Many people are surprised to learn that there is a Jewish deathbed confessional prayer called the Viddui. During the Yom Kippur Viddui, the whole congregation rises and symbolically beats its chest while confessing to an alphabetical series of sins. The Viddui recited at the end of life is very different; personal rather than communal, it acknowledges the imperfections of the dying person and seeks a final reconciliation with God.

Unlike the better-known Catholic ritual, reciting the Viddui has nothing to do with insuring the soul’s place in the “world-to come.” Nor does [its recitation], in any way, tempt fate. In the words of the [law code the] Shulchan Arukh:

“If you feel death approaching, recite the Viddui. Be reassured by those around you. Many have said the Viddui and not died, and many have not said the Viddui and have died. If you are unable to recite it aloud, say it in your heart. And if you are unable to recite it, others may recite it with you or for you.”

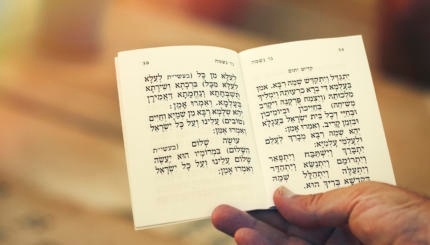

The prayer is recited when death seems imminent; it may be said by the [dying person], by family members, or by a rabbi. It can be read in Hebrew or English or in both languages. A formal Viddui can be read in sections, with pauses to let people speak from their hearts, to voice regrets or guilt, to ask forgiveness of one another, and to say “I love you.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Sign up for a Journey Through Grief & Mourning: Whether you have lost a loved one recently or just want to learn the basics of Jewish mourning rituals, this 8-part email series will guide you through everything you need to know and help you feel supported and comforted at a difficult time.

The Viddui can also be seen as a model for a less formal farewell. People at the bedside can sing a wordless melody–a niggun–saya few personal words of goodbye, and recite the Shema together: this, too, is a [kind of] Viddui.

However, as in all matters concerning the dying, the [dying person] is the one to decide on whether she wants to say or hear this prayer. The Viddui should never be imposed.

The central element of the Viddui is the Shema, the most familiar of all Jewish prayers and the quintessential statement of faith in God’s unity. The Shema is the last thing a Jew is supposed to say before death–which is also why it is recited before going to sleep at night (in case “I should die before I wake”). The Shema is not a petitionary prayer, nor does it praise God. It is a not really a prayer at all, but the proclamation of God’s oneness. It is also an affirmation of Jewish identity and connection.

The Shema ends with the word Echad, which means “One.” Uttered with “a dying breath,” it suggests the ultimate reconciliation of the soul with the Holy One of Blessing, Echad, whom Jews also call Adonai. In many ways, the Shema says “Yes.” In its own way, the Shema says “Amen.”

How To Say Viddui

מודה אני לפניך ה’ אלהי ואלהי אבותי שרפואתי ומיתתי בידך. יהי רצון מלפניך שתרפאני רפואה שלימה ואם אמות תהא מיתתי כפרה על כל חטאים ועונות ופשעים שחטאתי ושעויתי ושפשעתי לפניך ותן חלקי בגן עדן וזכני לעוה”ב הצפון לצדיקים

I acknowledge before You, Adonai, my God and God of my ancestors, that my recovery and my death are in Your hands. May it be Your will to heal me completely. And if I die, may my passing be an atonement for all the sins that I have committed, and grant me my portion in Gan Eden, and allow me to merit the World to Come, which has been reserved for the righteous.

If a person is too weak to say this entire paragraph, they can recite this sentence:

יהי רצון שתהא מיתתי כפרה על כל עונותי

May it be Your will that my death be an atonement for all my sins.

Excerpted with permission from Saying Kaddish: How to Comfort the Dying, Bury the Dead, and Mourn as a Jew (Schocken Books).

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.

Shema

Pronounced: shuh-MAH or SHMAH, Alternate Spellings: Sh’ma, Shma, Origin: Hebrew, the central prayer of Judaism, proclaiming God is one.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.