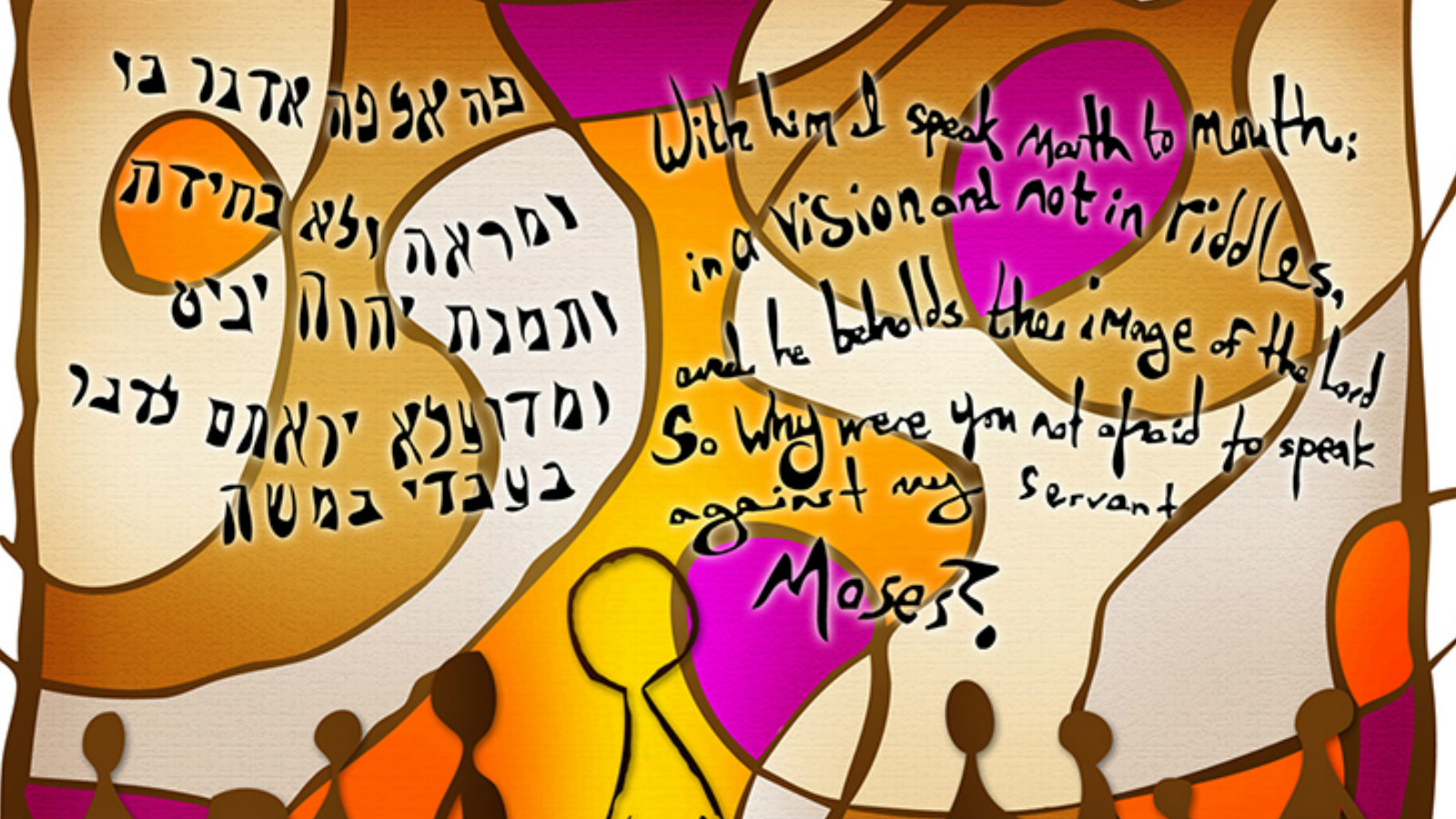

Commentary on Parashat Beha'alotcha, Numbers 8:1-12:16

We often translate d’var torah to mean, “a teaching,” but it literally means, “a word of Torah.” In this d’var torah, let’s examine an actual word, just one: “ruach.” The word ruach in the literal sense means, “wind,” but it also can mean “spirit.” And in this week’s portion, Beha’alotcha, we surprisingly find both meanings, in distinct contexts.

In one instance, we read (Numbers 11:31): “V’ruach nasah mei’eit Adonai,” or ”a wind from the Eternal started up and swept quail from the sea.”

God’s wind blew a flock of birds from the sea upon the Israelites who were encamped in the wilderness. Rather than focus too much on the plot, let’s just examine this instance of the definition of ruach. We’re speaking here about the literal “wind,” the kind that meteorologists discuss. In the biblical context, the wind is a function of God’s will. For the biblical authors, wind was one of the many mysterious items in God’s toolbox. The dominant thought among the ancients was that their own moral behavior was somehow connected to the events beyond their control, including what we now simply call “weather,” whether it was a devastating flood, or, as in this case, a wind sweeping in a flock of birds.

In recent years, wind has ravaged parts of the United States in the form of tornados. When combined with other elements like wind-fueled forest fires and flood waters, immense suffering may ensue. Thus, the kind of Divine wind we find in our portion can be jarring for the modern reader. But the Bible is far from monolithic in conceptualizing God’s use of wind, in relation to humankind. The second example of ruach in our portions is far more palatable for those less inclined toward theodicy. This portion, like many, shows the Israelites doing some major kvetching (complaining). So vociferous is the volume of their ancient “oy gevalt!” that Moses reaches a breaking point in his practice of leadership. He cries out to God:

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Lo uchal anochi l’vadi laseit et kol ha’am hazeh ki kaved mimeini!

I cannot carry this people by myself, for it’s too much for me!V’im kacha at oseh li hargeini nah!

If this is how it is — if this is what you’re doing do me — then just kill me, I beg of you!

Moses faces life and reality, and he sees no way of going on. He is asking — no, begging —God to end his life. And what does God do? First, he instructs Moses to gather together 70 people. Seventy is a fascinating, mystical number, as seven is a symbol of eternity, and 10 is a , or quorum for prayer. Multiply the two and you have a community blessed by the Eternal. In other words, God commands Moses to gather a sacred community. He then instructs him:

Vayeired Adonai be’anan vay’daber eilav vayatzel min ha-RUACH asher alav vayitein al shivim ish hazkeinim.

And God descended in a cloud and, speaking to Moses, God drew upon the spirit of Moses and placed it upon the 70 elders. And when the ruach rested upon them — vayitnab’u (they became prophets), they shared Moses’ burden.

Ruach, in this instance, is not a life-negating circumstance of nature, beyond human control. It’s exactly the opposite. It’s an element that exists within human capacity, which is, at its very core, life-affirming.

Every season brings its own ruach — events that are beyond our control and sometimes utterly devastating. Yet, ruach also means the spiritual wind that gusts within the human soul. Thus, in Hebrew, in Torah, in Judaism, the human being has a role to play in the universe: to affirm the livelihood of the human spirit and, like Moses, share our spiritual burdens with those around us.