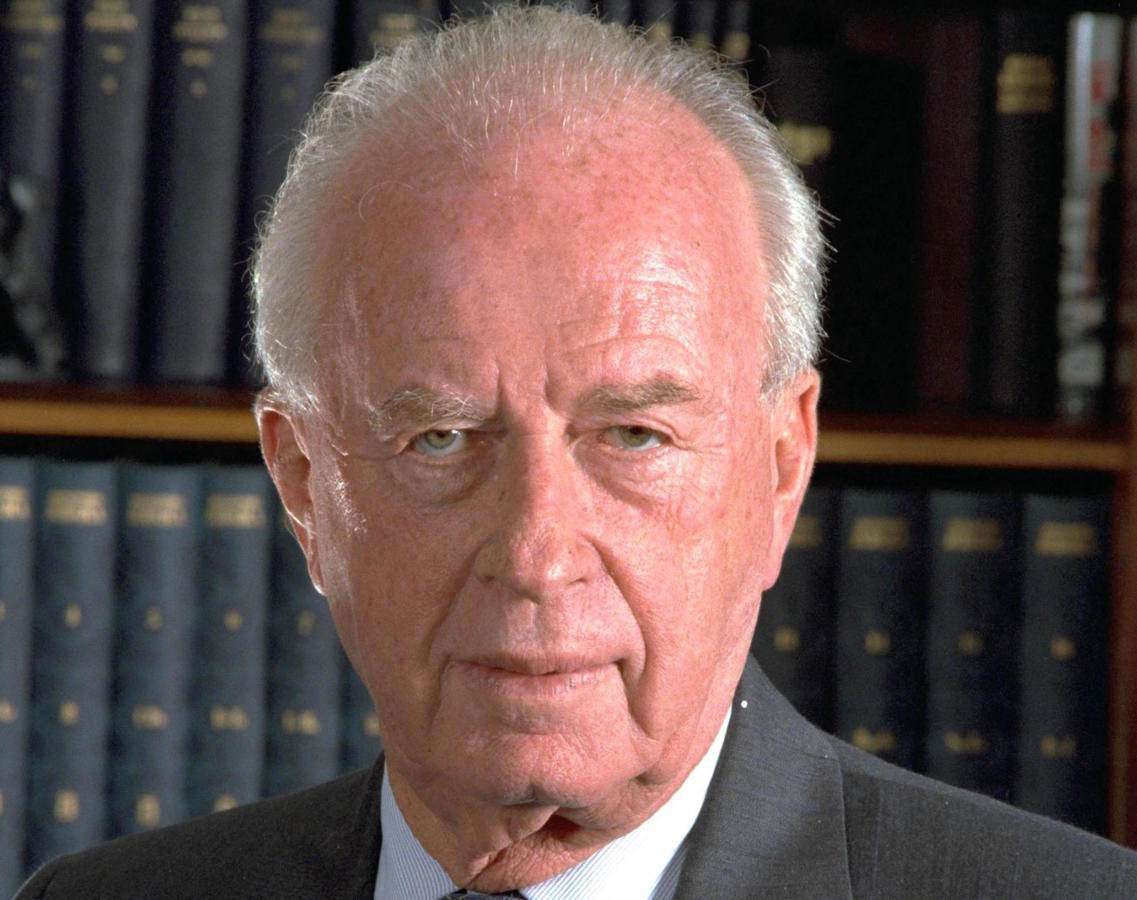

Yitzhak Rabin was an Israeli military hero and political leader who served two terms as prime minister. He was assassinated while in office on November 4, 1995 in Tel Aviv.

A prominent member of the Israeli establishment for more than five decades, Rabin spent his early years of public service building the capacity of the Israel Defense Forces, which he led to a spectacular victory in the 1967 Six-Day War. But while he distinguished himself in his early years as a cunning military man, he is best remembered for enacting perhaps the most consequential shift in the history of Israeli foreign policy: the launch of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process and the signing of the historic Oslo Accords in 1993. The agreement, for which Rabin earned a Nobel Prize but paid with his life, would forever alter the basic terms of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Early Life

Rabin was born in Jerusalem in 1922 to Rosa Cohen and Nehemiah Rubichev, both immigrants from the Russian Empire. The family was poor, but Rabin’s parents were politically connected. When Rabin’s mother died in 1937, David Ben Gurion, the future prime minister, attended her funeral.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Rabin attended the Kadoorie Agricultural High School in the Galilee where he excelled, earning a prize at graduation from the British High Commissioner that would have entitled him to study abroad. Instead, Rabin stayed in Israel and, in 1941, enlisted in the Palmach, a pre-state militia.

Military Career

Rabin rose steadily through the ranks of the military, earning a reputation as an outstanding intellect and a capable thinker in matters of military strategy and operations despite his shyness and social awkwardness. During the 1948 war, he was instrumental in securing the besieged road to Jerusalem. In 1964, he became the Israel Defense Forces chief of staff.

Three years later, with Rabin at the helm of the IDF, the Six-Day War broke out. Israel’s lightning victory in the war and the vast enlargement of its territory helped burnish Rabin’s image as a legendary military figure. But a speech he delivered at Hebrew University seemed to foreshadow the complications of that victory — namely, the occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which Rabin would be compelled to grapple with later as prime minister. “It is possible the Jewish people have never been educated or accustomed to feel the joy of conquest and victory,” Rabin said. “Therefore, it is received with mixed feelings.”

Rabin retired from the army following the war and went to Washington as Israel’s ambassador, a five-year period during which he gained valuable diplomatic experience and an extensive network of connections among American Jews and Washington political figures.

Entering Israeli Politics

Almost immediately upon his return to Israel, he began a career in politics, starting his first stint as prime minister in 1974 — the first native-born Israeli to hold that position.

His tenure began at a difficult moment for Israel. The 1973 Yom Kippur War had caught Israel unawares and the public fallout was significant. The Arab Oil Embargo led to a a quadrupling of global oil prices and an increase in Arab wealth and influence. And Rabin was forced to contend with a fragile parliamentary majority and an increasingly fractious Israeli public.

But Rabin nevertheless managed to achieve an interim agreement with Egypt in 1975, an accord seen as paving the way for the full peace treaty signed in 1979. He also presided over the spectacularly successful rescue of the passengers of a hijacked airplane at the Entebbe airport in Uganda, a mission considered one of the Israeli military’s most legendary feats.

Always an astute strategist, Rabin was already growing concerned about the long-term viability of Israel’s military presence in the West Bank and Gaza. Though he was often careful in his public statements at the time, documents revealed decades later show that he considered Israeli authority there to be untenable and would eventually lead to apartheid. Those views led to increasing conflict with Shimon Peres, Rabin’s longtime political rival, who at the time was sympathetic to the Israeli settler community, an increasingly vocal and potent force in Israeli politics.

Rabin’s tenure ended in disgrace after his wife Leah was prosecuted for maintaining an American bank account in violation of Israeli law. Rabin resigned as Labor Party leader ahead of the 1977 elections and was replaced by Peres, who led the party to a stunning defeat, ending decades of Labor hegemony.

But Rabin stayed in politics, becoming minister of defense under a national unity government in 1984. Three years later, the Palestinian uprising known as the First Intifada began. As defense minister, Rabin ordered the use of force to put down the uprising, which was largely the work of Palestinian civilians. But over time, Rabin came to believe that the Intifada was driven by deeper forces in Israeli-Palestinian relations that could not ultimately be put to rest without a political settlement.

Launch of the Peace Process

In 1992, Rabin was again elected prime minister and he began to translate this belief into actual policy. A secret negotiating channel with the Palestinians led, in 1993, to the signing of the Oslo Accords, a groundbreaking agreement in which Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization recognized one another and promised to negotiate a peace settlement based on the land-for-peace formula. Rabin was visibly uncomfortable shaking the hand of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat at the signing ceremony on the White House lawn, a sign of his ambivalence about the agreement generally and about Arafat particularly.

The Oslo process did not proceed smoothly, though it did pave the way for Rabin’s conclusion of a peace treaty with Jordan in 1994 and the softening of Arab exclusion of Israel from regional economic gatherings. Rabin, Peres and Arafat also shared a Nobel Peace Prize in 1994.

Nevertheless, Rabin’s peace agenda — both on the Palestinian front and with Syria, where he was willing to contemplate withdrawal from the strategically significant Golan Heights in exchange for peace — began to generate significant domestic opposition, fed by a surge in terrorist activity in 1994 and 1995. Rabin was increasingly the target of venomous rhetoric describing him as a traitor and a Nazi. After 22 Israelis were killed in a bus bombing in central Tel Aviv in October, 1994, Benjamin Netanyahu, then the leader of the opposition, went to the site of the attack and accused Rabin of favoring the welfare of the Palestinians over that of Israelis. A number of hardline rabbis suggested that Jewish laws which allow the killing of a Jew who endangers Jewish lives might apply to Rabin.

Assassination and Aftermath

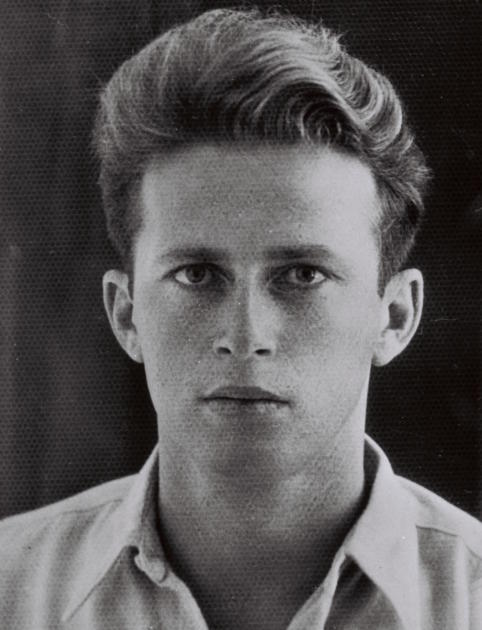

With public support for the peace process in peril, Rabin appeared at a large rally at Kings of Israel Square (later Rabin Square) in Tel Aviv on November 4, 1995. Warning that violence was undermining the foundations of Israeli democracy, Rabin thanked the crowd for demonstrating Israel’s commitment to peace and vowed to persist in his efforts to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. As he departed the stage, a young radical named Yigal Amir fired three shots at him. He was pronounced dead a short while later.

Rabin’s funeral was attended by more than 70 heads of state, including the leaders of Egypt and Jordan. U.S. President Bill Clinton bid an emotional farewell (“Shalom, chaver” — Goodbye, friend) to his partner in Mideast peacemaking. And Rabin’s granddaughter showed the world a softer side of the soldier-statesman.

But the outpouring of goodwill could not halt the shifting political winds. Peres assumed the premiership after Rabin’s death, but ongoing violence led to his narrow loss to Netanyahu in 1996. Rabin’s death ultimately proved to be a watershed moment in Israeli history, inflicting a deep wound on the Israeli peace camp and inaugurating a rightward shift in Israeli politics that has made the prospects of peace with the Palestinians seem more implausible than at any time since Rabin was at the helm.