The teachings transmitted by the rabbis in the centuries following the destruction of the Second Temple formed the core of what has come to be known as rabbinic Judaism, which still provides the framework for the various types of Judaism practiced today. The most widely studied of these rabbinic teachings are known collectively as the Talmud, which has two parts: Mishnah and .

The Mishnah is the earlier work, compiled from the teachings of sages living at the end of the Second Temple period and in the century following the destruction of the Temple.

A study book of laws and value statements that express the classical rabbis’ vision of Judaism, the ’s preoccupation is promotion of a religious and legal tradition both continuous with the past and practical for life in the post-destruction Diaspora. The Mishnah contains multiple opinions on many laws and does not often suggest which is the most authoritative. The plurality of Jewish practice is preserved in the text.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Gemara

Sages in both Babylonia (modern-day Iraq) and the Land of Israel continued to study traditional teachings, including the Mishnah, describing the teachings as having been passed down from Moses at Sinai (either literally or figuratively). The oral discussions were preserved, either by memorization or notation, and later edited together in a manner that places generations of sages in conversation with one another. These teachers were interested in bringing greater harmonization between biblical and rabbinic traditions, largely by providing proof-texts for known laws and explaining differences between the biblical and rabbinic versions of laws. This is the origin of the Gemara.

Babylonian vs. Palestinian

There are actually two works known as “Gemara” — the Babylonian Gemara (referred to as “Bavli” in Hebrew) and the Palestinian (or Jerusalem) Gemara (referred to as “Yerushalmi“). The term “Gemara” itself comes from the Aramaic root g.m.r (equivalent to l.m.d, in Hebrew), giving it the meaning “teaching.”

Although the Yerushalmi was completed earlier (with material spanning roughly 200-500 C.E.), it was eclipsed by the much longer Bavli (200-600 C.E.). The Bavli’s popularity may be due to the work of the Gaonim of Babylonia, who cited that work in the legal judgements (responsa) that they sent to communities throughout the Diaspora. Both Gemaras were written in a combination of Hebrew and Aramaic dialects and share the teachings of sages known by the term Amoraim (in the singular, Amora).

Both Broad and Deep

Gemara encompasses several literary genres, and subject matter ranges from the sacred to the profane. While it is often misrepresented as merely a commentary on the laws of the Mishnah, the Gemara has an intricate relationship with the Mishnah and a far greater scope. Although it is organized in accordance with the structure of the six orders of the Mishnah, mishnaic teachings are, for the Gemara, the launch pad for diverse topics: prayer, holy days, agriculture, sexual habits, contemporary medical knowledge, superstitions, criminal and civil law.

The Gemara contains both halakhah (legal material) and aggadah (narrative material). Aggadah includes historical material, biblical commentaries, philosophy, theology, and wisdom literature. Stories reveal information about life in ancient times, among Jews and between Jews and their neighbors, and folk customs. All of these genres are blended together with the halakhic material, in what is sometimes described as a stream-of-consciousness fashion filled with meaningful tangents and digressions.

The Relationship of Gemara to Mishnah

In dealing with the teachings of the Mishnah, the Gemara has multiple functions. It explains unclear words or phrasing. It also provides precedents or examples to assist in application of the law and offers alternative opinions from sages of the Mishnah and their contemporaries (known as Tannaim). Whereas the Mishnah barely cites biblical verses, the Gemara for nearly every law discussed introduces these connections between the biblical text and the practices and legal opinions of its time. It also extends and restricts applications of various laws, and even adds laws on issues left out of the Mishnah entirely (for example, the key observances of Hanukkah). Multiple opinions of sages are weighed against one another, often without presenting a conclusion.

How the Gemara is Studied

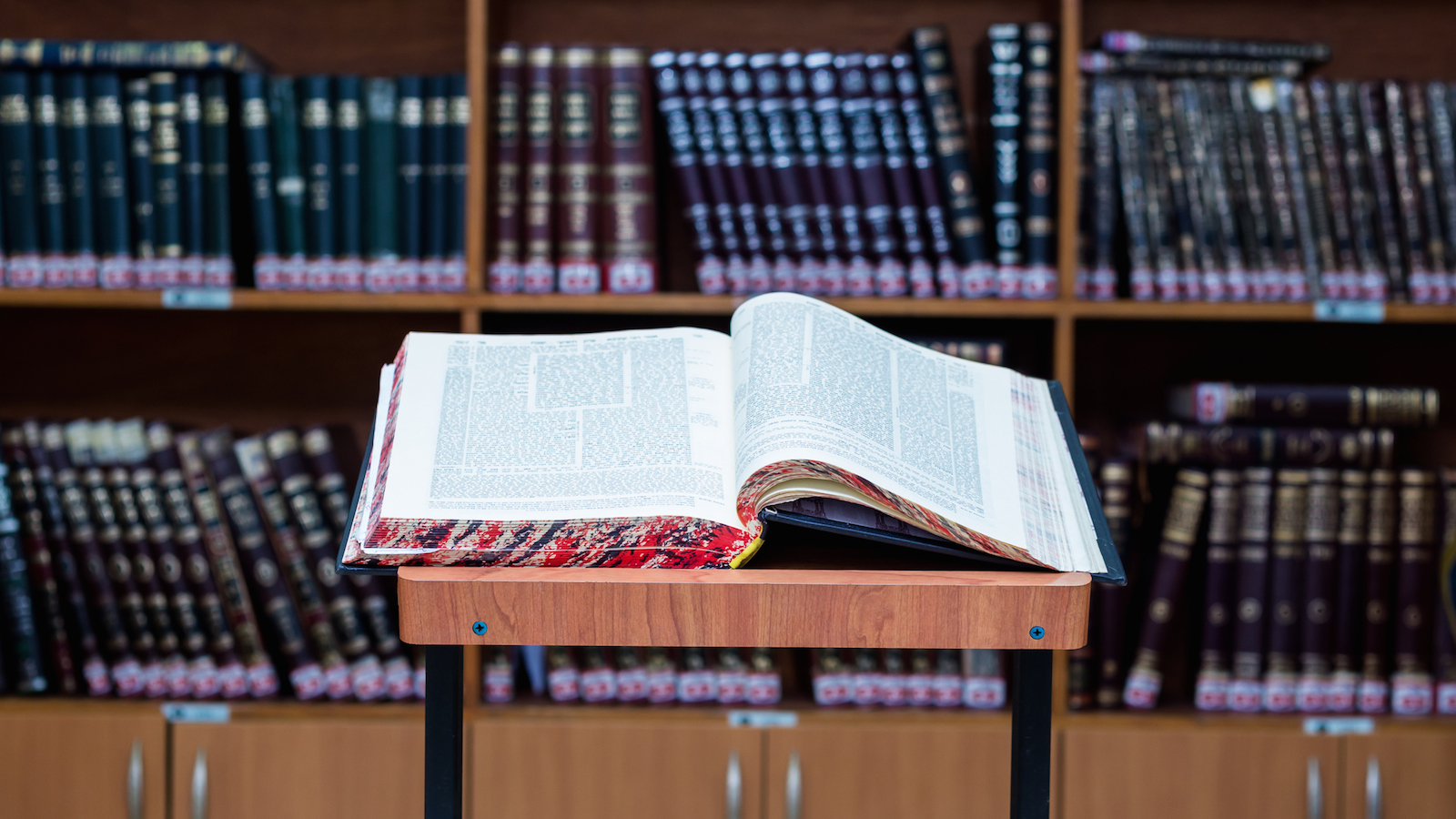

Talmudic teachings have been most often studied in groups or pairs– among masters and students and/or between two partners in learning. A pair of study partners is called a havruta. The havruta-style provides a challenging, lively, and intimate environment in which to explore the rich spiritual and intellectual depths of the Talmud.

yeshiva

Pronounced: yuh-SHEE-vuh or yeh-shee-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, a traditional religious school, where students mainly study Jewish texts.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.