Commentary on Parashat Ki Tavo, Deuteronomy 26:1-29:8

How do you know when you’ve come to the end of a journey?

I have tried many times to imagine the moment when my great-grandparents arrived in America. When the ship carrying my great-grandfather entered the New York Harbor, did he already feel that he had arrived? Or did it happen only once his feet touched solid ground? Did he whisper words of gratitude or relief — words uttered, perhaps, in Russian or Yiddish or Hebrew?

This week’s Torah reading begins with the words “when you arrive,” giving the name to the portion “Ki Tavo.” As the Israelites prepare to arrive in the Holy Land after 40 years in the desert, they are given instructions about what they will do to mark their arrival. But these instructions aren’t very clear, and the order seems backward.

At the beginning of Ki Tavo, the people are told to bring the first fruits of the land to the priests, and recite the history of their escape from Egypt and their gratitude to God:

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

You shall take some of every first fruit of the soil, which you harvest from the land that the LORD your God is giving you, put it in a basket and go to the place where the LORD your God will choose to establish His name. (Deut. 26:2)

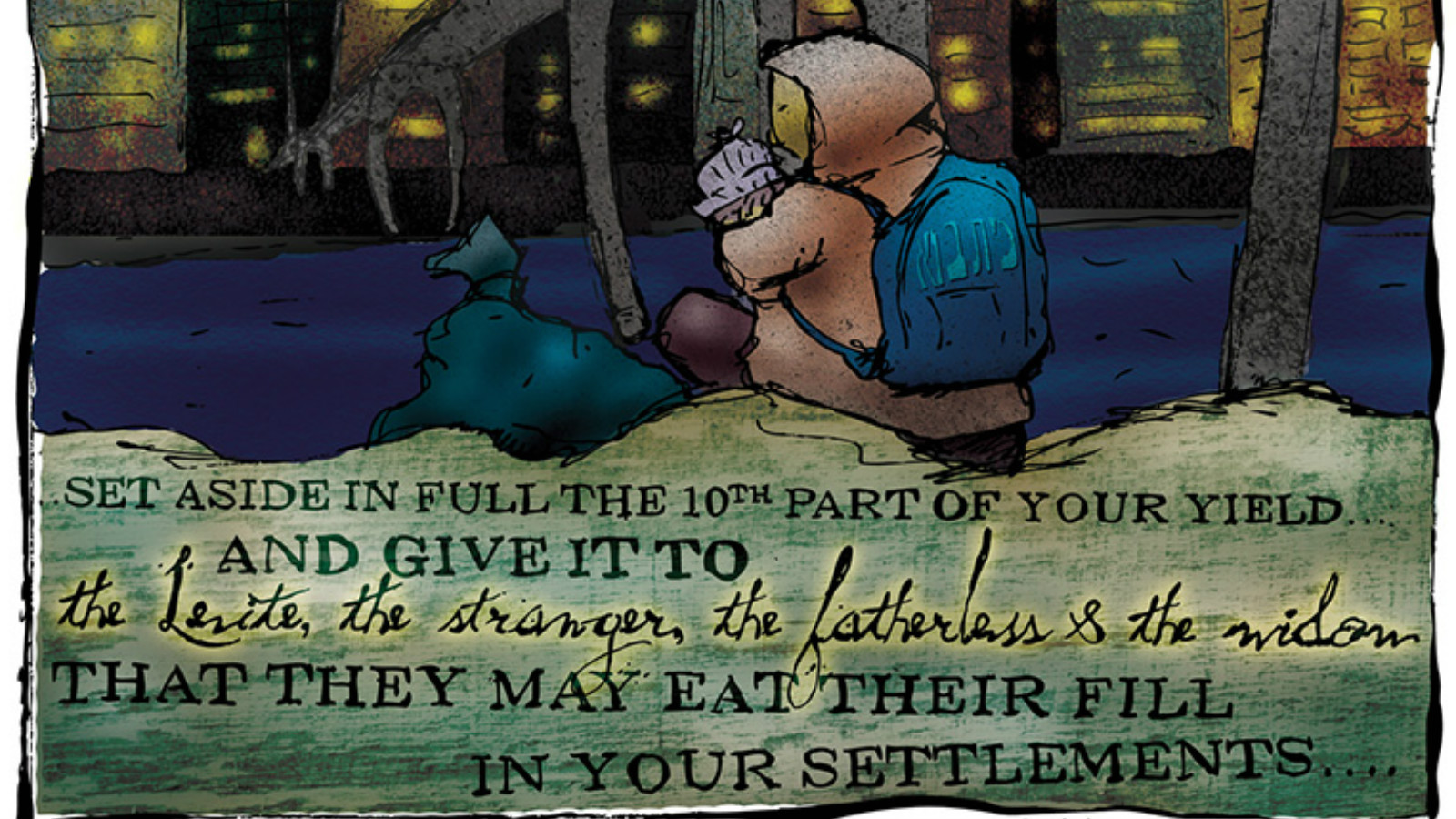

Because first fruits of new trees can take three years to grow, this commandment asks the new arrivals to look far into the future, a future in which they are settled and thriving with produce of their own orchards. In case one might think that the harvest is happening right away, another verse makes it clear: “When you have set aside in full the 10th part of your yield—in the third year, the year of the tithe…” (Deut 26:12), only then do the Israelites get to say “I acknowledge this day before the LORD your God that I have entered the land that the LORD swore to our fathers to assign us.” (Deut 26:3)

But at the beginning of the next chapter, Moses and the elders tell the Israelites: “On the day when you pass over the Jordan into the land that the Lord your God has given you, you will set up large stones and cover them with plaster. You will write on them all the words of this Torah. […] You will build an altar for God of uncarved stones, and you will offer burnt offerings to God. You will sacrifice peace offerings and eat and rejoice in the presence of the Lord your God” (Deuteronomy 27:2-27:7).

In the first moment, the Israelites are told what they will do in the far future; only afterwards do they learn what to do immediately on arrival. On the day of crossing the border, they are to express their gratitude with the things they have on hand — the stones and dirt around them, the animals they bring with them — knowing that in a few years, once they are established, the ceremony will be repeated with the fruits of their investment in the land.

When my great-grandfather looked over the rails and sighted the American coast for the first time, did he immediately begin dreaming about what he might be able to accomplish in the first few years? Or was his first impulse to offer gratitude in whatever way he could in that moment?

Like the Israelites, my great-grandfather was arriving in a place he had only heard stories about. Just as with Canaan, many stories idealized the new land, some were more frightening. But like the Israelites, he set out for the unknown in hopes that the new land would be more fertile.

During my grandfather’s time on the boat, there was plenty of time to dream. But the Israelites, trying to survive in the desert day by day, fighting off attacks by unfriendly kings, didn’t have time to dream. Before they arrived, they needed a vision of what the future would hold.

First fruits. When you arrive in the land, you will bring your first fruits to your leaders, you will retell the story of escape from Egypt, and you will express your gratitude to God, who brought you to a place where the trees are your own, the produce of the trees is your own, the priests are your own, and even the God is your own.

In a moment of great relief, in a moment of recognizing the overwhelming possibilities of a new beginning, it’s natural to recognize the moment itself. But sometimes we need a nudge to look beyond the moment, to dream about what might be once the initial rush of emotion has worn off.

Ki Tavo —when you arrive at the next moment of new beginnings, give yourself the chance to imagine, like the Israelites, what might bear future fruit, and what stories you might one day tell about the journey.