Jews read sections of the

each week, and these sections, known as

parshiyot, inspire endless examination year after year. Each week we bring you regular essays examining these portions from a queer perspective, drawn from the Torah Queeries online collection, which was inspired by the book Torah Queeries: Weekly Commentaries on the Hebrew Bible. This week, our reflection comes from Rabbi Rick Brody. Rabbi Brody first wrote this piece in 2006, so the time-line might feel a little off. We still think this is a relevant look at Parashat Shoftim and the idea of a just society.

It is amazing how procrastination affects one’s work. I began drafting this d’var Torah several days ago, but with the whirlwind of summer classes and make-up-work (Rabbinical school is not as glamorous as it seems) I hadn’t finished it by my “goal” date.

I had begun to write about the work of Citizens to Restore Fairness (CRF), a group in Cincinnati, Ohio, dedicated to protecting the rights of GLBTQ people in their city. In 2004, CRF successfully led a campaign to repeal a 12-year-old ordinance that outright denied gay people protections from discrimination. In March 2006, the Cincinnati City Council approved an anti-discrimination law, which would protect GLBT individuals from losing their jobs or being denied housing just for being queer. However, an anti-gay group, disguised as one committed to values, blocked the ordinance by petitioning to have the issue on the ballot. This summer, equality activists from across the country descended on Cincinnati to prepare for the November 7th election and to fight this anti-gay ballot measure. Uniting people across lines of race, class, gender and religion, this diverse group of people was working to bring justice to their community.

Then, this morning, the phone call came. “We won!” my girlfriend yelled, as she came running into the room. “What???” I replied, confused. Was this the Hebrew Union College softball team with its two-win record? No. “Citizens to Restore Fairness won!” she exclaimed.

As it turned out, the people so devoted to “community values” felt that signing the petition with fraudulent names, such as that of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, was an honest way of achieving their goals. With the petition proven corrupt the organization proposing the ballot measure withdrew and accepted defeat. We had achieved our goal: justice for the residents of Cincinnati; fairness for GLBTQ people in the city.

How does this relate to the d’var Torah I was writing? This week’s portion,

Parashat Shoftim

, or “magistrates,” is about creating a just society. It is part of Moses’ closing speech to the Children of Israel. The Israelites are standing and waiting to go into the Land, but Moses is unable to go with them. Because of Moses’ bad behavior in the desert, he will be left behind as the Israelites go on to the promised land.

In Moses’ speech, he provides ethical and administrative norms to be followed by the community. A dominant word within this parasha is tzedek, “righteous” or “justice.” The word occurs six times in the Torah and 68 times in the entirety of the

Tanakh

.

What is justice? Many modern Jews, myself included, take pride in our faith’s commitment to social change. “Social justice” has become a sort of buzzword for young Jewish activists working in a variety of fields. As a Reform rabbinical student, I take particular pride in my denomination’s leadership role in certain areas of social justice. The idea of a just society is rooted in our most holy text, the Torah. According to W. Gunther Plaut, a leading commentator on the Torah, “no people gave as much loving attention to the overriding importance of law equitably administered and enforced as did Israel.”

What, then, does a just society look like for LGBTQ people? This week’s Torah portion says “they shall govern the people with due justice” (Deuteronomy 16:18). Plaut suggests that this roots the ultimate administrative power in the people, rather than the king. This leads us to ask questions of our own lives. How can our leaders lead justly? How can we be leaders in our own community? How can the people create their own just society?

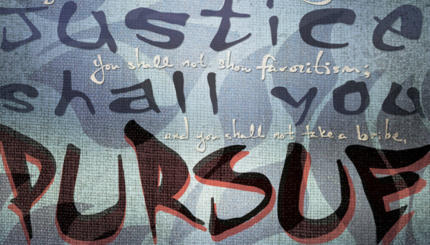

In Parashat Shoftim we are commanded “Tzedek tzedek tirdof” (“Justice, justice, you shall pursue,” Deuteronomy 16:20). The verb tirdof is in the imperative, commanding us to engage in the work at hand. Why does the word tzedek, “justice,” repeat twice? There is a Chassidic teaching that the word justice is repeated because “in matters of justice one may never stand still. The pursuit of justice is the pursuit of peace. Do justly so that justice may be engendered.”

We all must take a stand for justice wherever we see injustice taking place, not only for our own communities, but also for those in need of our support. The work of Citizens to Restore Fairness was accomplished through the work of people of all races, of many religions and across the entire spectrum of sexual orientation and gender identity. It is through embracing our diversity that we have the power to create change.

The words of Moses, whom the sages call Moshe Rabbeinu, or “Moses our teacher,” are instructive to all of us. Our Torah is our guidebook. Each year we read the text again, and each year it appears in a new light. Even though we have heard the stories before, they meet us where we are this year. Just as a parent lovingly guides a child towards the correct path, so too does our Holy text teach us. May we all be able to glean from its words the messages that will help us live our lives as better people and build a more just society: Ken yehi ratzon, may it be your will.

Like this post?