The Book of Genesis ends with the story of Jacob going down to Egypt with his family. The first chapter of Exodus tells how the 70 members of Jacob’s s clan evolved into a large people, cruelly enslaved by the kings of Egypt. The enslavement is presented in the Bible as a crucible that forged the nation of Israel. Oppressed for several centuries, the Hebrews suffered until Moses, of the tribe of Levi, brought up in Pharaoh’s household, led them to freedom in the name of God, an omnipotent deity unknown to the Hebrews prior to their liberation.

The Exodus Narrative

The story of the Exodus is related in a few dramatic chapters: 600,000 men left Egypt on a long trek to freedom. God punished their enemies (the ten plagues of Egypt), drowned Pharaoh’s army with its chariots and cavalry in the Red Sea, and brought them to Mount Sinai where they witnessed the revelation and received the Decalogue–God’s commandments to his people.

The First Commandment is the essence of Jewish monotheism: “I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before me” (Exodus, 20:2‑3). By the time they reached the frontiers of Canaan after forty years in the desert, the Israelites had become a strong, united nation, and were ready to conquer the Promised Land.

Is Exodus History?

The historical validity of this narrative is controversial. Some scholars stress the lack of Egyptian evidence testifying to the enslavement of the Israelites, pointing out that very little Egyptian influence is discernible in biblical literature and in ancient Hebrew culture. Other scholars, however, claim that it is highly improbable that a nation would choose to invent for itself a history of slavery as an explanation of its origins. If such a tradition exists, it must reflect an historical truth.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Were the Israelites Slaves?

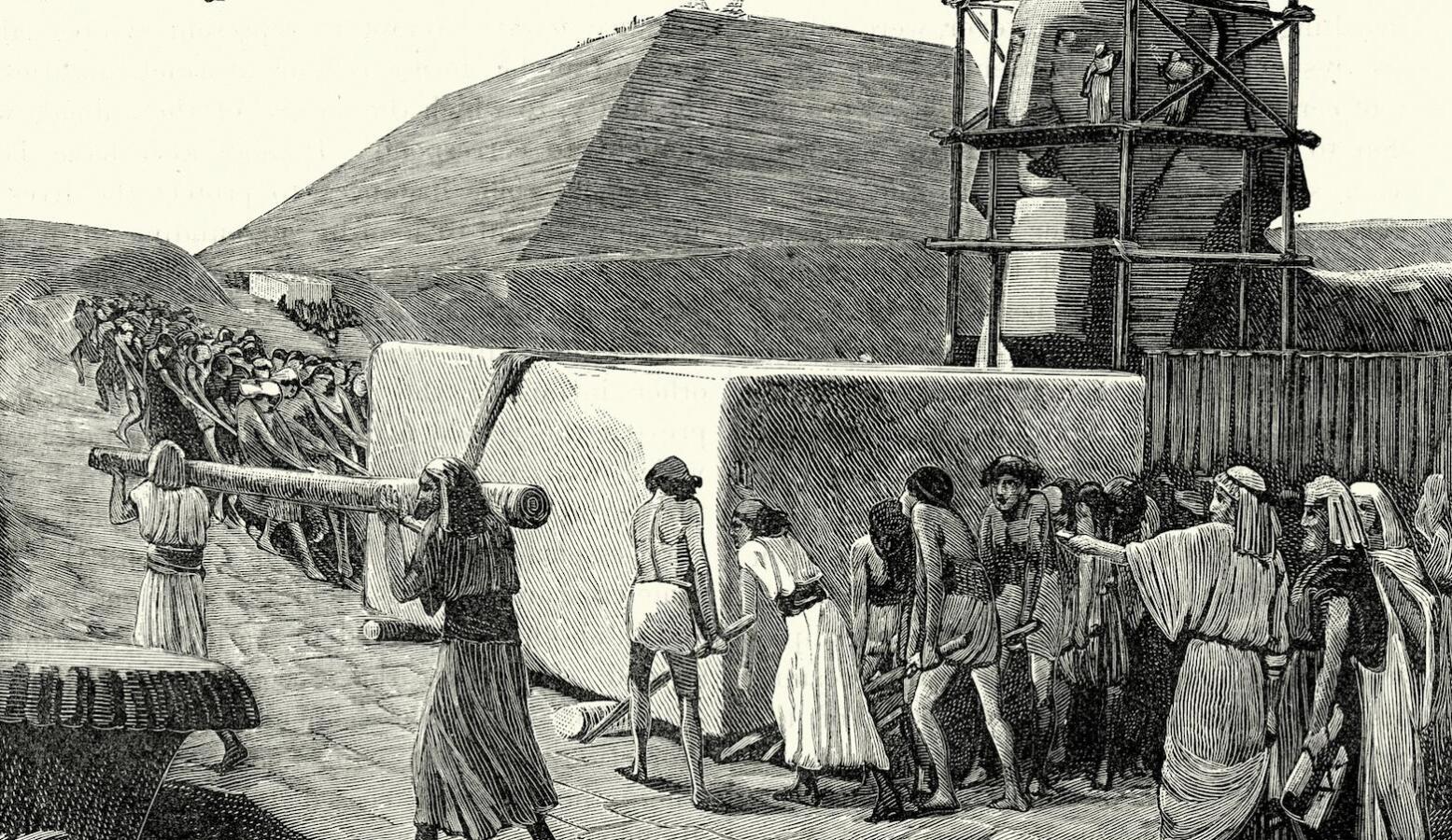

There is no doubt that slavery played a major role in the structure of the Egyptian state. It is also true that some form of single‑god worship was introduced into Egypt by Akenaton in the middle of the fourteenth century B.C.E., and this may have been a source for Jewish monotheism. Finally, the reign of Ramses II (1290-1212 B.C.E.), known for its costly wars and vast building enterprises, may well have been the era of cruel oppression described in Exodus.

But the only contemporary Egyptian source which actually mentions Israel is the stela (pillar with inscription) of King Merneptah from the fifth year of his reign (1207 B.C.E.), recording among his many victories: “Carved off is Ashkelon, seized upon in Gezer…Israel is laid waste, his seed no more.” This inscription implies that an entity named Israel existed in Canaan at the time, yet it is difficult to determine precisely what it was. One thing, however, may be regarded as certain: if the Israelites indeed emerged out of Egypt, their migration took place before the end of the 13th century B.C.E.

Explaining the Passover Miracles

This single fact, however, does not resolve the enigma. Obviously, the orthodox tradition accepts the biblical account literally, despite all the miracles it describes. There are scholars who seek to explain the miraculous events in rational and natural terms. They refer to ancient disasters which befell Egypt–floods, drought, slave rebellions, and invasions. Could these not be the ten plagues of Egypt? And the drowning of Pharaoh’s army in the Red Sea–can it not be explained by the ebb and flow of the marshes between the Nile and the Sinai Desert?

Problems and Contradictions in Exodus

Other scholars, however, totally reject the historical validity of Exodus. The story of Ipu‑wer, they say, describes the anarchy in Egypt at the end of the third millennium B.C.E. and has no bearing on the biblical story; and 600,000 men (“not counting dependents”) means that approximately two million Hebrews left Egypt– is it possible that such a vast emigration left no trace in Egyptian sources? The biblical narrative, they point out, is full contradictions concerning the topography and the sequence of events–a feature typical of folktales, not of historical texts.

Intermediate Theories about Exodus

Between the two opposing views there are several intermediary theories. One hypothesis is that the Israelites left Egypt in two waves, and that by the time the second wave departed–in the middle of the thirteenth century–the first group had already settled in the land of Canaan, mostly around the town of Shechem in Samaria. Another possibility is that there was no organized mass emigration, but rather a constant flow of thousands of people from different Semitic tribes who left Egypt, roamed the desert, slowly infiltrating the land of Canaan where they eventually formed a single nation.

Reprinted with permission from A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People edited by Eli Barnavi and published by Schocken Books.

<!–

Yair Hoffman is a Professor of Bible at Tel Aviv University.

This article is reprinted with permission from A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People edited by Eli Barnavi and published by Schocken Books. © 1992 by Hachette Litterature.

–>