In the 26th chapter of the Book of Jeremiah, we read:

It was the LORD who sent me to prophesy against this House and this city all the words you heard. Therefore mend your ways and your acts, and heed the LORD your God, that the LORD may renounce the punishment He has decreed for you. As for me, I am in your hands: do to me what seems good and right to you. But know that if you put me to death, you and this city and its inhabitants will be guilty of shedding the blood of an innocent man. For in truth the LORD has sent me to you, to speak all these words to you. Jeremiah 26: 12-15

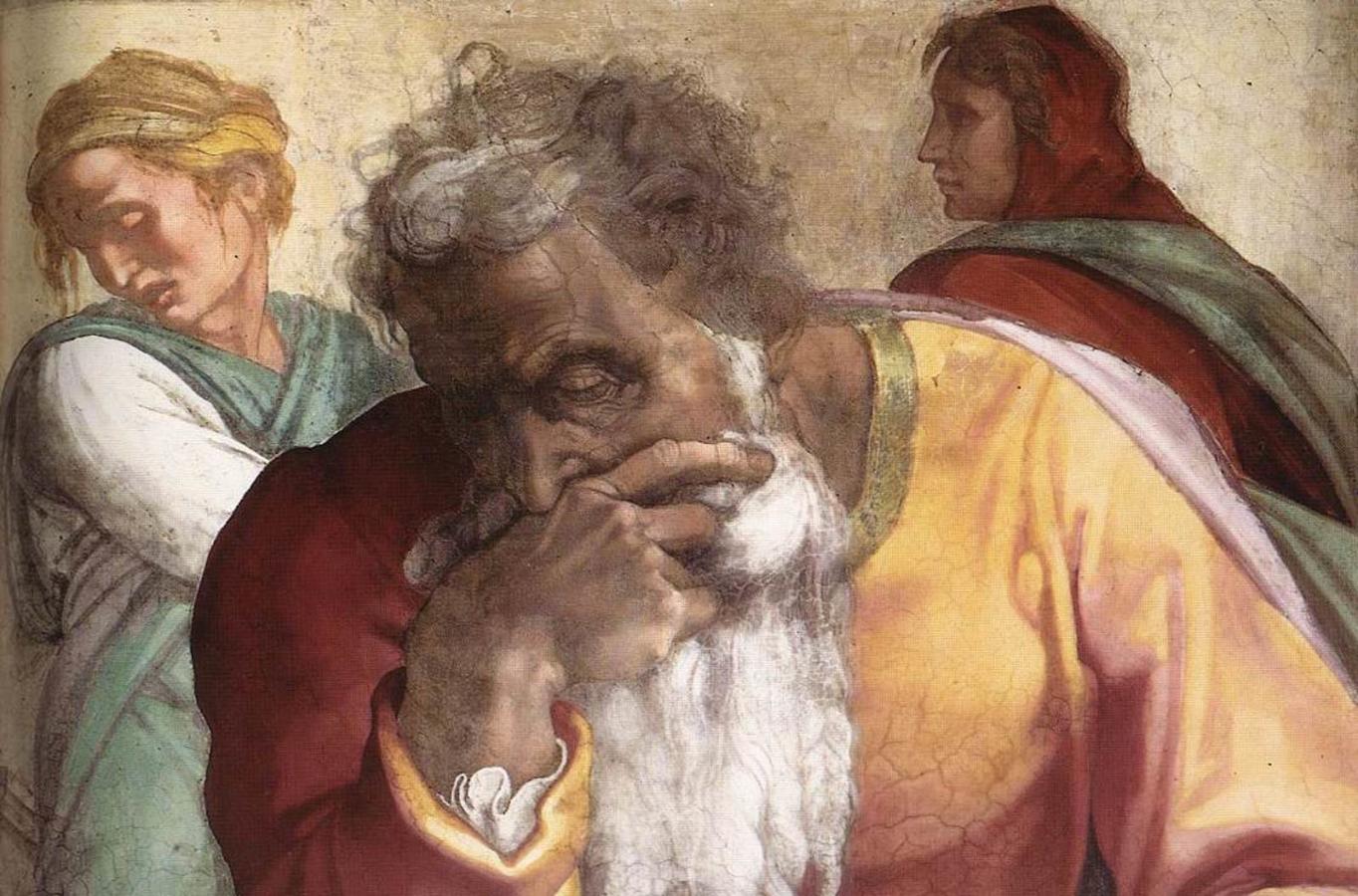

The prophet Jeremiah lived at an agonizing time in the history of ancient Israel. Since its inception, tiny Israel always seemed to be caught between the superpowers of the north and the south. The overrun of the country by the Assyrians in 721 BCE had erased the ten tribes of northern Israel from history — a national calamity still very much on the minds of Jeremiah and his compatriots when, in 605 BCE, Babylonia, another empire from the north, arose and vanquished its rival to the south, Egypt, in the epic battle of Carchemish.

For some time already, Jeremiah had been warning against making alliances with Egypt and he saw the Babylonian invasion not only as inevitable, but as the express will of God. Jeremiah predicts that servitude to Babylon will last 70 years — a message of doom that, unsurprisingly, does not go over well with the political establishment.

According to the biblical account, the priests and prophets rise up against Jeremiah, and when the palace officials arrive on the scene they demand the death penalty for Jeremiah. But Jeremiah persists in his agitation, railing against what today we would call both domestic policy (inequality and injustice) and foreign policy (unholy alliances).

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Eventually he is forced into hiding and later arrested and imprisoned. During this time, the prophet dictates his pronouncements so that his disciple Baruch can read them from a scroll even if he is silenced. But he also takes another dramatic step to ensure that the other half of his message—that God will not forsake Israel forever—will not be ignored: He buys a piece of land in his home village of Anathoth.

At the time, Anathoth was likely already under enemy control. Buying land there, in the words of one prominent commentator, “must have seemed like sheer madness.” At a time when Jeremiah himself was preaching that the Babylonians would capture Jerusalem, destroy the country and exile its population, buying land in territory under Babylonian control makes no sense.

Yet Jeremiah goes through the procedure of securing and preserving the deed and ensuring that the public knows about it. He grasps that he has been given a way to dramatize that the exile of his people will not last forever—that God’s turn away is not a sign of forsaken love for all time.

Unwavering hope is as much as a part of Jeremiah’s message as rebuke. To Jeremiah and the classical prophets, no one could be shielded from the harsh reality of God’s judgment, but neither would anyone be denied the consolation of God’s ultimate love — nor the hope that comes from that knowledge.

At one point, Jeremiah uses the unique expression “hope of Israel” to refer to God. As he did when he purchased his ancestral land, Jeremiah repeatedly speaks about the coming restoration of Israel’s fortunes. In fact, one of his best known declarations is repeated at Jewish weddings to this day: “Again there shall be heard in the towns of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem the sound of mirth and gladness, the voice of groom and bride … for I will restore the fortunes of the land as of old—said the Lord.” (Jer. 31:10-11)

Jeremiah dies in obscurity in Egypt, but his ideas endured. The prophetic message of hope Jeremiah instills is echoed to a degree by almost all the later prophets.

Ezekiel’s famous vision of the dry bones, in which a valley full of bones come back to life, is a classic prophetic statement of hope, symbolizing the restoration of the people and the land of Israel. Amos declares that the Jews who return to their land will be never be uprooted again. Hosea affirms: “In that day … I will banish bow, sword, and war from the land.” Micah perhaps put it most memorably when he says, “And they shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not take up sword against nation; they shall never again know war.”

These words of comfort and hope from the age of classical prophecy took deep hold in the Jewish psyche. To this day, we use the term jeremiad to mean a cautionary or angry harangue. And indeed, sometimes when he preached, Jeremiah was angry. But at other times he delivered words of comfort and hope that are second to none among the prophets in their eloquence.

The LORD revealed Himself to me of old. Eternal love I conceived for you then; Therefore I continue My grace to you. I will build you firmly again, O Maiden Israel! Again you shall take up your timbrels And go forth to the rhythm of the dancers. Again you shall plant vineyards On the hills of Samaria; Men shall plant and live to enjoy them. Jeremiah 31: 3-5

An ancient midrashic text stipulates that there are three types of prophets: those who insist on the honor due the father (God), those who insist on the honor due the son (the people), and those who insist on both. Jeremiah is cited as a prophet of the latter kind, his prophetic moment a statement of faith in God and in the future of his people.

Adapted from Path of the Prophets (JPS, 2018) by Rabbi Barry L. Schwartz