I love words. Part of my initial interest in learning Hebrew was my desire to delve into the Hebrew of our sacred texts, to go ‘deep sea diving’ into the words, seeking meaning and relevance hiding under the obvious. This parsha, detailing the priests’ responsibilities and actions for five varied types of sacrifices, contains minutiae, apparently trivial specifics about a ritual which seem today, without the existence of a priestly class, irrelevant. But, oh, the words!

I want to comment on just two of them.

First, “Tzav,” which is the title of the parsha, is the first word in Leviticus 6:2, and is usually translated as ‘command.’ It is the root of the verb “Mitzvah,” which, in common American conversation, is translated as ‘good deed.’ This translation misses the mark!

When the letter ‘mem’ appears before a verb in Hebrew, it changes that word into a noun—as if the ‘mem’ adds the idea of ‘that which’ performs the action at the root of that verb. For example, the Hebrew verb root “chashav,” to think, was used to invent a new Hebrew word for the computer “machshev,” ”that which thinks.” Thus the word “Mitzvah” therefore means “That which is commanded.”

Digging more deeply, the verb “tsav” also means ‘to connect,’ the way the vav before a word in Hebrew means “and”, thus connecting the previous word with the one having the vav prefix. In ancient Hebrew, the pictographic depiction of a vav was a hook, looking a bit like a crochet hook, indicating a connection. Following this thought process, the word ‘mitzvah’ could more accurately be translated as “a commanded connection.”

In Rabbinic tradition, a mitzvah always requires action, just thinking about a commandment does not fulfill one’s obligation to it. A blessing containing the word ‘mitzvah’ must be followed by the appropriate action. Without that action, the blessing would be considered a “b’racha levatalah” (an unnecessary blessing), being careful not to transgress the grave prohibition of taking God’s name in vain.

Combining these ideas, one derives a more complete translation of the word “mitzvah”: “A commanded opportunity to connect with God through action”! The detailed descriptions of the priests’ responsibilities in this Parsha follow this logic well.

The second word I want to comment upon also appears in verse Lev 6:2, in the phrase “al mokdah al hamizbeach.” “Mokdah” is an Hapax legomenon, a word that only appears once in the Bible in this form; it only refers to the altar-hearth on which burnt offerings were laid and consumed. This word comes from the root “yud kuf dalet” (to be kindled, burnt). Adding the ‘mem’ as a prefix would turn the word into ‘that which is burnt.” But a pyre is not burnt, it is a place where offerings are placed for burning. The phrase reads (in the Jewish Publication Society translation) “The burnt offering itself shall remain where it is burned upon the altar.” The English translation by JPS leaves out the word “mokdah’, which could have easily been translated as ‘altar-hearth.’ When a word in the Bible is not translated, my interest increases.

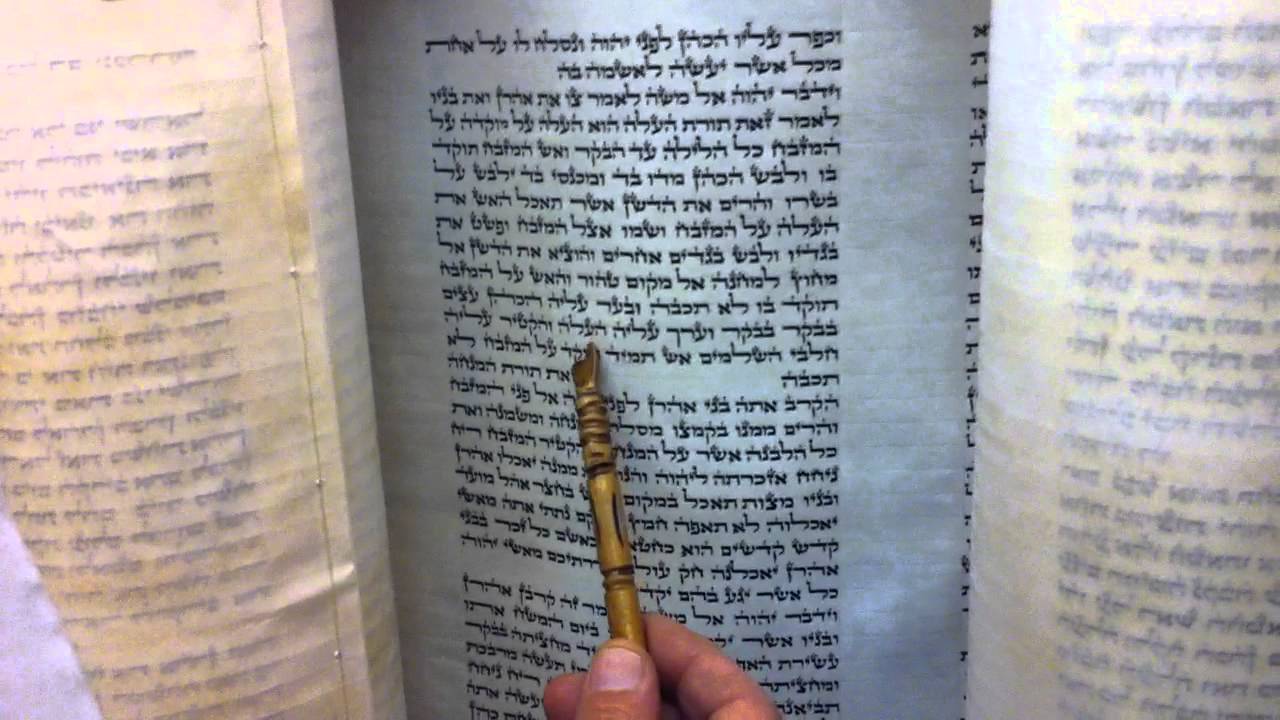

Looking at the way the word actually appears in the Torah scroll, there’s a fascinating surprise. The ‘mem’ is tiny, miniature, inserted and raised above the rest of the word! Why?

I have been taught by Torah scribes that such instances of scribal peculiarities are in fact Midrashim, commentaries on the Biblical text. The Rebbe of Kotzk, commenting on this ‘little mem’, explained that it was there to teach us that the fire in one’s soul should be understated; it should burn within, but show nothing on the outside.

Our own hearts are hearths, the altars upon which spiritual fires can be ignited and kept burning. Even little letters and little words can remind us when we pay close attention. What an apt lesson for this Shabbat, Shabbat HaGadol, the Great Sabbath just before Passover, which ushered in our freedom to fulfill our spiritual destinies.

Shabbat shalom.