Viddui is a confessional prayer whose recitation is one of the core requirements of Yom Kippur. The term itself means confession, but it actually encompasses much more. Viddui comes from the same Hebrew root as the words for thank, acknowledge and admit. Some believe that this root – ידה – is even connected to the Hebrew word for hand, suggesting that the act of confession entails standing open-handed, prepared to give of ourselves and admit what we have done.

The idea of confessing a sin appears in the Bible. In Numbers 5:6-7 we read: “A man or woman who does a sin toward a person, thus breaking faith with God, and that person realizes his guilt, he shall confess the wrong that he has done.” Later rabbinic sources understood this to entail a requirement to confess on one’s deathbed, which is why we have a tradition of reciting Viddui as a person is dying. Perhaps this is also why it is so prominent in the liturgy of Yom Kippur, a day in which we try to change our life by rehearsing our own death, abstaining from life-affirming activities like eating and having sexual relations.

The commandment to confess on Yom Kippur is part of the oldest layer of Jewish law. In the Tosefta (Kippurim 4:14), we read that one must confess before the start of the final meal prior to Yom Kippur. But this is not a one-time act. One has to confess after the meal as well, lest one sinned during the meal. In fact, one continues to confess during every service of Yom Kippur, five more times in total, lest one sin during the day of Yom Kippur itself. This may be a grim view of human nature – we can’t even go a few hours without sinning! – but perhaps a realistic one.

What does one say to confess? There are different traditions about this, and many rabbis had their own versions, as detailed in the Talmud. But one very short phrase is essential: Aval anachnu hatanu. In truth, we have sinned.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

This is stark in its brevity: An admission that we have sinned is the essence of confession. But what is the function of the word aval – “in truth”? After all, simply saying “we have sinned” would seem to suffice.

The word aval is relatively rare, coming only 11 times in the Bible. Unlike in modern and rabbinic Hebrew, where it means “however,” it originally meant “in truth.” Its inclusion in Viddui appears intended to draw our attention to the only time it is used in the Bible in the context of an admission of guilt — the confession of Joseph’s brothers.

In Genesis, we read of the brothers throwing Joseph into a pit and then later selling him into slavery, essentially committing the sin of kidnapping (if not fratricide). Later in the story, we hear them admit their guilt, unwittingly, to Joseph, who is listening in: “They said to one another: In truth, we are guilty on account of our brother, because we looked on at his anguish, yet paid no heed as he pleaded with us. That is why this distress has come upon us.” Genesis 42:21

The essential confession of Yom Kippur is therefore built on the confession of Joseph’s brothers, who finally admit that Joseph suffered and they ignored his pleas. This is the core sin that lies at the center of confession: brothers harming one of their own. This sin also gets prominent placement in a later section of the Yom Kippur service, the Ten Martyrs, the recounting of the gruesome killings of ten rabbis of the mishnaic period who, we are told in the midrash, were led to their deaths to pay for the sin of Joseph’s brothers. (Midrash Eleh Ezkereh, Beit ha-midrasch vol 2, pp. 64-65).

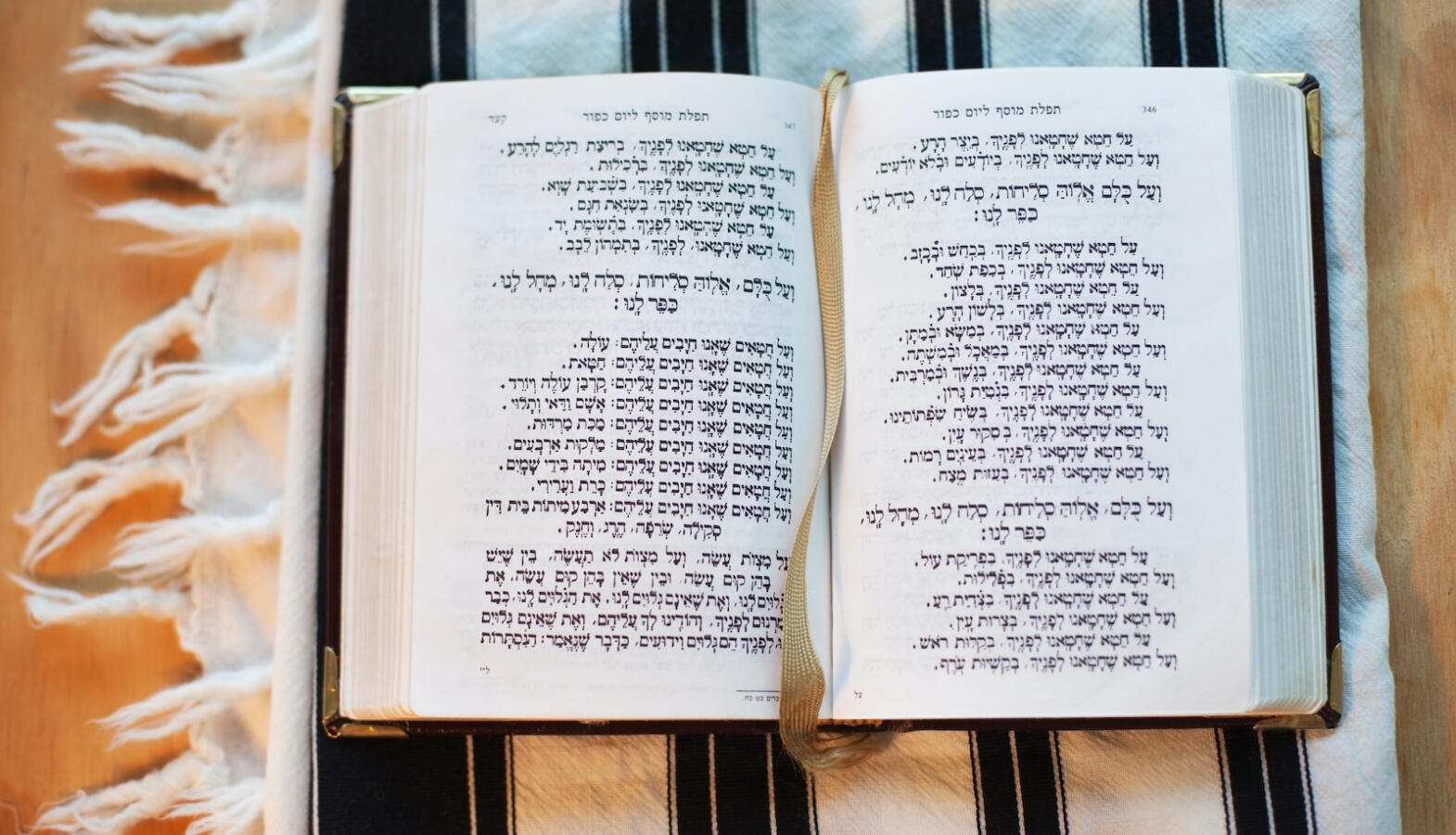

Over time, the formula that constituted the confession grew from this kernel to a longer alphabetical acrostic — and now two alphabetical acrostics: the Ashamnu series and the Al Chets. This stylized confession, recited during each Amidah of Yom Kippur while gently striking the chest, is a litany of categories of wrongdoing that is meant to cover the entire congregations’ sins.

Nowadays, these scripted confessions often serve as a substitute for the real work of confessing one’s own particular sins. But it wasn’t obvious to the rabbis that confessing specific, personal sins was ideal. Indeed, the great talmudic sage Rabbi Akiva was opposed to listing specific sins, creatively rereading a verse in Psalms 32:1 to mean that people are praised for covering up their sins. Perhaps detailed personal confession is not a religious ideal and risks cultivating an unhealthy attitude of extreme guilt.

Should one have to confess sins previously admitted to? This is also debated in the Talmud. Although one rabbi says one should always confess a sin, even from previous years, the majority opinion states that one should not repeat a confession year after year. One can go overboard with admitting guilt, and there is value in stating one’s sins and moving on without forever dwelling in the past.

Are there any sins that are not entirely our fault even though we committed them? Rabbi Akiva offers a take on that question as well, even pointing a finger at God in an attempt to shift full blame away from the Jewish people. In considering the sin of the Golden Calf, one of the core sins recalled on Yom Kippur, Rabbi Akiva makes a daring claim: God set us up to fail. By giving the Israelites so much gold when they left Egypt, God created the factors which led to the sin of the Golden Calf. Rabbi Akiva even imagines God confessing: “I gave them too much gold.” Perhaps even the worst sins are not entirely our fault.