Immigrant Jews continued [around the turn of the 20th century] to pour into the Lower East Side and, to a lesser degree, into Chicago’s West End and Jewish ghettos in Philadelphia and Boston; few of the smaller cities and towns of the American interior offered so great a possibility of Jewish communalism and Yiddish-based culture as the great cities. Equally important, the ghettos, particularly the largest one in New York’s Lower East Side, offered the possibility of employment for Jews. At the time that masses of Eastern European Jews were coming to America, the garment industry was undergoing rapid expansion, and New York City was central to this development. Many immigrant Jews worked in New York garment factories.

By 1910 the city was producing 70 percent of the nation’s women’s clothing and 40 percent of its men’s clothing, creating jobs for newly arriving Jews. Even if we discount their exaggerations (only 10 percent of Eastern European immigrant labor force were actually trained tailors), these Jews brought with them from the old countries significant skills in garment work, one of the few occupations open to Jews in 19th-century Europe.

Jobs for Jews

As early as 1890 almost 80 percent of New York’s garment industry was located below 14th Street, and more than 90 percent of these factories were owned by German Jews. Lower New York, therefore, was a powerful magnet for the Eastern Europeans throughout the period of mass immigration. Immigrants were attracted by jobs and by Jewish employers who could provide a familiar milieu as well as the opportunity to observe the Sabbath. By 1897 approximately 60 percent of the New York Jewish labor force was employed in the apparel field, and 75 percent of the workers in the industry were Jewish.

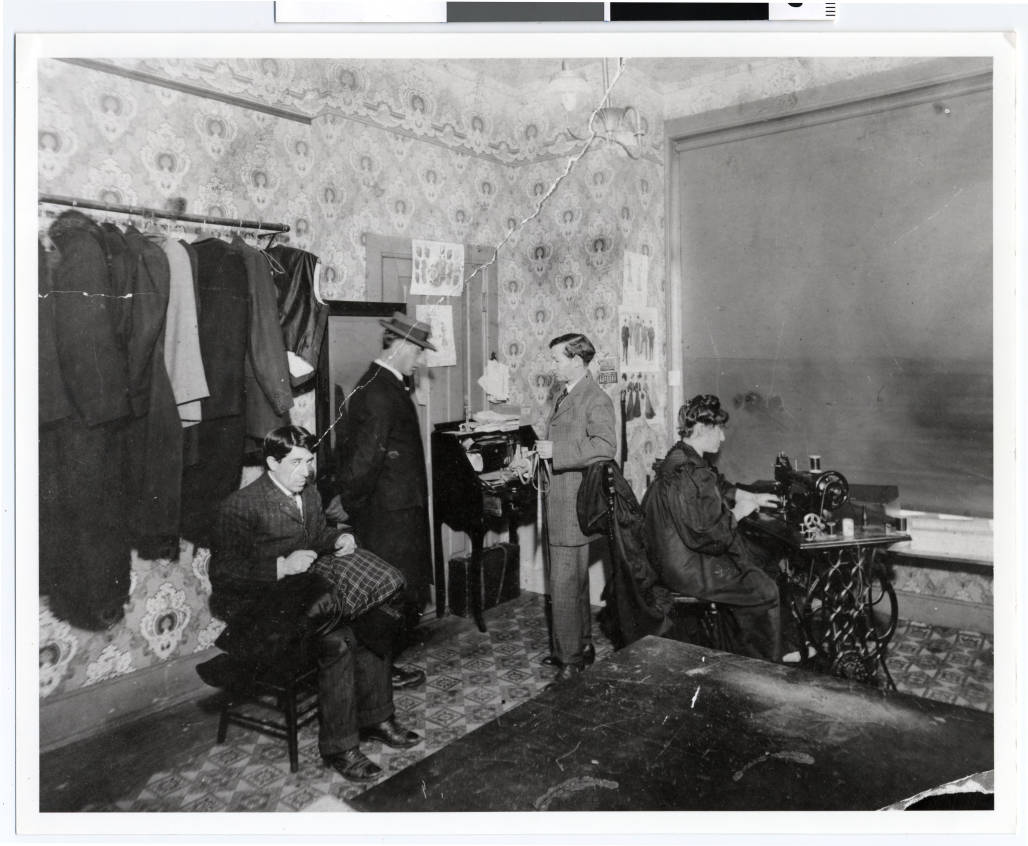

Within the American needle industry there were three systems and three sites of production. The oldest was the family system, which had been dominant under Irish and German influence in the mid-19th century. Work was divided among family members and was done at home. In the 1870s, homework, or outside manufacture, declined, as factories–the second mode of production–became dominant. But with the coming of Eastern European Jews, there sprang up a third form of production–the contracting, or sweatshop, system, a variant of the family system.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Contracting utilized section work, which was designed to exploit the economies of a minute division of labor. The contractor, usually an immigrant who had been in America somewhat longer than the newest arrivals (greenhorns) picked up precut, unsown garments from the manufacturer. He then supervised in his own home, or in a loft or tenement room converted to a shop, a collection of operators: basters, pressers, finishers, zipper installers, buttonhole makers, and pocket makers. Some section and finishing work was given to a subcontractor, who found people willing to take that work into their own apartments.

Exploitative Conditions

Exploitation–including exploitation of the self (as the contractors and subcontractors and their family members often worked alongside the employees)–was more intense than in factories and inside shops. The contractor’s profit margin was low and so, therefore, was pay. The sweatshop, in addition, demanded extremely long hours in terribly close quarters.

Abe Cahan [an immigrant author], in his short story “Sweat-Shop Romance,” described the kitchen in a small Essex Street apartment, filled to overflowing with bundles of cloth, shears, cotton spools, finished garments, people, pots, and pans. Also present was a “red-hot kitchen stove,” which made the work space a sweatshop in the literal sense.

The worst conditions of the factory and the tenement had come together in one place. Yet to the newly arrived immigrants there were advantages to the sweatshop system. Workers could communicate in their own language. The work, however arduous, did not prevent the performance of religious duties, the observance of the Sabbath, or the celebration of religious festivals. Moreover, working together in small units, immigrants thought they could preserve the integrity of their families. The “homes of the Hebrew quarters are its workshop also,” reported journalist Jacob Riis:

“You are made fully aware of it before you have traveled the length of a single block in any of these East Side streets, by the whir of a thousand sewing machines, worked at high pressure from earliest dawn till mind and muscle give out together. Every member of the family from the youngest to the oldest bears a hand, shut in the qualmy rooms, where meals are cooked and clothing washed and dried besides, the livelong day. It is not unusual to find a dozen persons–men, women and children–at work in a single room.”

Skilled Labor

Skilled and semiskilled Jewish workers, from increasingly industrialized homelands, continued to arrive in the United States at the turn of the century. Nearly 67 percent of gainfully employed Jewish immigrants who arrived between 1899 and 1914 possessed industrial skills–a much higher proportion than any other incoming national group.

These men and women helped to fill the needs of the expanding garment trades in New York. In 1880, 10 percent of the clothing factories in the United States were in New York City; by 1910 the total had risen t0 47 percent, with Jews constituting 80 percent of the hat and cap makers, 75 percent of the furriers, 68 percent of the tailors, and 60 percent of the milliners.

Jews were also drawn to innumerable other crafts, including bookbinding, watchmaking, cigar making, and tinsmithing, all of which became part of a growing ethnic economy. It has been estimated that only about a third of the heads of families retained their original Eastern European vocations. But almost 2.4 percent moved out of factory work and into self-employment in small businesses at the earliest opportunity. In the virtually all-Jewish Eighth Assembly District, approximating the Tenth Ward, there were 144 groceries, 131 butcher shops, 62 candy stores, 36 bakeries, and 2,440 peddlers and pushcart vendors.

Reprinted with permission from A History of Jews in America, published by Vintage Books.