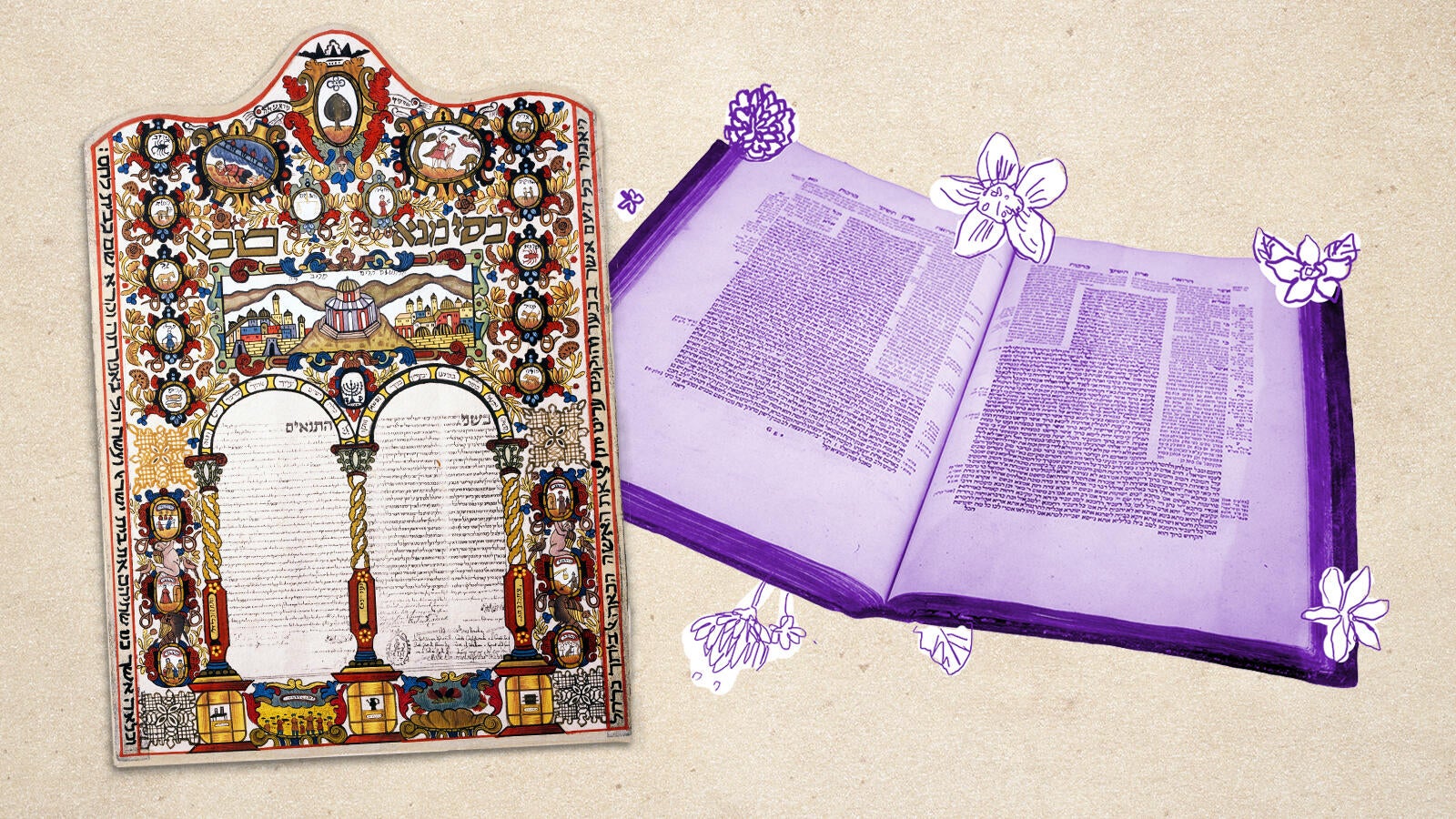

Tractate Ketubot, as the name implies, discusses the Jewish marital contract. These 112 pages of the Talmud don’t limit themselves specifically to this legally binding agreement, but explore the obligations of marriage more generally and frequently delve into other aspects of Jewish law, so much so that the tractate has earned the nickname Shas Katan, meaning “little Talmud.”

From the rabbinic perspective, a husband is legally required to sustain his wife, providing clothes for her as well as conjugal relations. His financial obligations to her continue even in the event of the dissolution of the marriage, through death or divorce. The primary purpose of the ketubah is to state the agreed amount of money that she is to receive should the marriage come to an end. In return, a woman is obligated to be sexually faithful to her husband and some of her means, either property or earnings, are assigned to him.

The rabbinic view was that marriage was sacred. A woman was consecrated to her husband just as the Jewish people are consecrated to their God. Love, when present, was a beautiful component of marriage, though that is little discussed in the Talmud, which is more invested in the legal side of one of the most complex contracts a person can enter into. Here is a quick overview of the contents of the 13 chapters of this tractate:

Chapter 1

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

This tractate opens with a discussion of which days are preferred for marriage because they allow the bride and groom time to prepare the feast and also allow for the possibility that the groom can sue the bride on the morning after the marriage should he suspect, upon sleeping with her, that she is not a virgin. This leads to a discussion of the definition of virginity and the means of determining if a woman is in fact a virgin. In certain cases when a man sues his bride for not being a virgin, she can produce proof in court that she is. A discussion of credibility with regard to lineage follows.

Chapter 2

This chapter concerns which testimony can be trusted in cases where the ideal testimony — two independent adult male and impartial witnesses — is not available. This chapter is also concerned with the ratification of documents that one party claims to be forgeries and the laws that govern a woman who has been captured by gentiles and is assumed to have been sexually abused by them (and therefore cannot marry a priest). Certain imperfect testimony can prove that she was not raped while in captivity — though not simply her own testimony. The Gemara also considers other cases in which imperfect testimony is permissible.

Chapter 3

This chapter deals with cases in which a man either seduces or rapes a woman who is forbidden to him. He may not marry her, but he does owe either her father or her money, which might differ depending on whether he forced himself on her and also on whether she is a virgin or not. He may also pay for her pain and humiliation, and whether that payment goes to her or her father is also discussed. This leads to a more general discussion of cases in which a person violates two laws at once and whether that can or should incur two punishments.

Chapter 4

This chapter deals with matters a father might decide for his minor daughter, including betrothing her to a husband and accepting a bill of divorce for her. He may also nullify her vows, pocket any money she earns, or that is given to her upon betrothal, or that she is given in settlement of a lawsuit. Once she is grown up, she controls more of these monies, though her father still retains some control until she marries. If the marriage is annulled, she is considered like an orphan even if her father is still alive. This chapter also considers the rights of a husband which are similar to those of a father except that a husband is entitled to usufruct, revenue generated from property the wife owns.

This chapter also concerns cases in which a husband accuses his wife of having been unfaithful to him while they were betrothed (and therefore not a virgin when they were married).

This chapter further details the obligations a man has toward his wife, including providing food, clothing and conjugal relations. He also must redeem her from captivity and pay for her medical and burial expenses. After death, his widow may continue to live in their shared home and derive sustenance from his estate. Her daughters are also supported until they reach adulthood, and her sons inherit her ketubah payment should she die.

The chapter ends with a discussion of a father’s obligation to feed his children, which only technically extends to age six. After that, it’s clear he was socially expected to continue their support even though it’s not legally required.

Chapter 5

In this chapter, we learn that while 100 and 200 dinars are the minimum ketubah payments (for a non-virgin and virgin, respectively), there is no maximum. A man is only obligated to pay the larger sum if the marriage progresses past betrothal to become a complete union (the precise moment this happens — be it under the huppah or under the sheets — is a subject of discussion). A man may not, however, go below the minimum.

In this chapter we also learn that a man cannot indefinitely delay a marriage as a strategy to avoid supported his betrothed — support begins after the agreed date for the marriage, whether or not a marriage has taken place.

The woman’s duties for the household include domestic labor, though a wealthy woman who was not raised to do these jobs is not required to cook and clean, as her husband must keep her in the style to which she has been accustomed. However, the rabbis believe it is not good for a woman (or anyone, for that matter) to be completely idle. A wife is also expected to do some amount of paid labor, the earnings of which are turned over to her husband. However, if she wishes to keep those earnings, she may strike a deal with him and forfeit her right to sustenance.

This chapter concludes with a man’s sexual obligations toward his wife. He owes her intercourse at regular intervals, though those intervals differ depending on his line of work.

Chapter 6

Not only are a woman’s earnings generally earmarked for her husband (unless she strikes a special deal with him, as described in the previous chapter), but so are items that she finds. Wealth that she inherits, however, belongs to her, though he may benefit from profit it accrues (for instance, if she inherits an orchard, he may claim the fruit).

Much of this chapter concerns the laws of dowries, which were not required but customarily given at the rate of 1/10th of the father’s estate (meaning the land that he owned, not movable property). Should a father die before his daughter was married, she could legally demand this amount from his inheritors. Large dowries could command a higher ketubah price.

Chapter 7

This chapter describes situations in which a court can require a couple to divorce. These include: (1) vows undertaken by either party, before or during the marriage, that interfere with the marriage or the parties’ fulfillment of marital obligations; (2) inappropriate conduct, such as immodest behavior or abrogation of certain social customs (in which case, the ketubah is immediately paid if the husband is guilty, and not paid if the wife is the guilty party); and (3) physical blemishes in either party, especially those discovered only after the marriage was contracted.

Chapter 8

This chapter delves more deeply into the husband’s right to usufruct — that is, benefiting from his wife’s property that remains her her possession. The ins and outs of this discussion include boundary cases such as a betrothed woman who inherits property or a levirate widow who inherits property while waiting for her yavam to marry her. There is also a concern about property that the wife owns which does not yield produce, which, in some cases, may be sold to purchase property that does. At the time of divorce, already harvested produce belongs to the husband, while produce still growing on the plants belongs to the wife. And so forth.

Chapter 9

Concluding the discussion of usufruct, a husband can waive his rights to usufruct, but not to inheriting his wife’s property upon her death.

This chapter also explores some of the laws of oaths within a marriage. In rabbinic understanding, an oath is a kind of judiciary proof — when a person swears to something in court, this is considered reliable (though less reliable than the testimony of witnesses). Here, the rabbis discuss cases in which a wife might be required to swear an oath that she has not already received her ketubah payment, in full or part, before collecting what is owed to her.

This chapter also describes how a woman might collect money from her husband’s estate should he die, especially in cases where there is not enough money to cover her ketubah or, in the case of multiple wives, their ketubot.

This chapter also discusses how a woman might collect payment if her ketubah is misplaced or if she has more than one (supposing the husband wrote a supplemental document for her).

Chapter 10

This chapter opens with a discussion of cases in which a husband dies, leaving multiple widows and an estate that cannot pay all their ketubot. How are the limited funds apportioned? In general, wives married earlier take precedence and wives who are still living take precedence over the heirs of deceased ones. One particularly interesting case is that in which the wives all take equal precedence but have ketubah contracts of differing sums. Other laws of inheritance are discussed as well.

Chapter 11

This chapter describes how a widow may sustain herself by selling off her husband’s deceased property in pieces at six-month intervals, and how the courts can help ensure that a woman sells the property for what it is actually worth (thereby shortchanging neither herself nor her husband’s heirs).

This chapter also considers cases in which a problem in the marriage is discovered after the marriage has taken place — perhaps that the woman is an aylonit who does not develop secondary sexual characteristics and is infertile, or perhaps it is discovered that the husband and wife are related to one another and their relationship makes their marriage forbidden according to rabbinic law. Such marriages are dissolved and the women are not entitled to their ketubot. Likewise, a girl who is promised in her youth to a husband by a mother or brother (assuming her father is dead) and, upon coming of age, rejects the marriage — she too does not receive her ketubah.

Chapter 12

A husband who promises in the marriage contract to feed his wife’s daughter from a previous relationship continues to do so even if the marriage ends, and even if the daughter finds another means of sustenance (such as her own husband) because such a contractual obligation is not contingent on the marriage itself.

This chapter also discusses the widow’s right to consider residing in her home after her husband dies. If she prefers to return to her father’s household, the heirs pay her what it would have cost to keep her housed within their family.

A woman has up to 25 years to claim her ketubah. After that, she is considered to have forfeited it.

This chapter also contains a famous series of stories about the death of Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi, who was suffering terribly at the end while his students prayed to keep him alive. His maidservant dropped a jug from the roof of his home, interrupting his prayers and allowing his soul to depart. This story often figures into Jewish ethical discussions about euthenasia.

Chapter 13

This chapter details the laws concerning a woman whose husband is overseas for a long time. She can, with the help of the court, sustain herself from his estate. But if a third party steps up to sustain her, he cannot sue the husband to recover his costs.

A husband cannot compel his wife to move a great distance from home, but he can compel her to move to the land of Israel. Likewise, she can compel him to move to Israel, and neither party can compel the other to move away. What is compelling? If a husband or wife refuses to move to the land of Israel, the other can dissolve the marriage and claim the ketubah money (i.e. he keeps it from her, or she gets it, depending on which party wanted to move to the holy land).

Speaking of moving, a husband may choose to pay a ketubah contract either from the currency of the place where the couple got married or the place where the couple currently lives.

This chapter circles back to questions of oath-taking and inheritance before moving on to the strict prohibition against judges accepting bribes. This includes a series of stories that illustrate the dangers of taking a bribe, however small. The tractate concludes with praises of the land of Israel.