When you wake up in the morning, how do you feel? Are you like a lion ready to take on the world? Or are you tired and unenthusiastic about the challenges ahead for the day? Or maybe worse, are you bored and feel like you have nothing to look forward to?

I ask not to depress you, but because I have another question: What if every day you awoke feeling like you had an exciting, challenging, world-changing job? And what’s more, it’s a job well within your powers to accomplish?

This is the experience that awaits in the often overlooked part of the morning prayers known as Korbanot.

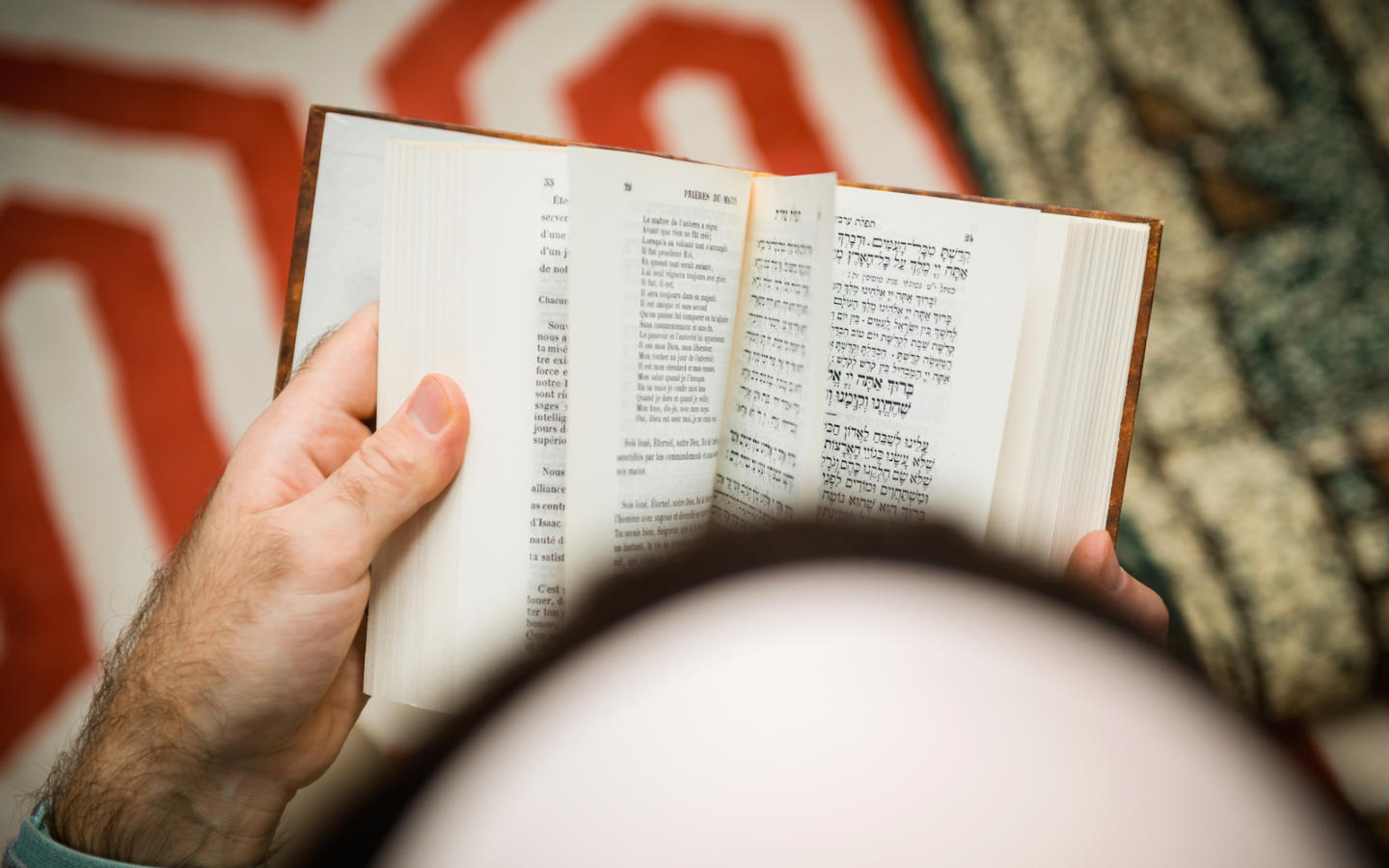

Korbanot (literally “sacrifices”) is tucked away in the no-man’s land of the Jewish prayer book, hidden between the morning blessings and Pesukei d’Zimrah. This section is virtually ignored, even by Jews who pray daily. Children who can recite the morning blessings and the best-known psalms by heart have often never even encountered the Korbanot. Yet Korbanot is all about getting us to feel that we are actually doing something of the utmost importance.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The section begins with a sacrifice that wasn’t even offered: Abraham’s near-sacrifice of his son Isaac. It is impossible to read this paragraph from Genesis without thinking: Wow! Life is scary, and you never know what’s going to happen. While most of us will never experience a divine call to sacrifice our offspring, the story shocks us from the blur we often experience upon waking up.

Once our attention has been captured, the text snatches us out of our slumber with L’olam, a paragraph which first argues that human beings are nothing, no better than any other animal. But it doesn’t stay there long, reminding us that the Jewish people are the ones charged to remind humanity that we have souls, that we have God’s promises, that we can change the world. The paragraph ends with a blessing that essentially blesses God for demanding public sanctification by human beings — not privately, but for the whole world to see.

So the challenge is out there. But can Korbanot help us get there?

Yes, it can. The bulk of Korbanot — and the reason it gets its name — aims to convince us that we are not just plebes and nobodies, but that every one of us can become a High Priest offering the holy tasks performed daily in the ancient Temple. By the time we are done, we have cleaned the altar, washed our hands with the holy waters of the Temple laver, and offered all the daily sacrifices: animal and vegetarian (incense) offerings, voluntary offerings, sin offerings, Passover offerings. A full day’s work.

Korbanot draws from across the Torah, from anywhere the temple priest activities are discussed. But this is not an intellectual game, or a mantra, or even the studying of Torah itself. Our rabbis taught that we recite all these verses in order to actually feel as if we are offering the sacrifices themselves. In fact, our rabbis say – and we actually say it in Korbanot – that if we leave out even one spice from the 11 spices of the incense offered on the gold altar, we are liable for the death penalty.

This is not to scare anyone away, but quite the opposite. When we say these Korbanot we should feel like we are actually the priests. We are needed to perform these rites, and perform them correctly. No one is getting struck down for saying the 11 ingredients in the wrong way, but the more scared you are, the more you feel like the High Priest actually offering the incense. We really do need to see ourselves as priests – all of us, no matter how low and unimportant we feel. For a few minutes, while you are saying Korbanot, you are critical to the success of an elaborate system of holiness that takes up a quarter of the Torah.

Our rabbis assigned all these tasks because they believed we could do them. And every day we say Korbanot we should feel as if we have done them. In five to ten minutes, you will have done a day’s worth of activities that change the spiritual nature of the world. And you are critical to it, especially in this post-Temple period.

Korbanot ends with a Midrash laying out 13 rules of biblical exegesis. The passage puts the complicated system of Torah hermeneutics — how to squeeze obscure philosophical and legal ideas for the verses of the Torah — in our hands. This should be seen as a badge of honor: once we have excelled at our priestly tasks we are worthy of being entrusted with with the entirety of Torah tradition.

The other parts of the daily prayer service are plaintive, praising God’s greatness or petitioning God with our own requests. These have their place. But Korbanot is different. It is about jumping into the holiest, most complicated and most critical work that underpins the daily survival of the entire world. God and our tradition are confident we can do it.

So tomorrow morning, wake up and get to work. Get a prayer book that includes Korbanot and get started on a task that will change the world. After that, you are a High Priest, unleashed and unbound, ready to transform the world around you. Even if the rest of your day is uninspiring, remember that tomorrow morning you are needed for Temple duty. So get up like Abraham and go to work saying your Korbanot: We need you for this holy task!