The book of Job.

It’s in the Bible, but few of us read it. Because it has no official place in the seasonal cycle of Jewish holiday readings.

So, I have a suggestion. Let’s read it during election season. Every year!

During election season, we reflect on our values. We try to understand how money, family, ethics, and ideology shape our communities. We confront life-threatening issues like global warming and income equality.

These are, of course, the themes of the book of Job.

Job is a good man. A religious man. He’s the father of ten young adults. And he is very, very wealthy.

But he has one very bad day. Raiders steal his livestock and murder his employees. His children die when a tornado destroys their party house. He comes down with a painful, itchy rash. For seven days, he sits in silence, on a pile of dust. Three close friends sit with him.

On the eighth day, Job speaks. He curses his life. Wouldn’t it have been better, he wails, if I had never been born? Because God has treated me badly.

Job explains his anguish. Isn’t there an implied contract? If you are religious, God rewards you. If you are ethical, you merit wealth. But poverty, illness, and grief are punishments. And I didn’t do anything wrong! So, why am I suffering? Tell me, God, which moral and spiritual rules did I break?

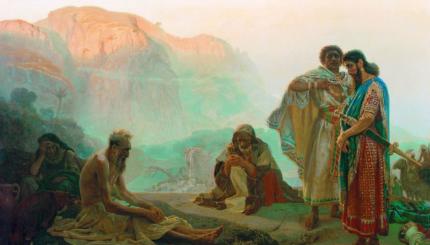

Job’s friends agree with him. Yes, Job, the universe operates by rules of justice. In fact, your kids died for their own crimes. (Hint: do not say this to grieving parents.)

But Job’s friends also disagree. No, Job, God does not owe you an explanation. Obviously, you are being punished. You made yourself a poor, sick, sad, old man. Do the math. Figure out how you sinned and fix it.

The four men argue for hours. But Job still can’t figure it out. Belief in meritocracy used to make sense. Now it only condemns him.

The narrator drops a hint. You can’t buy wisdom with gold. Meaning: Job has only known affluence. He sees from a wealthy man’s perspective. But it’s not the wisdom he needs now.

Of course, Job and friends cannot hear the narrator.

An acquaintance joins the group. A younger man, lesser in social status. And he is angry. All around the world, he says, people are oppressed. Do you think they all blame God? No. They do not. They blame arrogant people.

And we the readers, understand. They blame people like you, Job. Arrogant because you have never known hardship.

But Job still doesn’t get it.

Come on God, he says. Show me what I did wrong!

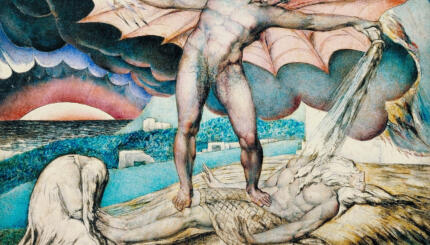

God appears. Oh, Job. Do you really know how the universe works? How the earth was made? Or what keeps the sea within its boundaries? Can you order the right amount of rain to fall? Do you understand the lives of wild animals? When a monstrous force threatens them all, do you know how to tame it?

Oh, says Job. No, I don’t know. Yes, I see that now. I even see you, now, God.

And he changes.

His friends and extended family visit. Their presence comforts him. Job gives his sons and daughters gifts. He sees four generations of grandchildren. He lives a long life and dies contented.

We readers understand. People feel good in Job’s company. Because, now, Job sees people for who they are. Not just rich and poor, winners and losers, givers and takers. And he sees future generations. Their lives matter, too.