This piece is being published on the yahrzeit of Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi of blessed memory, may his teachings endure.

It begins like an old story. A reluctant maskil (a defender of the rational reform of Judaism, an “enlightener”) is strong-armed into visiting a chasidic rebbe. In Eastern Europe of yore, these meetings seldom ended well. Maskilim rejecting Hasidism as mystical hogwash for the masses, chasidim regarding maskilim as elitist heretics bent on zapping all magic out of Judaism.

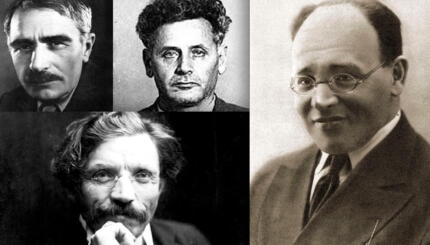

In this case, the rebbe was Reb Zalman and the maskil was myself. I was to serve as the translator for a virtual yechidus, an intimate one-on-one meeting, between Reb Zalman and a grateful Latin American student, Dr. Juan Jimenez Bravo. Some years before, the Renewal movement had received Dr. Jimenez’s community and affiliated them as one of their own. This is noteworthy because Dr. Jimenez’s community, Beith Etz Chaim, is not a suburban chavurah of baby boomers but a synagogue high up in the Peruvian Andes whose members are all converts to Judaism.

For the most part the members of Beith Etz Chaim are third- and fourth-generation descendants of Polish and Russian Jews –mostly men- who came to the city of Huanuco in Peru during the “rubber fever,” the boom in the rubber trade high in the Amazon at the beginning of the 20th century. High in the mountains, these Jews married local people and Judaism became a memory. Four generations later, their descendants are reclaiming their faith.

Far from an anomaly, the experience of Beith Etz Chaim is being replicated in cities and towns across Latin America. Claiming a long-lost Jewish heritage and wanting to reaffirm their identity, or simply seeking Judaism as a way of life and connection, thousands of Latin Americans have converted (or in some cases reverted) to Judaism. Most of them, unable to integrate into established existing communities, have opted to create their own. The Jewish mainstream across the denominations, both locally and internationally, has been slow to open the doors or lend a hand to these “emerging communities.” And yet, ahead of the curve, Reb Zalman had decided over six years ago to affiliate Beith Etz Chaim to the Renewal movement. Hearing that the rebbe was sick, my friend, Dr. Jimenez wanted to thank Reb Zalman personally for opening the doors for them.

Our conversation, which transpired a couple of months before Reb Zalman’s passing, was short and filled with interruptions. Skype did not behave well. Everything had to be said twice: in English and Spanish, and then back again. Still Reb Zalman’s really listened. He would smile as Dr. Jimenez spoke, repeating here and there the Spanish words he understood, and then as they would be translated, the smile would expand into a beam. Even though he did not understand most of what the first interlocutor was saying, he actively made both of us at ease.

More impressive than his laser-focused compassion, however, was his uncanny intuition. After hearing the history of the community, its struggles with isolation and discrimination, Reb Zalman took a short pause, breathed slowly through his oxygen tubes, and in 10 minutes proceeded to advice Dr. Jimenez about the future of his community. And although the conditions of this community are quite unique and out of most rabbis’ area of experience, Reb Zalman was spot-on in assessing their needs and desires. What had taken many of us working in the field a decade to learn, Reb Zalman gleaned in 10 minutes of intent listening. These are the three main pieces of advice he gave us that day.

Isolation can be a blessing. Many emergent communities lament that they do not have a reliable connection to the Jewish mainstream, both in their countries and abroad. While recognizing the need to establish Jewish connections, he also pointed out the great possibilities these emergent communities have of starting their Judaism without many of the prejudices and the encumbrances of the mainstream. Global Judaism, especially after the Shoah, needs Jews that are untainted by fear and pain. We need Jews that can bring some joy back to Judaism. He thought Latin Americans were providentially well disposed for this task.

Beware of labels. When we told Reb Zalman that many emergent communities were fighting among themselves about what patterns to follow, whether or Sephardic, Hasidic or Liberal, he laughed. The real strength of these communities would come in creating a renewed Judaism that organically fits their temperament, their gastronomy, their music; a Judaism that blossoms in the flavors and colors of the community’s surroundings. Emergent communities have the entire repository of Jewish wisdom and spiritual technology at their fingertips (even more so in a virtual age), and this should be the starting point. But where each community takes these building blocks is in their hands and in the hands of the Ribbono shel Olam, G-d almighty. At the end of the day, he said, the most successful model of growth is being true to your own nature. (Incidentally while discussing this, he made me aware that he had beaten me to the idea of using ponchos as talitot by almost three decades.)

Be visible and bold. In an interconnected age, emergent communities would be ill advised to cower in the corner trying to “get it right” before going public. The particular and ways of being Jewish that are to come from the mountains of Peru or the beaches of the Caribbean might be what is needed to nourish a distant community in Israel or America, or vice versa. Emergent communities need to use all the tools (especially those of global reach) to share their vision of Judaism with the world and connect to the organic matrix of belief and practices of Jewish peoplehood in which every community and generation is both a consumer but also a producer.

Looking back at his advice, it is clear that these guidelines are not only germane to emergent communities but also universally applicable. I was very impressed with my conversation with Reb Zalman, and I was greatly saddened when I heard of his passing some months later. And, though, I am still a maskil and far from being a Hasid, Reb Zalman’s insight on the particular communities that I serve have been an important guiding light in my work since, and on the anniversary of his departure, this precious Torah needs to be shared with as many people as possible.