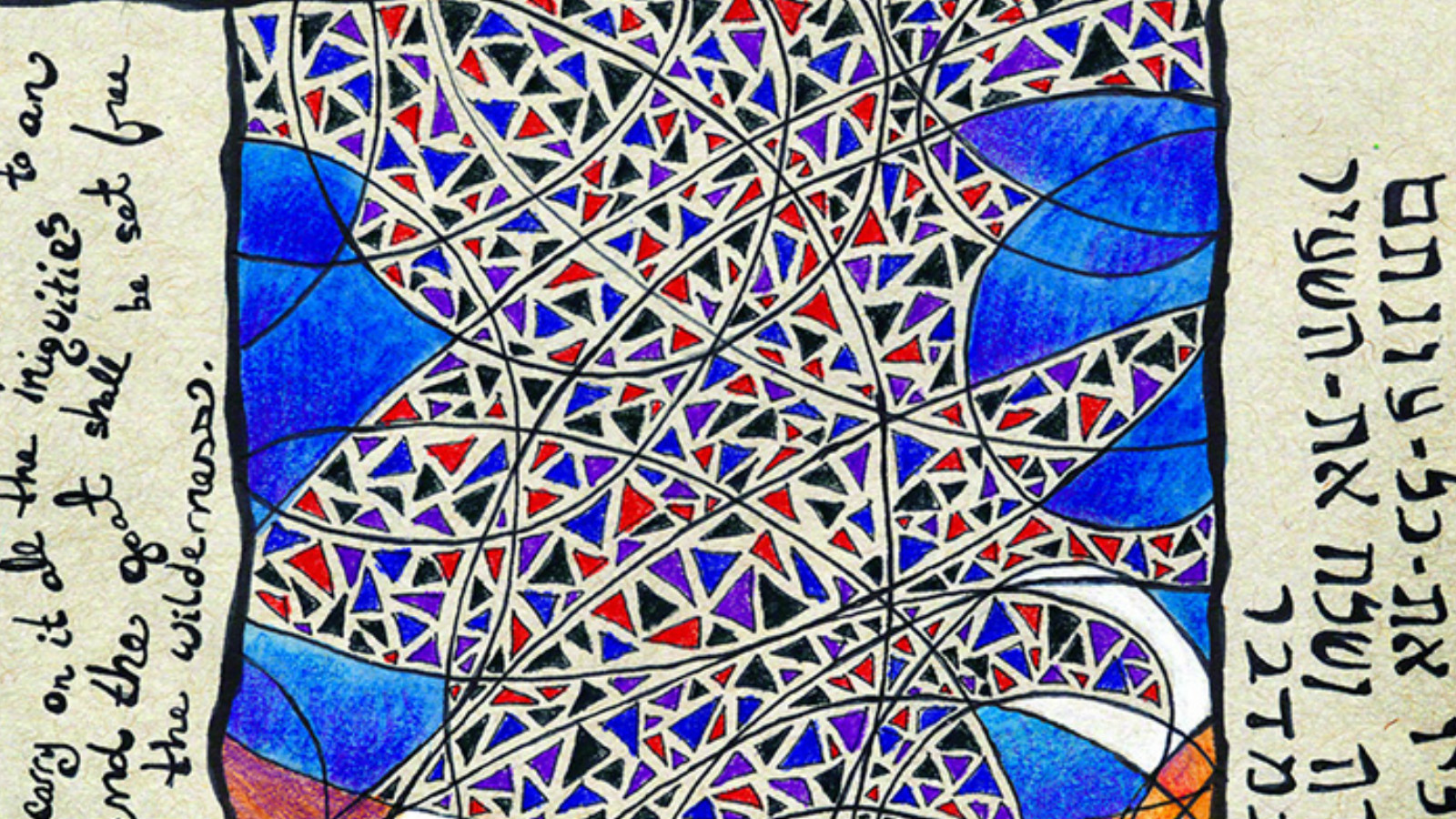

Commentary on Parashat Achrei Mot-Kedoshim, Leviticus 16:1 - 20:27

Parashat Kedoshim opens with the words kedoshim tihiyu – generally translated as “be holy.” Similar statements occur throughout this Torah portion. But what does “holy” mean? How is holiness created or achieved? How does our holiness relate to God’s holiness?

Toward the end of this portion, a similar verse states: “And you shall be holy to Me, because I, the Lord, am holy, and I separated you from the nations to be to Me.” This juxtaposition of holiness and separation might imply holiness is defined by separation. The verse, which comes in the context of the command to differentiate between animals that may or may not be eaten, seems to declare that Israel’s holiness stems from having been itself differentiated. God set Israel apart and called upon the people to set other things apart.

This approach seems to align with the opinion of several biblical commentators who understood holiness to be defined as abstaining from certain forbidden, or even just unbecoming, practices. If we stop here, we might take the command to be holy as an order to live an ascetic lifestyle. But as several midrashic texts note, the Torah was not given to angels but to people. Did God give the Torah to physical creations purely to tell us to negate our physicality?

Perhaps we can build on the idea of holiness as separate from with the idea of separation for. This can be seen in one of the Jewish terms for marriage: kiddushin – from the same Hebrew root as the name of this portion. The traditional formula recited under the marriage canopy is harei at mekudeshet li – “behold, you are sanctified to me.” Sanctification here is not simply about separation from other potential partners, but about designation for a unique relationship with the specified individual.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The 19th-century German Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch expresses this positive notion of holiness in his commentary when he writes that holiness means being prepared to use all our capabilities towards doing good. “It does not consist of neglecting, curtailing, killing, or doing away with any of one’s powers or natural tendencies,” Hirsch writes. “No single one of the powers and natural tendencies which are given to man is either good or bad in itself … They are all given to him for beneficial purposes to accomplish God’s will on earth.”

The 20th-century American Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik offers a similar perspective in his book Halakhic Man, suggesting that halakhah, or Jewish law, brings holiness from its divine roots into the world of the concrete. “An individual does not become holy through mystical adhesion to the absolute nor through mysterious union with the infinite … but, rather, through his whole biological life … Holiness is created by man, by flesh and blood. Through the power of our mouths, through verbal sanctification alone, we can create holy offerings.”

Rabbi Soloveitchik stresses the necessity of physical life in achieving holiness, which perhaps explains why such a wide spectrum of specific laws is interspersed throughout this portion with the general imperative toward holiness. His example of “holy offerings” refers to the human power to create holiness in an animal – not to set it aside for veneration, but to use it for a purpose in a Temple offering.

Holiness, then, is not just about separation from, but about designation for; it is not a passive state of having been set aside from the mundane, but an active state of being put to positive human use.

Many areas of Jewish law demonstrate that God may declare that something or someone can be holy, but that human action ultimately makes it so. For example: God sets certain days as holidays — or mikra’ei kodesh, literally “holy times” — but those dates only became holy once they were recognized by ancient rabbinic courts.

Holiness, as Rabbi Soloveitchik writes, begins with God, but that is only half the picture. We also make ourselves holy. One might say that God chooses what to make holy, but it only becomes so, its holy potential realized, through purposeful human use.

The phrase kedoshim tihiyu can be either descriptive or prescriptive, translated either as the imperative “be holy!” or the descriptive “you will be holy.” Perhaps it’s both. We the people are holy in potential because God is holy and because God granted us the power to designate ourselves and our lives – our real, physical lives – towards the highest, holy purposes.

Read this Torah portion, Leviticus 16:1 – 20:27 on Sefaria

Sign up for our “Guide to Torah Study” email series and we’ll guide you through everything you need to know, from explanations of the major texts to commentaries to learning methods and more.

Subscribe to A Daily Dose of Talmud: Daf Yomi for Everyone — every day, you’ll receive an email that offers an insight from each page of the current tractate of the Talmud. Join us!

About the Author: Sarah Rudolph is the director of TorahTutors.org and serves on the editorial teams of Deracheha: womenandmitzvot.org and Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought. She lives in Cleveland.