Disclaimer: In this unique blogpost, JOFA has provided a platform for how some women are considering dealing with the legitimate fear of becoming an agunah. All posts are contributed by third parties. The opinions and facts in them are presented solely by the authors, and JOFA assumes no responsibility for them.

I have nothing against committed relationships formed between consenting adults, but I take issue with the current form of Orthodox marriage. After 10 years of being an agunah (chained-woman) from two different husbands, I was not going to remarry a third time. By my mid-thirties I had two teenage children, had collected four gets (Jewish legal divorces) from two different men (two that I was happy with and two that were deemed acceptable by others), had my story recorded by the media, and had been excommunicated by parts of the religious community. I spent less than five years being in marriages and more than 10 years freeing myself from the institution of marriage. When the time came for me to formalize my third committed relationship at 36, I was not going to get married again. Now, close to 10 years and thank G-d four more kids later, I found something that works. It is not marriage and does not require a get. I am a pilegesh (concubine). Or as my oldest son says, my partner is “his mother’s concubine.”

READ: What Is An Agunah (Chained Woman)?

The problem with Orthodox Jewish marriage is that it involves the acquisition of a woman, and the marriage can only be absolved through a gett. To put it bluntly, Orthodox marriage is institutional slavery wrapped up in a nice bow. Religious pre-nups, which have helped many women, work as a civil bandaid on this religious construct. But no pre-nup can guarantee you will get a gett in a timely manner, which is a serious issue for women who still want to have children.

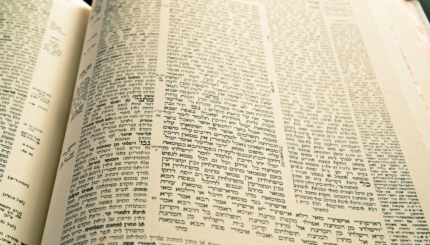

The Talmud as well as other Jewish legal texts describe various types of relationships between a man and a woman. Included in this list is pilagshut (having or being a concubine). In this type of a relationship, a contract is drawn to make it halakhically (legally) permissible for a man and woman to have sex. Such a couple does not have the benefits of marriage (spousal support, monogamy etc..), but either party may end the relationship at any given point. A gett is not required because you are explicitly not married. Since many of the benefits of Orthodox marriage (such as spousal support, child support, and inheritance) are guaranteed by civil law, it is conceivable to become civilly married while using the pilegesh construct to halakhically formalize a relationship.

When my partner and I decided to enter a committed relationship, we consulted my family rabbi — the same rabbi that conducted both of my marriages and divorces. Intimately aware of my painful history with marriage, he suggested that we use the pilegesh construct to formalize our relationship. This contract would stipulate our consensual, physical relationship, but it could also be used to outline the other terms of our relationship. This type of relationship offered me the opportunity to trade in being my husband’s property, for a negotiated contract that protects my right to end the relationship.

Our contract serves a purpose much greater than protecting me from needing a gett. It provides us with a tool to discuss, evaluate, and level our relationship on a regular basis. With full time jobs, four small children together, and two grown children from my first marriage, my partner and I live full, busy lives. The pace of this modern lifestyle has stripped families of their traditional roles, but has not replaced them with new ones. However our contract, which has been rewritten and signed over ten times (it expires every year by our choice), provides us with a framework for discussing the roles we play in our day to day lives.

The bulk of the contract is split into sections: self-care/exercise, community, family, religion, housework, finances, and personal/family goals. Not all of these are updated each year, but we always have a conversation about what’s working and what needs to change. We have had years where budgeting was the focus, and others where we were able and interested in hiring people to help with the house. We talk about how we are raising our kids, the importance of community, and how we want to engage the communities in which we live. We always specify a date night, as well as other ways we want to support each other. Because life changes all the time, the contract allows us to have an open discussion around what each partner is responsible for in the relationship.

Instead of a wedding or similar party, every year we have a “Celebration of Family” party to mark the fact that we have been a family for another year. We feel strongly in celebrating accomplishments instead of dreams, and every year as a family is an accomplishment. We created a commitment ceremony for family and friends after our second child was born. We selected a reading that was meaningful, then my partner and I discussed what family and our commitment to each other meant to us. We included an activity with my older children, and ended with another reading. We used the ceremony to recognize the blending of our families and the bonds that we formed.

For our family, the pilegesh contract provides us with a tool to stay connected to what is important to us as a couple and as individuals. It is the basis of our committed relationship to each other and to our children. It allows us to renegotiate our roles in a non-threatening consistent manner as our lives change.

The purpose of this blog post is to encourage others to consider alternative types of relationships that could offer more protection to women who wish to be in committed relationships. I am not a rabbi, and I am not here to defend the halakhic legitimacy of the pilegesh construct. I am making a social case for a solution that works for me. Regardless of marital status, I do believe that writing personalized contracts is a valuable, healthy way to manage any committed relationship.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.