As a graduate student, I studied the origins of the Passover seder. This entailed reading all the textual material on the subject and trying to imagine the ritual as it looked back when the Jerusalem Temple stood. Here’s my take:

A few days before Passover, Jewish families would trek en masse to Jerusalem where, on the 14th of Nisan, they would ascend to the Temple, a thrumming 36-acre complex that smelled constantly of smoke, blood, burning flesh and lye. They would be joined there by Jews from around the world and thousands of small animals being led (quite literally) to the slaughter. Once the animal’s lifeblood had been dashed on the altar, the carcasses were borne on shoulders back to wherever the families were staying, oftentimes in outdoor encampments. As darkness descended, the animal was roasted over an open flame and eaten with bitter herbs and fresh flatbread. All around, other Jews were doing the same, their campfires dotting the hills and wrapping the city in the acrid smell of barbeque. Since the Torah obliges each family to eat the entire animal before dawn, everyone probably stuffed themselves with meat — a rare and expensive treat in those days — before falling into a food coma sometime in the middle of the night.

Sometimes when I’m at a Passover seder, sitting for hours on a folding chair made only marginally more comfortable by the pillow awkwardly placed against my back, I find myself imagining not, as the Haggadah implores us, what it felt like to go forth from Egypt, but what it might have felt like to experience the Jerusalem Passover celebration that my ancestors did 2,000 years ago. In 2013, I came one step closer to finding out. But before I describe that, I need to take us even further back in history.

Some 2,500 years ago, the ancient Israelites split into two ethnic communities: Judeans and Samaritans. Both groups continued to worship the God of Israel and considered the Five Books of Moses their sacred scriptures. Both groups also had Temples — the Judeans in Jerusalem and the Samaritans further north on Mount Gerizim. But then the Judean Temple was destroyed and the rabbis came along and transformed the religion with their legal interpretations of sacred texts.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

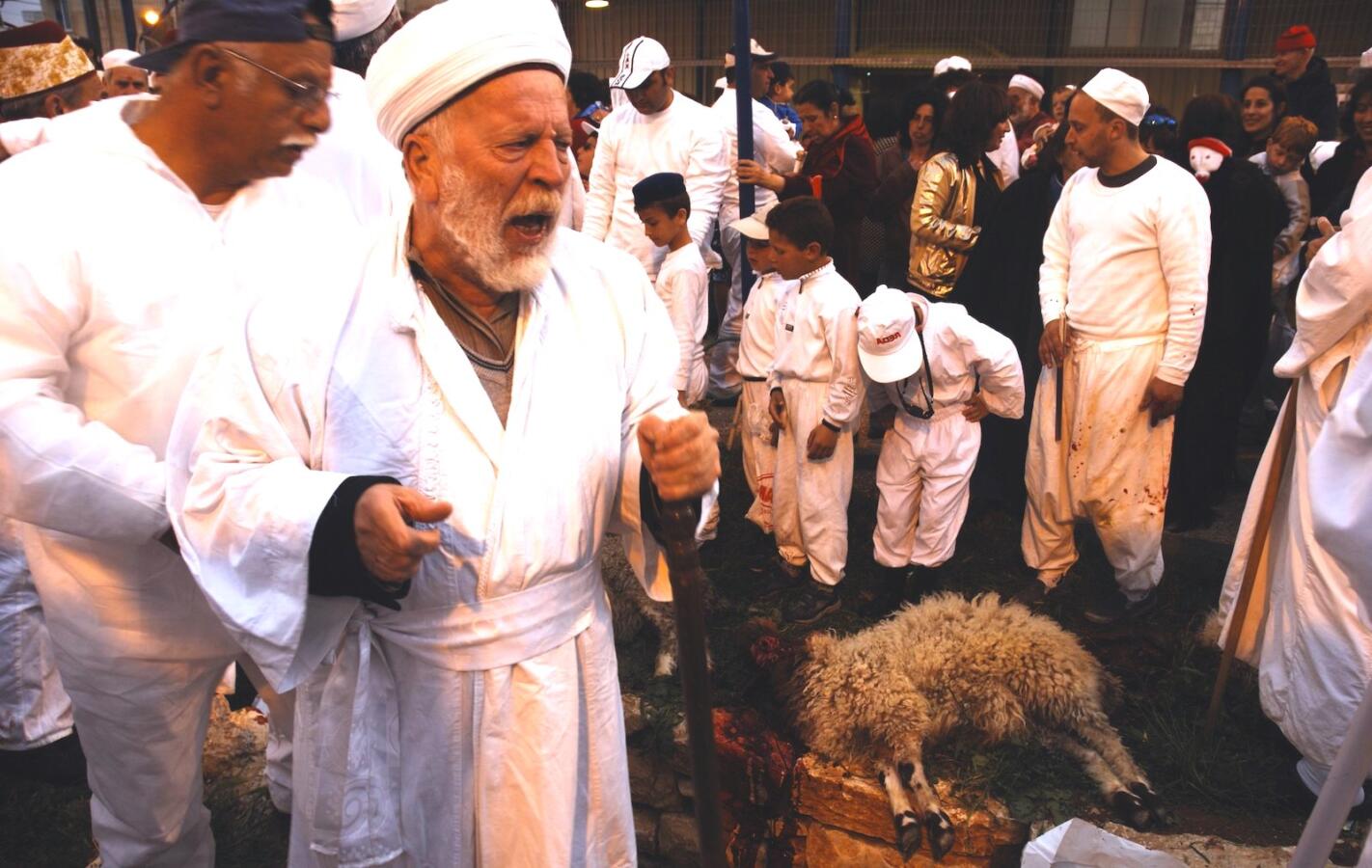

The Judeans became the bearers of the Judaism we know today. But the Samaritans are still around too, and they still practice Passover more or less as the Bible prescribes. Every Passover they take sheep to the spot where their Temple once stood and slaughter them at sundown. Then they skin them, spit them and roast them in huge fire pits before tucking into the feast. Sound familiar?

Tourists are invited to come watch the first part of the ritual. And because Jews and Samaritans have calculated the calendar differently for millennia, in 2013 the festival fell out on a night that was not actually Passover for me. So I went.

When I first arrived, the Samaritans were streaming to the center of town with their obviously anxious sheep, who were tied to poles atop irrigated channels to wash away the mess. It probably bears mentioning here that I’m a vegetarian, and the spectacle made me very uncomfortable, but I don’t think I was the only one. The tension in the air was inescapable.

After half an hour of chanting, precisely at sundown, the blades came down. I didn’t watch, but I remember feeling relief when it was over. Now began the work of preparing the animals for roasting, which was graphic but somehow less painful than anticipating the slaughter. The mood shifted entirely and there was relief and excitement in the air. The Samaritan ritual felt nothing like my Passover, but it was impossible to be there and not ride the emotional rollercoaster — to experience the dread of slaughter and the cathartic relief when it was over.

I imagine this is what my ancestors must have experienced on Passover, but on a much larger scale. If I experienced a kind of catharsis by merely observing hundreds of people with no Temple perform this ritual, what must it have felt like in ancient times to join thousands of pilgrims for a multi-day festival in a magnificent marble Temple complex probably unlike few other structures they had ever seen? I can only imagine.

There are few opportunities for this sort of catharsis in modern life — and that is a feature, not a bug. Our meat comes in shrink wrap, at a far remove from the killing it entails. Our medical care and (typically) our deaths take place in sanitized institutions, often under pain-killing anesthetics. Our ritual lives are little different, drained of the slaughter and sacrifice that mostly defined them in ancient times.

Scholars have historically argued that the rabbis invented the Passover seder to replace the paschal sacrifice, which could no longer be offered once the Temple was destroyed. My research showed this was not the case — the rabbis were eager to bring back the sacrifice and did not imagine any ritual as more than a temporary substitute until the Temple was rebuilt. For them, Passover was the paschal sacrifice. And because they frequently speak of the Temple with words of longing, it’s clear that anything else they did lacked the emotional experience of performing the Temple service.

Is there a way to experience this kind of catharsis — the kind that exhausts and energizes and makes one feel that something truly exceptional is happening — as part of modern Jewish ritual? I’m not sure. I’m not interested in bringing more violence into our lives, but I am aware that an emotional dimension to Judaism has been lost. I wonder what Judaism would look like if we could find a way to recapture it.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on Mar. 25, 2023. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.