As I wrote in The Torch last fall, I started attending the early morning minyan at my synagogue with the vague idea of making Rosh Chodesh more meaningful and ended up attending throughout Elul, drawn by the call of the shofar.

Well, I still show up these many months later, with Shavuot just around the corner. What I wrote then was only part of the story. I also started attending out of a historian’s curiosity. One problem faced by medievalists is how to cross the bridge of time to arrive at a reasonable certainty that we comprehend the context of what we read, and not just the words. Because most of the books and manuscripts I read were written by religious men, I wondered whether participating in daily ritual would give me insight into those authors from hundreds of years ago. Communal prayer structured their lives from dawn until night, so maybe I would read through different eyes and hear with different ears if I made that structure my own.

Playing with sacred time comes naturally to Jews, for we believe that God acts in history. We repeatedly ask what it means to reenact and to relive. We sit in the sukkah to commemorate God’s compassion on our ancestors in the desert and to place our trust in God in the here and now. The Passover seder inevitably lends itself to discussions of history, tradition, and memory. Soon the Jewish community around the globe will celebrate Shavuot: we will stand at a Mount Sinai of several thousand years ago while at the same time renewing the covenant in hundreds of cities and towns in May 2015.

What I wanted, though, were not the red-letter days, but the everyday. I wanted not only the calendar of sacred time, but also its clock. I admit the idea was fanciful, and I never expected the experience to be more than suggestive. How can we pass from our world of computers, cell phones, and robot vacuum cleaners to one of manuscripts, camel caravans, and village wells? Grabbing my down parka and hopping into a minivan that will get me in three minutes to a warm synagogue with central heating is a lot different from trudging through the snow to a drafty wooden shtiebel with a temperamental wood-burning stove. Whether I learned anything about medieval history is doubtful.

I do keep learning about the eternal present, however. I have had time to reflect on the words of Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, which I came across back in the fall: “The prayer of women consists of only…the ‘service of the heart,’ the direct personal relationship to God—while the public, ceremonial aspect does not exist at all” [A Guide to Jewish Prayer, p. 27]. His discussion of women’s prayer is thoughtful and insightful—I certainly fit the profile of the older woman without small children at home who can adjust her work schedule to accommodate going to synagogue–but a recent discussion with a friend added another consideration.

This friend, a successful professional, described at some length how unsettling and uncomfortable it was to be the only woman at her synagogue when she went to say kaddish on her mother’s yahrzeit. She is no shrinking violet, is committed to women’s participation in the community, and probably was friendly with most of the men on the other side of the mechitza, yet for such an occasion she needed something from the community that wasn’t there. It occurs to me that when men go to synagogue for minyan, their concern is whether the ninth and tenth man will arrive, and in large congregations, even that rarely poses a problem. Women, on the other hand, wonder about the second woman. In other words, will any other woman be there? Men and women stood together when we accepted the Torah so many centuries ago. Perhaps we women have a public role in the synagogue today as well, at least for each other. As long as I show up, if a woman comes to the early minyan in my synagogue—whether to recite kaddish or attend a baby naming or hear the Torah reading or answer a compelling need to stand before God away from house or office–she will not be alone.

seder

Pronounced: SAY-der, Origin: Hebrew, literally “order”; usually used to describe the ceremonial meal and telling of the Passover story on the first two nights of Passover. (In Israel, Jews have a seder only on the first night of Passover.)

Shavuot

Pronounced: shah-voo-OTE (oo as in boot), also shah-VOO-us, Origin: Hebrew, the holiday celebrating the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai, falls in the Hebrew month Sivan, which usually coincides with May or June.

shtiebel

Pronounced: SHTEE-bull, Origin: Yiddish, a small synagogue.

sukkah

Pronounced: SOO-kah (oo as in book) or sue-KAH, Origin: Hebrew, the temporary hut built during the Harvest holiday of Sukkot.

Torah

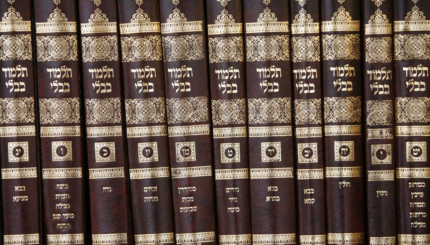

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.