Kinot are religious poems written to memorialize the tragedies that befell the Jewish people on Tisha B’Av, the midsummer fast day that commemorates the destruction of both ancient Temples in Jerusalem. Kinot (singular: kinah) draw on the biblical imagery of the destruction of Jewish sovereignty as well as later disasters.

The word kinah is already found in the Bible, where it indicates an elegy or lament (Ezekiel 19:1 and Amos 5:1). In rabbinic times, the term kinah was associated with mourning practices. At burials, kinot would be sung to pull at the heartstrings of those who suffered a loss Mishnah Moed Kattan 3:9. According to one teaching, even poor people could not be denied a singer of dirges at their funeral. Mishnah Ketubot 4:4

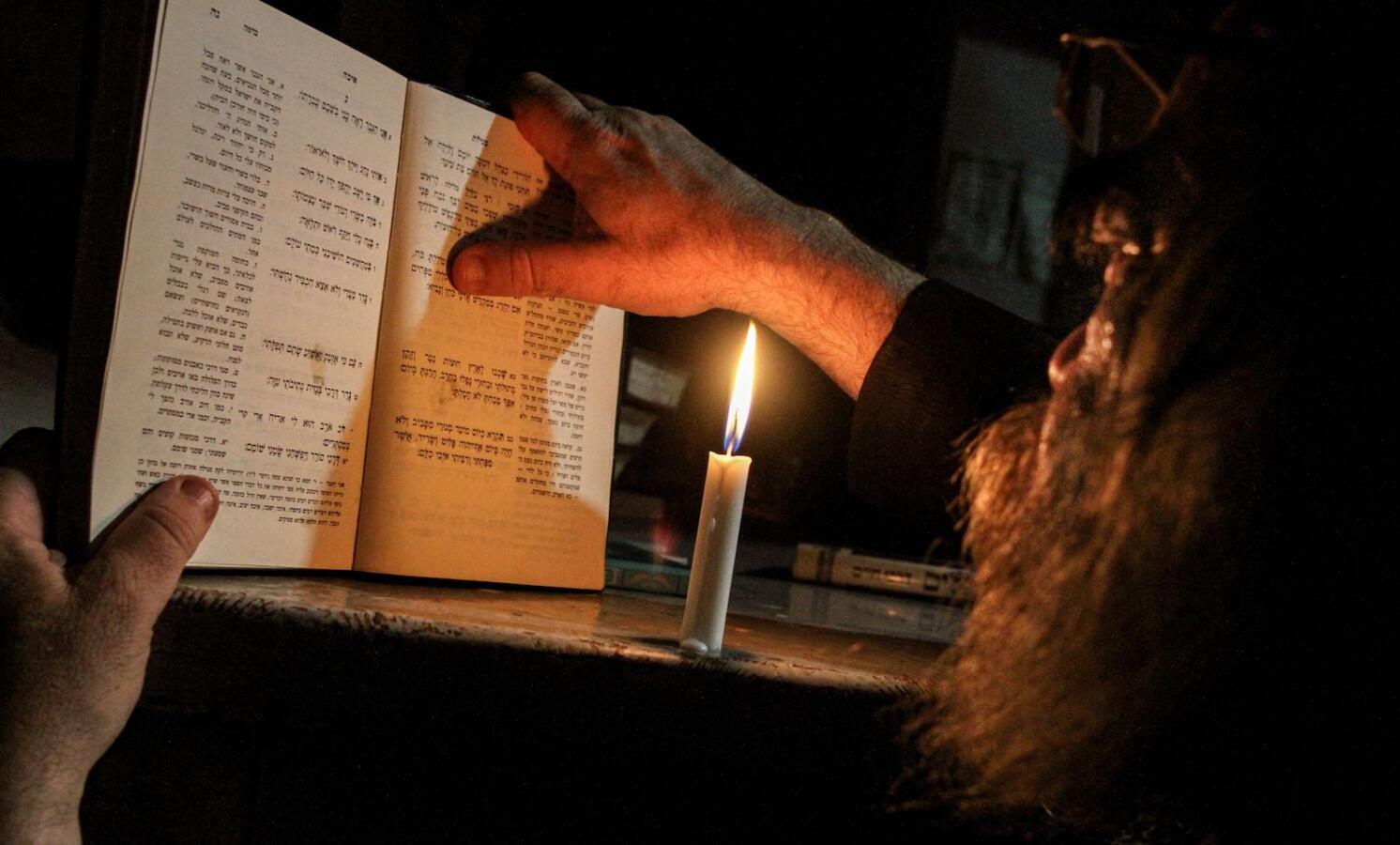

On Tisha B’Av, we are all mourners, and we all join together in the recitation of communal laments. In fact, Eicha, the biblical book we read in synagogue on the holiday, was originally called Sefer Kinot, a fact that is reflected in its English name: the Book of Lamentations. The purpose of reciting Eicha was to “arouse one’s heart to mourn,” according to one rabbinic teaching.

But apparently Eicha wasn’t enough. Toward the end of the talmudic period, poets began writing special pieces for Tisha B’Av. The scholar E. Daniel Goldschmidt claims that originally the poems were added into the middle of the Amidah prayer, in the blessing about rebuilding Jerusalem. Some time later, the poems shifted to later in the service, after the special Torah reading for Tisha B’Av. That spot in the service was expansive, and the number of poems grew. It is not uncommon for some communities to recite 40 or more kinot during the Tish’a B’av morning service. Later still, the kinot’s effectiveness and popularity led them to be included in the nighttime service for Tisha B’Av as well, following the reading of Eicha.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The first known poet to write kinot was Eleazar Ha-Kallir, the finest creative literary mind of 6th-century Palestine. Kallir drew on hundreds of midrashim and biblical verses to craft poems that abound in allusions. A single line might include multiple references to rabbinic legends and images, all while fitting a rhyme and/or meter.

One example of Kallir’s brilliance is the kinah Im Tochalna Nashim Piryam, an elegy to merciful women who, in the crisis of the Temple’s destruction, ended up turning on their children instead of protecting them. An alphabetical acrostic, each line draws upon a verse from Eicha or, more often, a midrash based on its verses. The lines are followed by a refrain: Allelai Li (“I cried out”), a quote from the Book of Job.

In one line, Kallir deftly describes a trick played on Jewish refugees who had escaped from Jerusalem. Originally detailed in the Jerusalem Talmud, the story concerns 80,000 young priests who sought shelter with the descendants of Abraham’s son Ishmael. They asked for water, but their hosts gave them salty foods. Then they brought out water skins, but instead of refreshing liquid, there was nothing but hot air inside. Thinking they were going to taste water, the priests were tricked into ingesting the air, distending their bellies and killing them. Kallir memorializes this story in the line: “When their breath burned from salty foods and blown up skins, I cried out.”

This is just one of 22 tragedies recounted line by line in this kinah, one of 50 Kallir wrote for Tisha B’Av.

Following Kallir, dozens of poets wrote kinot that covered a wide range of tragic subjects: the destruction of the first and second Temples, the experience of exile, the death of prominent rabbis, and the rituals of the bygone Temple period. But many poems also focused on the sins of Israel as a cause of this suffering, although some end with a plea for redemption because the suffering far outweighed any deserved punishment. A particularly popular story that found its way into the poems was the death of Zecharia ben Yehoyada, a biblical priest and prophet who fell victim to internal Jewish strife. Much later suffering stemmed from the Jewish people turning a blind eye to this murder.

During the Middle Ages, the number of kinot continued to grow. Many dealt with more contemporary tragedies: Jewish deaths during the Crusades, the burning of the Talmud in Paris in 1242 and, in the last century, the Holocaust. The series of kinot ends with poems longing for Zion, including Yehuda HaLevi’s poem Tzion Halo Tish’ali. In many traditions, the final poem in the kinot series is Eli Zion, which first appeared in the 14th century and yearns for a rebuilt Zion.