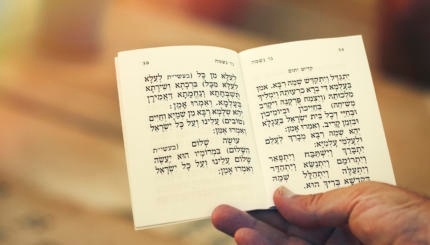

My father died on Rosh Hashanah 5764. He died at home, in a clean white bed, surrounded by his wife and all three of his children. As my family and I entered the state of aveylut, mourning, I was keenly aware of the intuitive and organic way the halakhot, Jewish laws, respected our grief and our fragility and at the same time ensured the honor of the departed soul. Reciting seemed to be part and parcel of that system. The graceful choreography of daily recitation and response of elevated words glorifying God dignified my feelings of grief and loss and gave me endless comfort.

My siblings are not traditionally observant, and I knew that if anyone was going to say Kaddish for my father, it would have to be me. When my father died, I was a mother of, and primary caregiver for, three young children, aged five, four, and two, so I decided that I would go to minyan (a daily prayer service) once a day.

I began my year attending shacharit (the morning prayer service) each morning at our synagogue. I was working from home that year, and had limited childcare for my two-year-old son Davi, so he was often my date to shacharit. Early minyan was out of the question due to morning school drop-offs for the other kids, so we went to the late minyan at 9 a.m., the one favored by retirees. Although I was typically the only woman in the room, my fellow minyan attendees welcomed me with open arms, never questioning my presence nor my recitation of Kaddish. But the unhurried pace of the minyan was not well-suited to mommy with a toddler in tow. By the time we got to the Kaddishes at the end of the service, Davi was DONE. He was either running around, crying, singing at the top of his lungs, or sometimes all three. I might have given up if not for the synagogue candy man. Beckoning to me through the mechitza (the divider in traditional synagogues between the men’s and women’s sections) he would take Davi out of the room to go get a lollipop so I could get through my Kaddish in peace. That seemingly simple act spoke volumes to me. He allowed me the dignity of reciting my Kaddish.

Once Daylight Savings Time arrived in the spring, I often attended mincha/ma’ariv (the afternoon/evening) services in the evening instead of shacharit services. Since mincha/ma’ariv began later due to the later sunset time, I had my husband at home ensuring no young companions in synagogue. Of course, I had to walk out of the house accompanied by the screams and cries of my “abandoned” toddler. “NO EMA (MOMMY) HADDISH! NO EMA HADDISH!” he would yell, tearing my heart to shreds. Inevitably, I would arrive at mincha a few minutes late to find the mechitza — a curtain on tracks attached to the ceiling, like at a doctor’s office or in an emergency room — flung open, and men occupying the tiny women’s section. As if leaving the screaming two-year-old wasn’t enough, I faced a group of men who, although they knew there was a good chance on any given day that I would be there saying Kaddish, refused to leave the women’s section intact so I would have a place to sit. Often, I would find myself in tears as I stood, burning with resentment, outside the beit midrash (study hall). Inevitably, after a moment or two (although it felt endless to me), someone would see me there, shoo the men out of the women’s section and pull the mechitza curtain closed so I could enter. But how to collect my thoughts and say Kaddish for my father with the appropriate kavanah, intention and focus, when my insides were churning? Rather than dignifying my grief, the process of reciting Kaddish began to tear me down.

Too emotionally exhausted to fight, I didn’t think there was anything I could do about the daily mincha/ma’ariv colonization of the women’s section, but my husband did. He contacted the rabbi, insisting that the women’s section should remain intact, regardless of whether any women were in attendance on any particular day. How can a synagogue call itself welcoming, he pointed out, if it literally had no place for 51 percent of the human race to sit at afternoon services? While the rabbi agreed in principle, he was unwilling to forbid the men from colonizing the women’s section when women were not there at the start of services. What was the point, he argued, of leaving an empty women’s section when there were plenty of men who needed the seats? He did not understand — nor did he care — that, by fostering a space that was so alienating to women, his synagogue perpetuated women’s absence at minyan. My husband tried to raise awareness by posting signs on the door of the beit midrash and on the curtain of the women’s section exhorting minyan attendees to keep the women’s section intact, but I often arrived at synagogue to find the signs torn down and the same men sitting in the women’s section. Looking back on it, I wonder why I didn’t stop going to minyan at that synagogue. But, as a busy mother of three young children, convenience was the driving force behind choosing a minyan — and like it or not, that synagogue had the most convenient service times and location for our family. My dignity took a back seat.

The tikkun, the reparative moment, came on my last day of the 11 months of reciting kaddish, Rosh Chodesh (the beginning of the new month of) Elul. The synagogue policy was that a man always needed to recite Kaddish along with me, which always made me feel like a small and irresponsible child. But on that day, the rabbi was not in attendance and when I started reciting Kaddish, no one joined with me. My heart swelling with emotion, I recited my last Kaddish for my father with dignity — clearly, loudly and all alone. After services, I walked out into the warm late summer evening, almost feeling my father’s soul alighting to heaven.

Looking for an Orthodox synagogue where women can recite Kaddish? Check out our list!