By Jewish standards, the question “Why study Torah” is a very new one.

For a couple of millennia, studying Torah was just a given for male Jews. Of course you’d learn it — or at least read it in bite-sized chunks every Shabbat in synagogue, in a never-ending cycle where not only was the yearly reading finished and then immediately begun again on the Simchat Torah festival, but each week’s chunk was trailed on Shabbat afternoon with a little preview of the following week’s portion.

But this is the 21st century, and just because something has been done for millennia by millions of our forebears isn’t reason enough for us to do it any more. So what might be the reasons now?

We’ll need to do a bit of defining first. After all, there are two key words in this question which are not as obvious as they might look – Torah and study.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The word Torah means a multiplicity of things, which in itself might be a cause to study it at least a bit. After all, even if you choose to reject Torah as an important part of your Jewishness, it makes sense to know what it is you are rejecting, if only in outline.

At its simplest, Torah is the text of the first five books of the (Jewish) Bible. But Torah for Jews always meant something more than that. Together with the plain text comes a wealth of commentary, tradition, extensions and challenges which are known as the Oral Torah and can be found in the great rabbinic texts – the Talmud, the Midrash and the still unfolding library of commentary and quest from a vast variety of viewpoints.

Now, study. Many sincere Christians who read the Bible regularly simply sit and contemplate the text. Frequently, such Bible study involves clarification and the addition of information from the historical record that outline the customs of the time or set the narrative in context. In terms of the Jewish Bible, they will pick out those bits that seem most telling for them – a rich story or an important teaching.

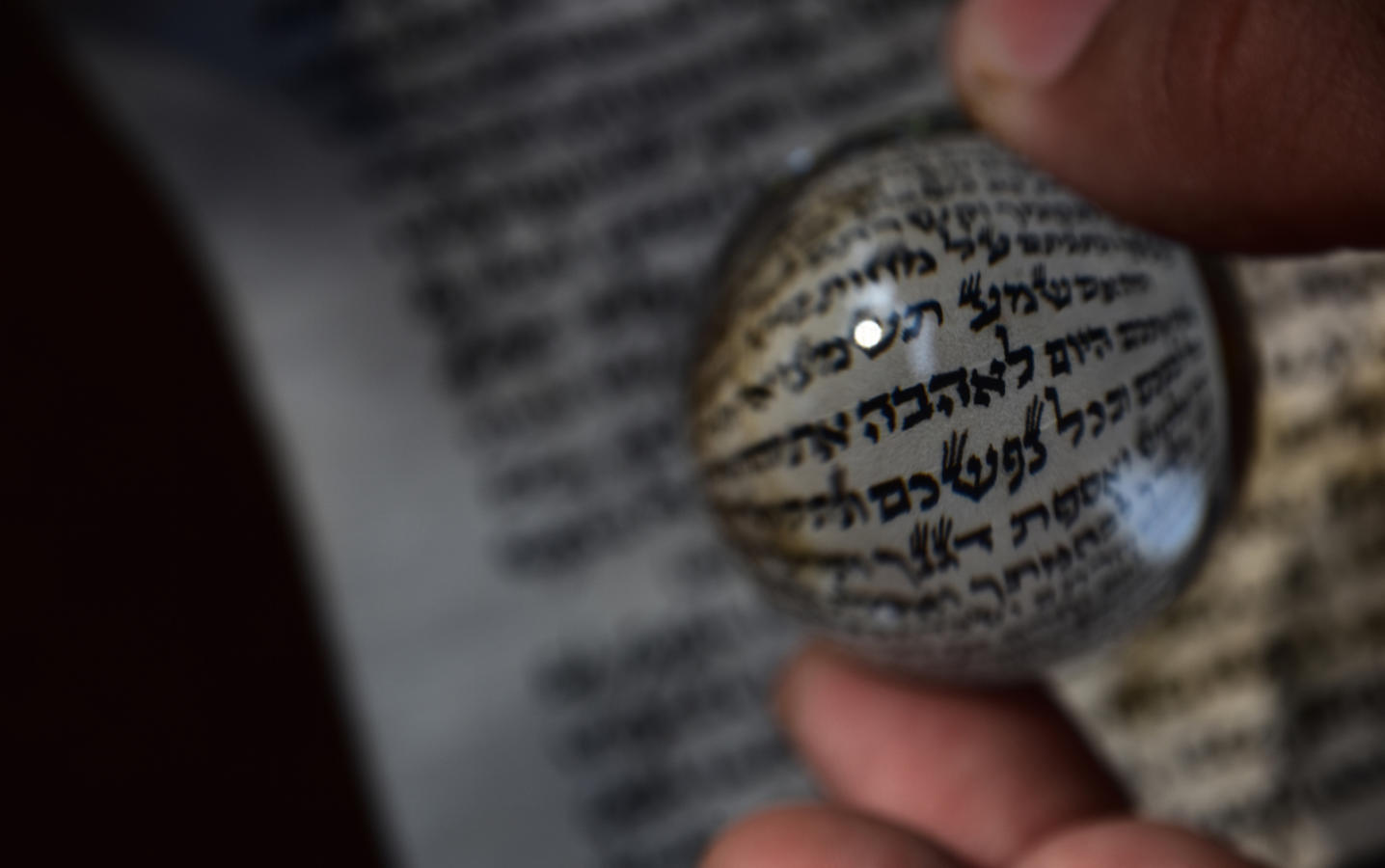

But that’s not the Jewish way. Go into any synagogue of any stripe and look at the Bibles that are used to follow the Torah reading during the service. Pretty well invariably, it will have the Hebrew text, translated into the vernacular as literally as possible, accompanied by a whole host of commentary.

Jews do not read the text bald. The act of reading involves the act of study. Every text of Torah is an invitation to wonder and argument. Torah is never simply obvious. The fundamentalist way is, “If that’s what it says, then that’s what it means.” The Jewish approach has always been, “If that’s what it says, then what does it mean?” Each reading demands an explanation.

This is what is meant by study. By all means, use your own intellectual resources. After all, the Torah belongs to every Jew. But let us also be honest about our own limitations. Do not think that everything you can think is everything that can be thought. The thoughtful Jew, the humble scholar, can stand on the shoulders of giants and use their thinking too.

So study in this sense involves exploration, challenge, questioning, entering into a conversation with the voices of the our past and our global present.

In the end, that’s the how of Torah study. Now to the why.

To be simply utilitarian about it, the mind training involved in teasing out a text, checking the authenticity of our understanding of the translation, and digging as deeply as possible into the implications and consequences of each line has been shown to be of massive intellectual and educational value to students through the ages.

It is not as a result of genetics that Jews have regularly shown themselves to be successful scholars. It’s nurture, not nature. The tradition of Torah study has built up a tradition of questioning and clarifying which is simply an incomparably rich skill to cultivate. It won’t necessarily get you a job, but it might well get you ahead.

But studying Torah gives much more than that. The first book is a magnificently complex record of (often disastrous) human relations. A close study of Genesis will tell you everything you need to know about family dynamics and how to get them wrong. It stretches and challenges our understanding of human responsibility and the order of the world. It goes over and over how spouses might behave toward each other and how siblings, parents and children can mess up – and sometimes come right too.

The remaining four books of the Torah are a close study in how to organize a society. It is not for nothing that the founding fathers of America as well as the early British parliamentarians who challenged the concept of the divine right of kings looked to the “Old” Testament, not the “New,” to find guidance for how a society should be organized.

The demand for Jews to care for the stranger – the most repeated injunction in the whole Torah — has not yet been fully grasped in all its implications by us, let alone the rest of humanity. The laws of inheritance, damages, social responsibility, warfare, property, inclusion, environmental care – you name it, it can be found in the Torah and the commentaries that arise therefrom.

After all that, oddly, the text finds time to digress too. The strange fable of the talking donkey comes out of nowhere and yet gives the Jews our eternal identity as the “people which dwells alone.” We see God himself challenged by a bunch of women and realizes that they’re right and he’ll have to rethink things. We find the apparently unnecessary injunction to “choose life” (doesn’t everyone anyway?) until we reflect on the daily news and find it isn’t so at all.

The Torah asks us to consider miracles — what they are, if they exist, and how they work. It warns us not to trust miracle-makers, and yet 21st century folk are still easily misled. It describes a world in which virtue is not the sole province of the Jews or even of Jewish leaders. The good are sometimes Jewish and sometimes not. And certainly it offers a world where Jews are often backsliding and of poor quality. Even Moses fails a final test. Yet, despite all of this it continues to play an optimistic and upbeat tune.

This essay can only scratch the surface of what there is in Torah which might compel us to study it. But in the end, it boils down to this: Why would you choose to be an ignorant Jew? Surely you owe yourself – and the friends you can study it with – a better fate than that.