While the ink dried on the parchment of the Torah scroll long ago, the Torah itself is alive and ever-changing, its ancient narratives constantly renewed in each generation.

This idea is encoded in the two blessings that bracket each aliyah, the subsection of the weekly Torah portion chanted each Shabbat in the synagogue. Both blessings end with the same line: Blessed are you, God, giver of Torah. The second blessing reads in its entirety:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעולָם אֲשֶׁר נָתַן לָנוּ תּורַת אֱמֶת וְחַיֵּי עולָם נָטַע בְּתוכֵנוּ. בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ נותֵן הַתּורָה

Blessed are you God, ruler of the universe, who gave us the Torah of truth and planted within us eternal life. Blessed are you, God, Giver of Torah.

The use of the word nata, planted, harkens back to Genesis, when God plants a garden in Eden and places an etz chaim, a tree of life, at its center. Tree of life is a common metaphor for Torah used throughout Jewish literature. The ancient rabbinic work known as Avot d’Rabbi Natan includes the Torah as well as the tree among the ten entities that are truly alive, a list that includes water, the land of Israel and God. The Talmud in Chagigah 3b explains that just as a plant flourishes and multiplies, so do matters of Torah flourish and multiply.

The structure of the blessing also suggests a parallel between “Torah of truth” and “eternal life.” The medieval rabbi Jacob ben Asher, commonly known as the Tur, explains the parallel in this way: Torah of truth refers to the Written Torah, while “eternal life” refers to the Oral Torah.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

If we understand the Oral Torah to include not only the ancient works of the Mishnah and the Talmud, but any interpretive act of Torah — including those of our present day — this notion of Torah as the giver of eternal life takes on a poignant resonance. Our understandings and interpretations of the written text of Torah are drawn from an eternal well. By necessity, each generation reads the words of the Written Torah through the lens of its own experience. This is true not only from one generation to the next, from one community to another, but even for each person over the course of a lifetime.

A hint of this idea is found in the final words of both blessings, which describe God as the “giver of Torah.” The Hebrew word noten is a present-tense verb. The Torah isn’t something that was given once millennia ago. God is always giving Torah — giving us the opportunity to make Torah alive.

Why do we read the same words of Torah year after year? Because every year we see these words anew – not because we try to, but because each of us is alive and constantly changing. Every time we chant Torah, we hear the old narratives with new vision and new perspective. We breathe life into them, as God breathes life into us.

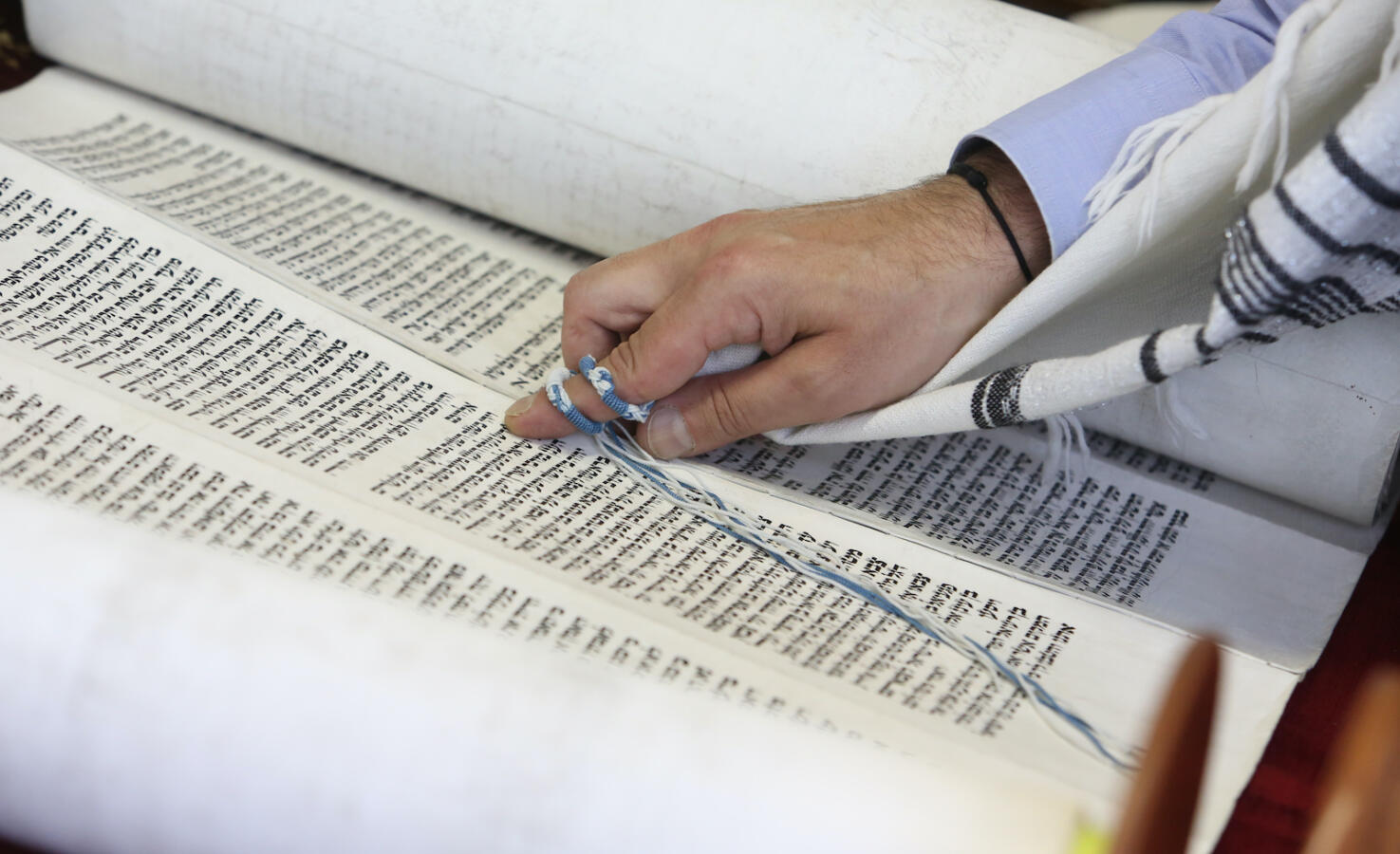

In this sense, the written Torah scroll isn’t an artifact preserved behind protective glass. It’s opened, exposed to the elements, read from out loud and learned from anew in every generation. The Torah is a torat emet, a teaching of truth — always true to our experience, always reflected in our lives and our lives in it, eternally alive and relevant.