The earth, like most living things, is primarily comprised of a transparent, odorless, virtually tasteless and colorless fluid we call water. Even though our bodies, the ground, and most of the world we experience seems solid to us, just beneath the surface, water is ever-flowing, moving blood and nutrients and earth, enabling life to grow.

The complete dependence of life on water is powerfully conveyed through the Hebrew root ג-ש-ם (gimel-shin-mem), which can mean both rain and physicality. Lest we forget that we are made up of nearly three-quarters water, the Hebrew reminds us that without geshem (rain), there is no gashmiut (physicality). Or in other words, without mayim (water), there is no chaim (life).

Given the centrality of water to our existence, the prominence of rain and water in the Torah and Jewish liturgy comes as no surprise. In the beginning, God created the world by “separating the waters below from the waters above.” Genesis 1:7 Moses was saved by pharaoh’s daughter, who drew him from the water. Upon seeing Rachel for the first time, Jacob rolled the stone from the mouth of the well and offered her flock water. Genesis 20:10 Our path to freedom from slavery in Egypt went directly through water. The priests in the ancient temple sanctified themselves with water. Prayer, we are told in the Book of Lamentations, involves pouring out our hearts like water. Lamentations 2:19

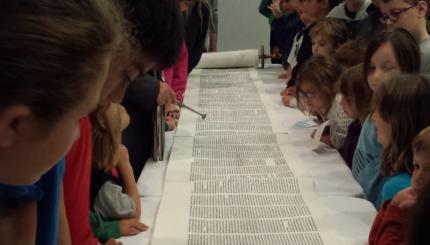

Tefillat Geshem, the prayer for rain that Ashkenazi Jews recite on Shemini Atzeret, recalls many of these transformative encounters with water. (Sephardic Jews recite a different prayer for rain, Tikkun Hageshem, on Shemini Atzeret.) Recited at the conclusion of the festival of Sukkot and at the traditional start of the rainy season in Israel, the prayer calls upon God to remember the righteousness of our ancestors and to grace us with the gift of flowing water. “For their sake, do not withhold water,” we recite. “For the sake of their righteousness, grant the gift of flowing water.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

For the full text of Tefillat Geshem in Hebrew, click here.

Through detailing the many and varied ways that water has played a central role in the defining moments of our ancestors, Tefillat Geshem encourages each of us to consider the defining moments that water plays in our own lives. The imagery of the poem describes birth and death, trials and triumphs, vulnerability and strength, scarcity and abundance — all of which seems to suggest that we too are part of this story, part of the cycle of water, the cycle of life.

Water is always in movement. Since the beginning of creation, it has continuously been flowing in an endless cycle with no beginning and no end, from evaporation to condensation to precipitation to infiltration and back to evaporation. And this cycle is a closed cycle; the rain falling outside the window right now is made of molecules that existed when Abraham and Sarah walked the earth.

It is the movement of water, the flow, that supports life. The soil beneath our feet may be rich and fertile, but without water a plant can’t take up the nutrients it needs to survive. And when plants take up water and nutrients from their roots, they must also release water from their leaves. Absorbing and releasing, receiving and giving, this is the miraculous cycle that has happened every second for millions of years.

We too are part of this flow. From Abraham and Sarah to all of us, the water flowing through us is part of an unbroken chain, a cycle of water that continues to move and nourish and support life. Which is why we invoke the merits of our ancestors when we recite Tefillat Geshem and pray that this same water continues to flow for us, for our children, for all of creation — for blessing, for life and for abundance.

“For you are Hashem our God,” the prayer concludes. “Who causes the wind to blow and the rain to fall. May it fall as a blessing and not as a curse. May it be for life and not for death. May it bring abundance and not famine.”