I wrote my first novel standing in Herman Wouk’s shadow. Literally: I was in college at the George Washington University in D.C., an underweight kid living on friends’ couches who’d suddenly decided to be an observant Jew. There was only one Orthodox synagogue in walking distance, and it was like a rogues’ gallery of important Americans who happened to be religious Jews: Joe Lieberman, a senator who’d soon be nominated as a vice-presidential candidate; Leon Wieseltier, who was then writing a book called Kaddish.

And then there was Herman Wouk.

He was a writer, but an unpinnable one: he’d written doorstoppy masterpieces like War and Remembrance, a 1,056-page chronicle of World War II, but also short, sweet books like The City Boy, a story about one summer in an 11-year-old boy’s life, and Welcome to the Carnival, which Jimmy Buffett turned into a musical. And then there was This Is My God, the closest thing to an easy, accessible construction manual for Judaism as anyone’s ever put together. And he’d gotten his start writing gags for early Hollywood comics.

Wouk wasn’t an Orthodox Jewish writer; he was a writer who created beach novels and serious histories, who, on the side, just happened to be an Orthodox Jew. When I knew him, Wouk was in his late 80s; now, at 94, he’s still pumping out work.

His latest book,

The Language God Talks

, is nonfiction — a history of science, from the proto-nuclear 1940s through the golden Space Age of the 1980s, told from the viewpoint of someone who’s decisively not a scientist. In fact, it’s as much a meditation on scientists as scientific theory, a fan-letter to scientists such as Stephen Hawking and Steven Weinberg who easily and fluently explained scientific concepts to mass audiences. As Wouk freely acknowledges, it’s a fluency that does not work in both directions, as he’s spent most of his life trying, and failing, to wrap his head around the finer points of scientific theories.

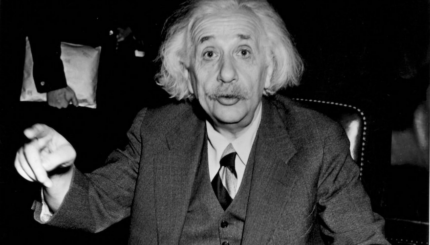

In fact, most of The Language God Talks‘s failings come at the high points of action. And, weirdly, I don’t mean this as criticism at all. When Wouk confesses that atomic-physics pioneer Richard Feynman’s explanations of atomic theory are more understandable and detailed than Wouk’s own, he doesn’t sound like he’s confessing — it’s more like he’s gushing. And when he notes that Albert Einstein‘s attempts to write a popular science book are inscrutable, he isn’t putting down Einstein — he’s warning us with the confidential advisory of two fanatics speculating about favorite baseball players, or stock tips.

What makes the book unique is, it’s coming from the opposite side of the screen than we’re used to. Histories and explanations of physics and natural phenomena are not rare, not even coming from scientists. Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time is an easy-to-understand bestseller. Einstein is quoted endlessly about the nature of God and science, and many more pithy sayings that simplify scientific ideas for the non-science-inclined. But Einstein was reticent to claim himself as a believer in God; Richard Feynman, one of Wouk’s idols, with whom this book begins and ends, skipped his own bar mitzvah, and, according to lore, refused even to say kaddish at his own father’s funeral.

It’s telling that, for a book subtitled On Science and Religion, there is so much science and so little religion — and yet so much of God. Alongside his biographical scientists, whom he describes tirelessly laboring to unravel the secrets of the natural universe, Wouk is kept endlessly enraptured; at each discovery, his heroes pause, marvel, and continue on with their work; Wouk is rendered metaphorically speechless and literally awe-struck, what Rabbi Nachman of Breslev would probably describe as divine flabbergast. It’s true how, as we learn more about the scope and form of the universe, we realize how truly unknowable it is.

Yet there’s plenty of bravado in this book, too. There’s something endearingly old-school about Wouk’s style in God Talks, both in the book’s candor and in its wit. One character he terms a “brainy maverick sea-dog,” and another, a secular astronomer, radiates “affable Jewish warmth.” His jovial, talky style poses alternately as self-deprecating and as authoritative old-timer; while meeting Neil Armstrong to discuss the possibility of a biography, they sip sodas in a coffee shop; he literally charms his way among the United States’ top-secret nuclear research scientists from the Manhattan Project (among them Feynman) by way of his World War II novels. In Feynman he finds, if not a friendship, then a mutual respect — a respect which permeates this book like nothing else. Not a chapter goes by without some quote or insight from Feynman; though they only met in person a few times in the 1950s, those encounters changed Wouk’s life, and rather than cliche or hyperbole, we travel through the ways that Feynman’s suggestions influenced the course of Wouk’s thought — and, though it would surely cause Feynman to roll over in his grave, Wouk’s religion as well.

More than anything else, The Language God Talks is a stream-of-consciousness piece, a short book that follows no guidance more than whatever happens to be on Wouk’s mind. There are 10-page digressions into the writing process behind Wouk’s early novels; his visits with the Chinese ambassador and his nephew — none of which are more than tangentially connected to the book’s theme. But as a meditation on the intersection of religion and science, of how things work and why they work, it’s an outstanding little book. It’s rare that we get to see inside someone’s head as clearly as this book lets us — and it’s rare that thoughts are as fully formed cogent as Wouk’s on science.