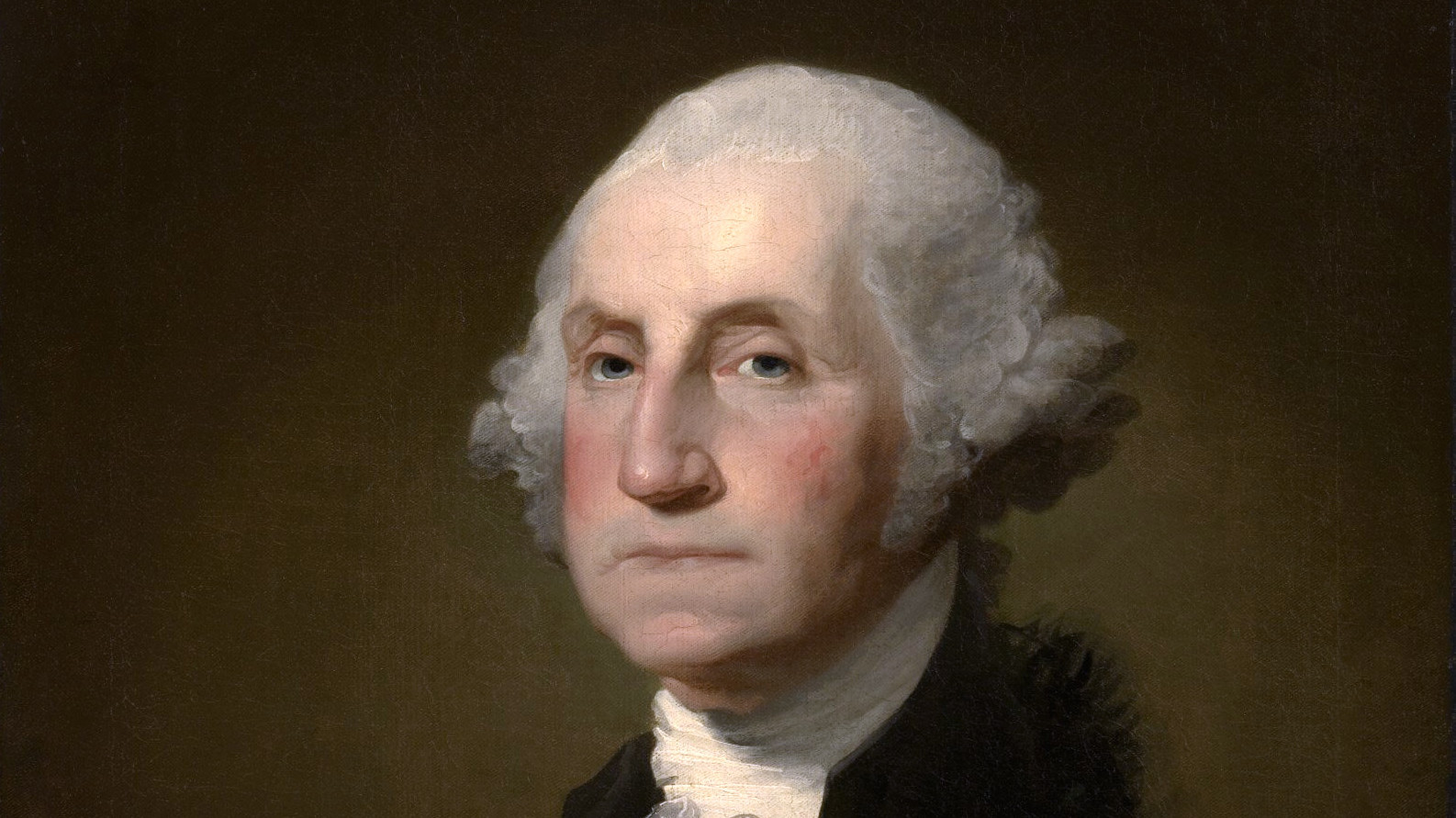

On August 17, 1790, Moses Seixas, the warden of Congregation Kahal Kadosh Yeshuat Israel, better known as the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, penned an epistle to George Washington, welcoming the newly elected first president of the United States upon his visit to the city. Newport had suffered greatly during the Revolutionary War. Invaded and occupied by the British and blockaded by the American navy, hundreds of residents fled, and many of those who remained were Tories. After the British defeat, the Tories fled in turn. Newport’s nineteenth-century economy never recovered from these interruptions and dislocations.

Washington’s visit to Newport was largely ceremonial–part of a goodwill tour Washington was making on behalf of the new national government created by the adoption of the Constitution in 1787. Newport had historically been a good home to its Jewish residents, who numbered fewer than 500 at the time of Washington’s visit. The Newport Christian community’s acceptance of Jewish worship was exemplary, although at this time individual Jews did not possess full voting and office holding rights as citizens of Rhode Island. The Jews of Newport looked to the new national government, and particularly to the enlightened president of the United States, to remove the last of the barriers to religious liberty and civil equality confronting American Jewry.

Moses Seixas’s letter on behalf of the Newport congregation–he described them as “the children of the Stock of Abraham”–expressed the Jewish community’s esteem for President Washington. The congregation expressed its pleasure that the God of Israel, who had protected King David, had also protected General Washington and that the same spirit which resided in the bosom of Daniel and allowed him to govern over the “Babylonish Empire” now rested upon Washington. While the rest of world Jewry lived under the rule of monarchs, potentates, and despots, as American citizens the members of the congregation were part of a great experiment: a government “erected by the Majesty of the People” to which Newport Jewry could look to ensure their “invaluable rights as free citizens.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Seixas expressed his vision of an American government in terms that have become a part of the national lexicon. He beheld in the United States:

A Government which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of citizenship: – deeming every one, of whatever nation, tongue or language equal parts of the great Governmental Machine:–This so ample and extensive federal union whose basis is Philanthropy, mutual confidence, and public virtue, we cannot but acknowledge to be the work of the Great God, who ruleth the Armies of Heaven, and among the Inhabitants of the Earth, doing whatsoever seemeth [to Him] good.

Seixas closed his letter to Washington by asking God to send the “Angel who conducted our forefathers through the wilderness into the Promised Land [to] conduct you through all the difficulties and dangers of this mortal life.” He told Washington of his hope that “when like Joshua full of days, and full of honour, you are gathered to your Fathers, may you be admitted into the Heavenly Paradise to partake of the water of life, and the tree of immortality.”

Not surprisingly, it is Washington’s response, rather than Seixas’s epistle, which is best remembered and most frequently reprinted. Washington began by thanking the congregation for its good wishes and rejoicing that the days of hardship caused by the war were replaced by days of prosperity. Washington then borrowed ideas–and some of the words–directly from Seixas’s letter:

The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for giving to Mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights.

For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection, should demean themselves as good citizens.

Washington’s concluding paragraph perfectly expresses the ideal relationship among the government, its individual citizens and religious groups:

May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while everyone shall sit under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.

The president closed with an invocation: “May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.”

The letter, a foundation stone of American religious liberty and separation of church and state, is signed, simply, “G. Washington.” Each year, Newport’s Congregation Kahal Kadosh Yeshuat Israel, now known as the Touro Synagogue, re-reads Washington’s letter in a public ceremony. The words deserve repetition.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.