The role some Jews played in the Atlantic slave trade, both as traders and as slave owners, has long been acknowledged by historians. But allegations in recent decades that Jews played a disproportionate role in the enslavement of African Americans — and that this fact has been covered up — have made the topic a controversial one.

- Those who make this case include Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam, and David Duke, the former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard.

- A search for “Jews” and “slave trade” on YouTube pulls up more than 50,000 videos, most posted by the Nation of Islam, Duke and their supporters.

- Mainstream scholars for the most part do not accept their conclusions and see the charges as essentially anti-Semitic.

Did Jews really own slaves?

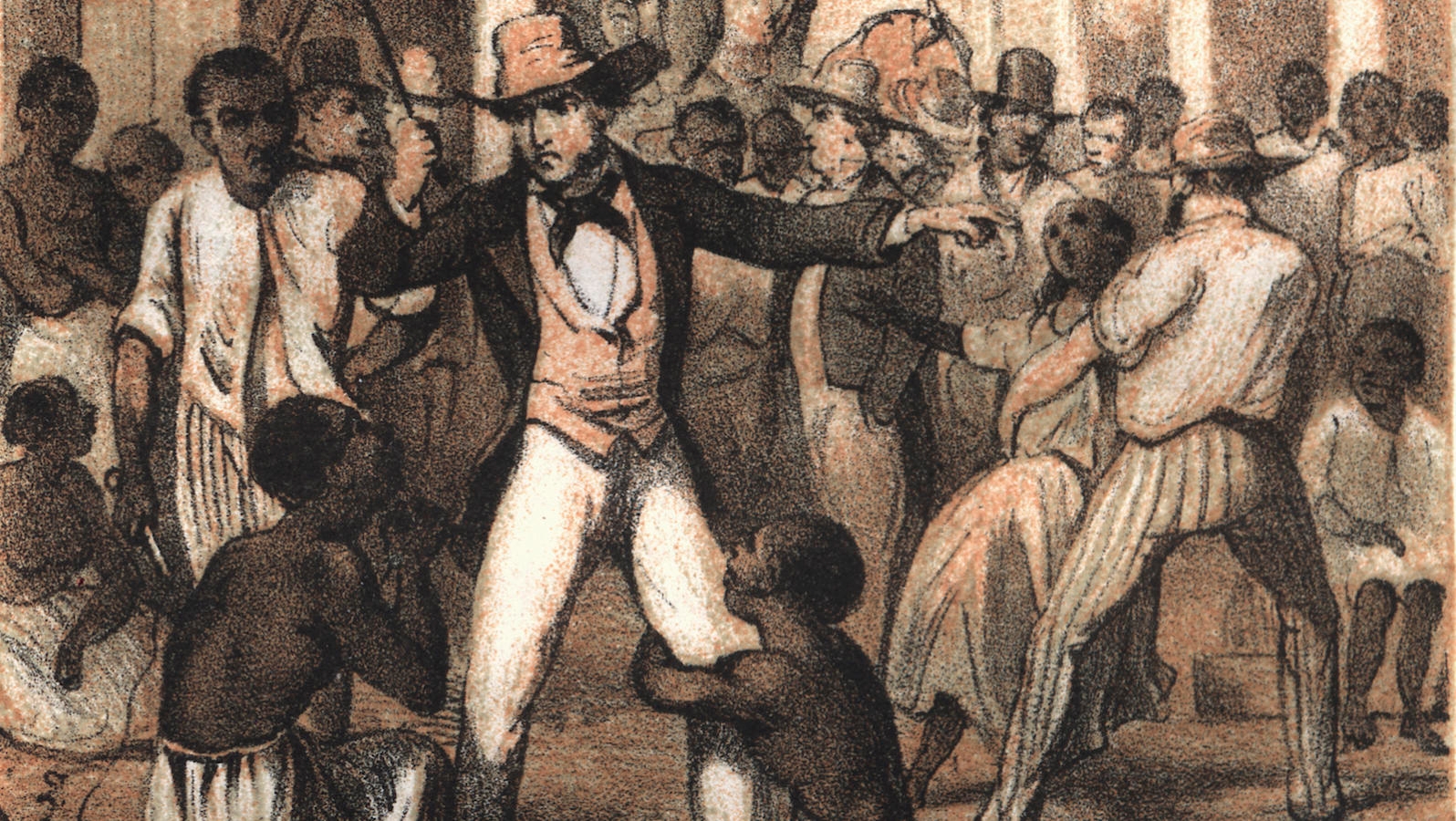

Yes. Jacob Rader Marcus, a historian and Reform rabbi, wrote in his four-volume history of Americans Jews that over 75 percent of Jewish families in Charleston, South Carolina; Richmond, Virginia; and Savannah, Georgia, owned slaves, and nearly 40 percent of Jewish households across the country did. The Jewish population in these cities was quite small, however, so the total number of slaves they owned represented just a small fraction of the total slave population; Eli Faber, a historian at New York City’s John Jay College reported that in 1790, Charleston’s Jews owned a total of 93 slaves, and that “perhaps six Jewish families” lived in Savannah in 1771.

A number of wealthy Jews were also involved in the slave trade in the Americas, some as shipowners who imported slaves and others as agents who resold them. In the United States, Isaac Da Costa of Charleston, David Franks of Philadelphia and Aaron Lopez of Newport, Rhode Island, are among the early American Jews who were prominent in the importation and sale of African slaves. In addition, some Jews were involved in the trade in various European Caribbean colonies. Alexandre Lindo, a French-born Jew who became a wealthy merchant in Jamaica in the late 18th century, was a major seller of slaves on the island.

Did Jews dominate the slave trade?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Not according to scholars that have closely examined the question. Several studies of the Jewish role in the slave trade were conducted in the 1990s. One of them, by John Jay’s Faber, compared available data on Jewish slave ownership and trading activity in British territories in the 18th century to that of the wider population. Faber concludes that the claim of Jewish domination is false and that the Jewish role in slavery was “exceedingly limited.” According to Faber, British Jews were always in the minority of investors in slaving operations and were not known to have been among the primary owners of slave fleets. Faber found that, with few exceptions, Jews were minor figures in brokering the sale of slaves upon their arrival in the Americas, and given the urban-dwelling propensity of most American Jews, few accumulated large rural properties and plantations where slave labor was most concentrated. According to Faber, Jews were more likely than non-Jews to own slaves, but on average they owned fewer of them.

Other studies, by Harold Brackman and Saul Friedman, reached similar conclusions. In a 1994 article in the New York Review of Books, David Brion Davis, an emeritus professor of history at Yale University and author of an award-winning trilogy of books about slavery, noted that Jews were one of countless religious and ethnic groups around the world to participate in the slave trade:

The participants in the Atlantic slave system included Arabs, Berbers, scores of African ethnic groups, Italians, Portuguese, Spaniards, Dutch, Jews, Germans, Swedes, French, English, Danes, white Americans, Native Americans, and even thousands of New World blacks who had been emancipated or were descended from freed slaves but who then became slaveholding farmers or planters themselves.

Davis went on to note that in the American South in 1830 there were “120 Jews among the 45,000 slaveholders owning twenty or more slaves and only twenty Jews among the 12,000 slaveholders owning fifty or more slaves.”

What’s the origin of the Jewish domination claim?

The claim of Jewish domination first came to wide attention with the Nation of Islam’s 1991 book, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Volume One. (Two other volumes would follow, addressing different aspects of black-Jewish relations.) The heavily footnoted and seemingly scholarly book, which lists no individual author and was self-published by the Nation of Islam, purports to present “irrefutable evidence” that Jews owned slaves “disproportionately more than any other ethnic or religious group in New World history.” The book makes a point of basing its findings on Jewish sources, including Encyclopaedia Judaica and multiple works by Marcus, though it includes no data on non-Jewish slave owners and traders from which to establish whether the Jewish role was in fact disproportionate. It also routinely ignores claims from the Jewish sources it relies on that undermine its thesis. (Marcus, for example, asserts that Jews “were always on the periphery” of the slave trade and that “sales of all Jewish traders lumped together did not equal that of the one Gentile firm dominant in the business” — an observation The Secret Relationship ignores.)

Nonetheless, the notion of Jewish domination of slaving was embraced by, among others, David Duke, who has promoted it on Twitter and on his website, and by the City College of New York professor Leonard Jeffries, whose 1991 speech echoing the claim of Jewish domination provoked a public controversy that led to his ouster as chair of the college’s black studies department. (A federal judge later reinstated him.) Tony Martin, a tenured professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley College drew criticism in 1993 for assigning The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews in his courses. Soon after, Martin published a book entitled The Jewish Onslaught: Despatches from the Wellesley Battlefront. Although the book was condemned by Wellesley’s president and many of Martin’s colleagues, Martin remained on the faculty until his retirement in 2007.

More recently, Jackie Walker, a British activist and major supporter of Labor Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, drew criticism in 2016 for claiming in a Facebook post that Jews were the “chief financiers” of the African slave trade. Walker, who also made other public comments offensive to Jews, was briefly suspended from the party because of her claim, but remained unapologetic and was reinstated within a month. (She was later suspended again for publicly bemoaning Jewish centrality in Holocaust commemorations.)

Is there any merit to the book’s claim?

Mainstream scholars have on the whole rejected it. In addition to the study by Faber cited above, refutations have been published by Davis, the Yale professor mentioned above, and Ralph Austen, an emeritus professor of African history at the University of Chicago. Winthrop D. Jordan, a history professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who specialized in slavery, wrote that the book employed shoddy scholarly methods and cherry-picked information, ignoring evidence that modified or countered its pre-ordained conclusion. Henry Louis Gates, director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University called the Nation of Islam’s book “one of the most sophisticated instances of hate literature yet compiled,” and charged that it “massively misrepresents the historical record.”

Is it anti-Semitic to make this claim?

Mainstream scholars and Jewish leaders generally see this claim as anti-Semitic. The Anti-Defamation League, the largest Jewish defense organization, on its website includes “the false claim that Jews controlled the Atlantic slave trade” in its description of contemporary manifestations of anti-Semitism.

As Yale’s Davis noted in his 1994 article, the claim is similar to numerous other historical efforts to blame Jews for a host of problems and atrocities.

Jews, partly because of their remarkable success in a variety of hostile environments, have long been feared as the power behind otherwise inexplicable evils. For many centuries they were the only non-Christian minority in nations dedicated to the Christianization and thus the salvation of the world. Signifying an antithetical Other, individual Jews were homogenized and reified as a “race”—a race responsible for crucifying the Savior, for resisting the dissemination of God’s word, for manipulating kings and world markets, for drinking the blood of Christian children, and, in modern times, for spreading the evils of both capitalism and communistic revolution.

According to Davis, much of the historical evidence that scholars have relied on to document Jewish involvement in the slave trade is itself anti-Semitic, “biased by deliberate Spanish efforts to blame Jewish refugees for fostering Dutch commercial expansion at the expense of Spain.”

“Given this long history of conspiratorial fantasy and collective scapegoating, a selective search for Jewish slave traders becomes inherently anti-Semitic unless one keeps in view the larger context and the very marginal place of Jews in the history of the overall system,” he continued.