain, and always fail to understand that it is the heterogeneity of any community of people that gives it life. I am immensely proud of being Jewish…Nothing makes me prouder than hearing, as I often do, that my work is identified as Jewish-American literature. My anger at this critic and her editors for accusing me of hatred for the Jewish people — for my people — exceeds my abilities to express it.

The Legacy of Self-Hatred

Unsurprisingly, the legitimacy of the term remains controversial. Some scholars have claimed that by labeling another Jew self-hating, the accuser is claiming his or her own Judaism as normative — and implying that the Judaism of the accused is flawed or incorrect, based on a metric of the accuser’s own stances, religious beliefs, or political opinions.

By arguing with the label, then, the accused is rejecting what has been defined as normative Judaism. The term “self-hating” thus places the person or object labeled outside the boundaries of the discourse–and outside the boundaries of the community.

Of course, not everything is relative. Sam Roth and those like him might be fairly characterized as self-loathing: that is, Jews who not only feel shame about their roots, but embrace or promote anti-Semitic attitudes, rhetoric, and stereotypes in public forums. The trouble is in distinguishing between what are legitimately anti-Semitic stereotypes, and what are merely warring political perspectives.