This article was written for the 2009 Why Be Jewish Gathering: Renaissance in a Time of Ration, a project of The Samuel Bronfman Foundation’s Bronfman Vision Forum.

Let me begin by stating the obvious. When we speak of leaders, we are speaking about human beings. This is a self-evident but elusive fact of life; we know it and yet we consistently expect or imagine our leaders to be superhuman, and we are disappointed when they are not.

It is natural, when discussing leadership, to focus on what makes leaders exceptional. I want to begin our discussion of leadership, instead, by focusing on the shared humanity of those who assume leadership in a given situation, and those who are looking to others to provide leadership.

Why is this important as a starting place for our conversation about leadership? Because it reminds us of what leaders can and cannot offer.

Leaders cannot offer perfect guidance, certainty, or control. As human beings, we must stand humbly before the mystery of life and of death. We cannot anticipate the future, of course; but more than that, we cannot even hope to grasp the full meaning of what has passed, or to understand the infinite complexity of the moment in which we live. These are aspects of the human condition that we all share, though we experience and respond to them in different ways.

To make matters worse, we are each uniquely imperfect vessels, limited and flawed in our own particular ways. Our effectiveness as leaders depends, to a great extent, on our capacity to see, understand and respond compassionately to our own limitations and the limitations of others.

What, then, can a good leader offer? Leaders can help awaken, respond to and give direction to the basic human need for meaning and connection.

There are questions that beckon to each of us throughout our lives. Who am I? To whom am I responsible (or, who do I love?) What is my purpose?

At times, we are prepared to face these questions; at other times, for one reason or another, we may flee from them. But, for those who wish to engage in authentic and effective leadership – particularly religious leadership – the willingness to hear and respond to these questions with an open heart is essential.

By asking these questions, not just once but repeatedly, at critical junctures in our lives, we enhance our capacity to act with integrity and to effect positive change in the world and in the lives of those around us. We also invite others – through our example and influence – to engage in their own process of purposeful reflection and action.

This is what I have come to understand as the essence of good leadership. Ultimately, a leader is defined not by the exceptional qualities that she may exhibit, but by the positive qualities and actions that she inspires in others. A brilliant artist may be unappreciated during her lifetime, and only later recognized as a creative genius. But the standard by which a leader’s success must be measured is, by definition, relational. What matters most about a leader is what she brings out in others. The greatest leaders are not those who wield the most power, or even those who demonstrate the most impressive talents, but those who are able to elicit and inspire the very best in others.

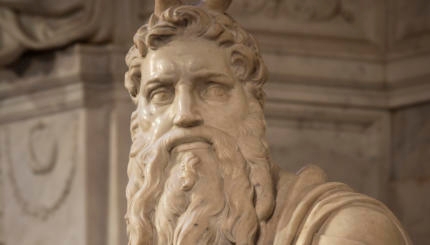

Two models of leadership take shape in the early chapters of the biblical Exodus narrative. Pharaoh represents one model: absolute in its assertion of power, breath-taking in its arrogance, life-denying in its rejection of all paradox and ambiguity. Moses represents a radically different model: a model founded on humility, interdependence, ambiguity, and an affirmation of the sanctity of human life.

Moses owed his life to Pharaoh’s daughter, who – with courage and compassion – saw the Hebrew child and “drew him forth†out of the waters of the Nile River. “She [Pharaoh’s daughter] named him Moshe, explaining, ‘I drew him forth’ from the water.†[Exodus 2:10] It is this act that constitutes one of the most important elements of true leadership – the act of seeing another and “drawing him forth†so that he can not only live but give new life. It is this act that gives Moses his name, and it is this act that ultimately defines his life’s work: to bring the people out of slavery not only in order to survive, but to serve and contribute to a greater purpose.

We are living in a historical moment of increasing scarcity and decreasing communal resources, but our human resources are as abundant as they have ever been – that is, endlessly abundant. The Jewish community can no longer afford to squander the enormous talent, creativity, and diversity that exist among us.

When I think about what it means for a leader to have vision, I think about two things: Can you see beyond what is to what might be, and can you see the person standing right in front of you? We need leaders with this kind of double vision. We need leaders who can see what each person has to offer and can help “draw them forthâ€, inspiring them to become creative contributors to the Jewish people and to the world.

Sharon Cohen Anisfeld is Dean of the Rabbinical School at Hebrew College in Boston. She received her rabbinical degree from the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.