The Bible depicts Saul as a study in contrasts. Although he was Israel’s first king, he was ultimately rejected (1 Samuel 15:10-11). His dark, fitful personality suffers by contrast with the two legendary figures between whom he seems wedged–Samuel the prophet-priest and David, Saul’s hero-successor.

Facing the Philistines

The Bible describes Saul rising to the throne in the face of the Philistine military threat. The Philistines are known both from the Bible and from the extra-biblical sources. Egyptian inscriptions mention them as one of the so-called Sea Peoples. Apparently, they originally came from the Aegean area or from southern Anatolia.

The Sea Peoples settled in various parts of the Egyptian province of Canaan, probably with Egypt’s agreement. The Philistines occupied the coastal plain between Gaza and Jaffa.

Eventually, the Philistine military expansion near Aphek brought the Philistines close to the territory occupied by the Israelite confederation. The Philistines were apparently skilled warriors who used the most advanced military equipment of their time. Their weapons were made of both bronze, the predominant metal until about 1200 B.C.E., and iron, which was becoming increasingly available.

The Choice of Saul

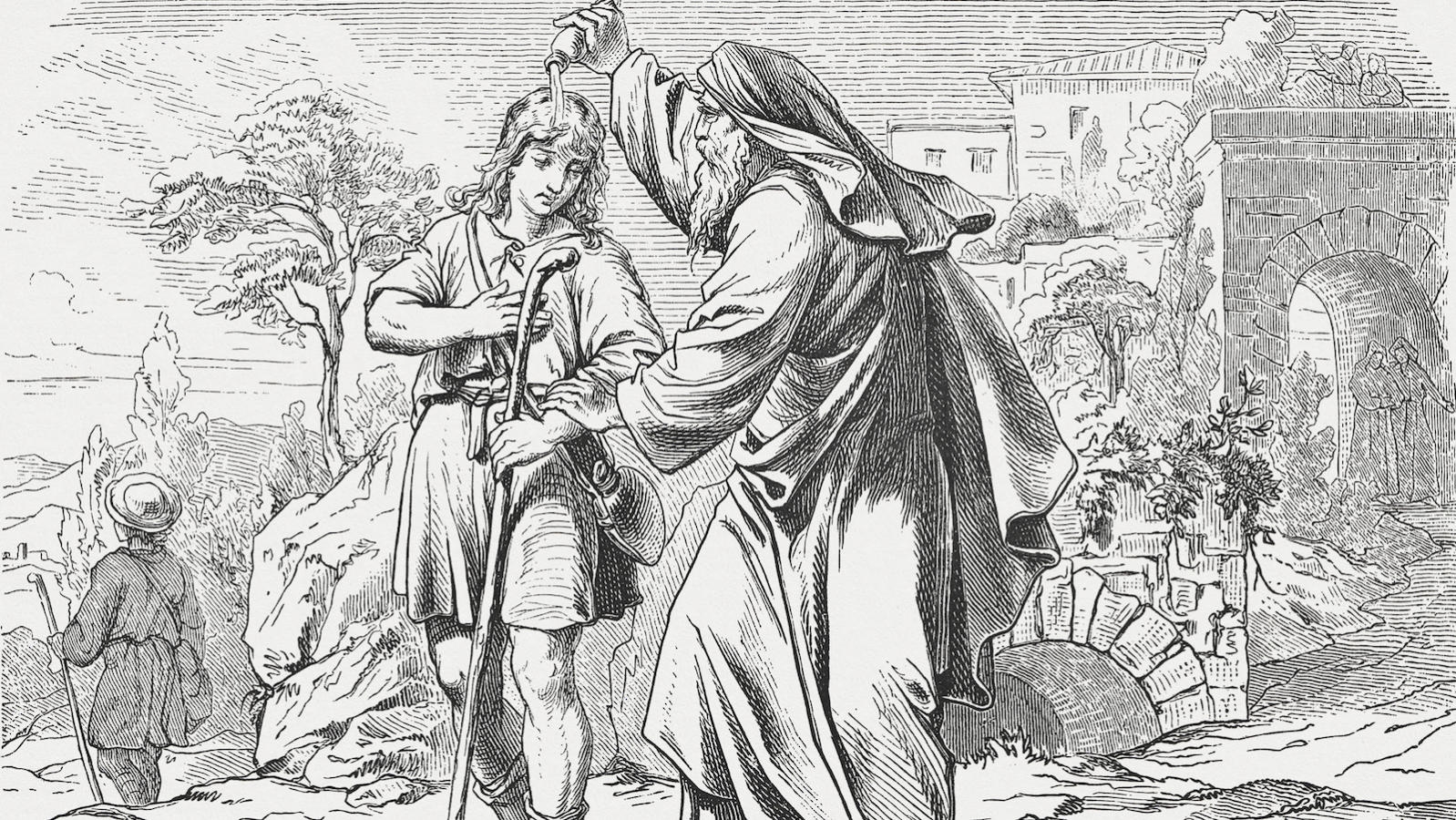

Facing these dire circumstances, the Israelite tribes determined that they must have a king. The story of the choice of Saul as king appears in three different traditions: In the first, Saul is looking for his father’s lost she-asses when he meets Samuel, who anoints him prince (nasi) over Israel (1 Samuel 9:3-10:16). In the second tradition, Saul is hidden among baggage at Mizpah when Samuel casts lots to choose the king (1 Samuel 10:17-27).

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In the third and probably most reliable tradition, Saul, at the head of the Israelite columns, has rescued Jabesh-Gilead from an Ammonite attack, and the people, with Samuel’s agreement, proclaim their allegiance to Saul at Gilgal (1 Samuel 11-15). In each of these accounts, Saul is installed and anointed as king by Samuel, now an old man.

Samuel was regarded as the last of the judges (1 Samuel 7:6,15,8:1-3), the charismatic leaders who emerged at time of crisis. Another tradition, probably a later one, regarded Samuel as a prophet (1 Samuel 3:20). He also officiated at the tabernacle at Shiloh, where the Ark was kept, which means he was a priest.

But Samuel’s leadership was regarded as insufficient. The tribal elders apparently felt that the appointment of a king was a historical necessity: “Now appoint for us a king to govern us like all the nations,” they told Samuel (1 Samuel 8:5) Saul, a Benjaminite, seems to have been chosen because he was tall and strong and well qualified to wage war against Israel’s enemies.

Like earlier charismatic leaders, Saul’s principle task was to conduct a war of liberation. Saul’s successful expedition against the Ammonites at Jabesh-Gilead (1 Samuel 11: 1-11) was no doubt an important consideration in his selection. Now he was called upon to lead his people against the Philistines, people who were well organized, well equipped and motivated by an expansionist ideology that included plans to bring the whole country west of the Jordan under its control.

Saul the Warrior

“There was hard fighting against the Philistines all the days of Saul, and when Saul saw a strong man, or any valued man, he attached him to himself” (I Samuel 14:52).

The Philistine war thus became a guerrilla war, characterized by ambushes and surprise attacks against enemy posts. Generally, it did not involve great numbers of fighters. Saul had only about six hundred men with him near Gibeah (1 Samuel 14:2). Unfortunately the Bible gives only brief intimations of the details of the continuing war with the Philistines. Saul probably succeeded in driving the Philistines out of the central part of Israel. But the Philistines did not give up. They apparently attacked form the south, threatening Judah in a confrontation in which a young Judahite named David distinguished himself (I Samuel 17) [?]

Other than the Philistine war, which seems to have been the principle feature of Saul’s reign, the biblical text mentions wars against the Moabites, the Ammonites, the Edomites, the king of Zobah and the Amalekites (1 Samuel 14:47-8) [?]

Saul’s Reign: An Historical Assessment

We do not know how long Saul ruled. According to the traditional Hebrew text (the Masoretic text) which unfortunately is badly preserved at this point, Saul became king when he was one year old! And his reign lasted only two years. (1 Samuel 13:1). This of course seems improbable, and several commentators correct the text to read “twenty-two years,” but this remains conjectural.

It is difficult to give a balanced historical assessment of Saul’s reign. In the biblical tradition, he seems to be presented as the typical bad king in contrast to his adversary and successor David. This contrast is the central theme of stories in 1 Samuel 16-27, the bulk of which seems to have been written by David’s companion and priest Abiathar (cf. 1 Samuel 22:20) or someone close to him. These chapters may contain some reliable information, but it is represented in a one-sided and tendentious way. They describe, in somewhat divergent traditions, the stormy relationship between Saul and young David.

David and Saul

David had distinguished himself in the Philistine wars and had been given Saul’s second daughter, Michal, in marriage. Saul became increasingly jealous of David, accusing his son-in-law of conspiring against him. On several occasions, Saul tried to kill David. David fled to Judah but Saul pursued him. Finally, David took refuge in Philistine territory.

Written from David’s viewpoint, the stories in I Samuel 16-27 tend to depict David as right in rebelling against Saul and seeking refuge in Philistine territory. But they also reveal that people from Bethlehem in Judah joined Saul in battle when the Philistines tried to invade the central hill country from the southwest (1 Samuel 17:1). Saul obviously exerted some political influence south of Jerusalem in the northern mountains of Judah, preparing he way for the federation of Israel and Judah under David.

The historicity of many of Saul’s other wars, however, is doubtful. The wars against the Moabites, the Edomites, the king of Zobah and even the Amalekites (1 Samuel 14:47-48, 15) may simply be a transposition from David to Saul made by the Judahite historian because he had so little information about Saul. Such wars far from Saul’s home seem improbable, especially when the Philistine threat was so strong and Saul’s army was so poorly organized.

Saul’s Reign

Unfortunately, we are left with little solid information about Saul or his reign. All that can be said with confidence is that Saul seems to have been named king so that he would lead the Israelites in their wars against the Philistines.

Saul’s kingdom was not very large. It probably included Mt. Ephraim, Benjamin and Gilead. He also exerted some influence in the northern mountains in Judah and beyond the Jezreel Valley. Instead of having a capital city or a palace, Saul set up his tent “in the outskirts of Gibeah under the pomegranate tree which is at Migron” (1 Samuel 14:2) or in Gibeah where he sat “under the tamarisk tree on the height with his spear in his hand and all his servants (i.e. ministers) were standing about him (1 Samuel 22:6).

The Archeological Record

Saul’s “kingship,” as might be expected from the biblical record, left hardly a trace archeologically speaking. Surveys and excavations in the hill country of Manasseh, Ephraim and Benjamin and at sites like ‘Izbet Satah have revealed farms, small villages, and open-air cult places on hilltops. To the south, in northern Judah, settlement was even sparser.

The fortified site of Khubert ed-Dawwara, northeast of Jerusalem, had perhaps one hundred inhabitants, and this was large for Saul’s kingdom. The principle Israelite site of the previous period, Shiloh, seems to have been destroyed in the mid-11th century B.C.E. by an intense conflagration. This destruction is often attributed to the Philistines as a follow-up operation after their victory at Ebenezer (1 Samuel 4). Shiloh is mentioned only once in the stories of Saul and David (1 Samuel 14:3).

Archeology seems to confirm that until about 1000 B.C.E., the end of Iron Age I, Israelite society was essentially a society of farmers and stockbreeders without any truly centralized organization and administration. Recent population estimates set a figure of about 50,000 settled Israelites west of the Jordan at the end of the eleventh century B.C.E.

By contrast, Philistine urban civilization was flourishing in the 11th century B.C.E. as revealed by recent excavations at Ashdod, Tel Gerisa, Tel Miqne (biblical Ekron) and Askkelon.

Saul’s reign ended in total failure with his tragic death. After the rout on Mt. Gilboa, the Israelite revolt against Philistine domination seemed hopeless. Under the leadership of Saul’s adversary, David, however, the fight for independence from the Philistines–the raison d’etre of Saul’s kingship–was taken up once again.

Reprinted with permission from Ancient Israel: From Abraham to the Roman Destruction of the Temple, edited by Hershel Shanks (Biblical Archaeology Society).