Wealth, Julius Rosenwald contended, is a blessing and a charge: “I can testify that it is nearly always easier to make $1,000,000 honestly than to dispose of it wisely.”

Born in Springfield, Illinois to German Jewish immigrants in 1862, Rosenwald got his start in the wholesale clothing trade. In 1895 this middling garment salesmen left the family profession to invest in a newfangled mail-order company–Sears, Roebuck.

By 1906, Rosenwald had revolutionized Richard Sears’ catalogue business with clear management goals and innovative organization techniques. It was time to expand. Rosenwald sought a loan from his old friend Henry Goldman. Goldman, later of Goldman Sachs, had a different suggestion–forget the loan and take the company public.

Issuing public stocks in Sears, Roebuck rapidly paid off and in a matter of hours, the market valued Rosenwald’s personal worth at more than four million dollars. Rosenwald’s financial windfall came at a time when most of his employees made less than $16 per week. This inequity was not lost on Rosenwald. As a longstanding member of Temple Sinai, a Reform congregation in Chicago, he looked to his rabbi, Emil Hirsch, for ethical guidance.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Advice from the Rabbi

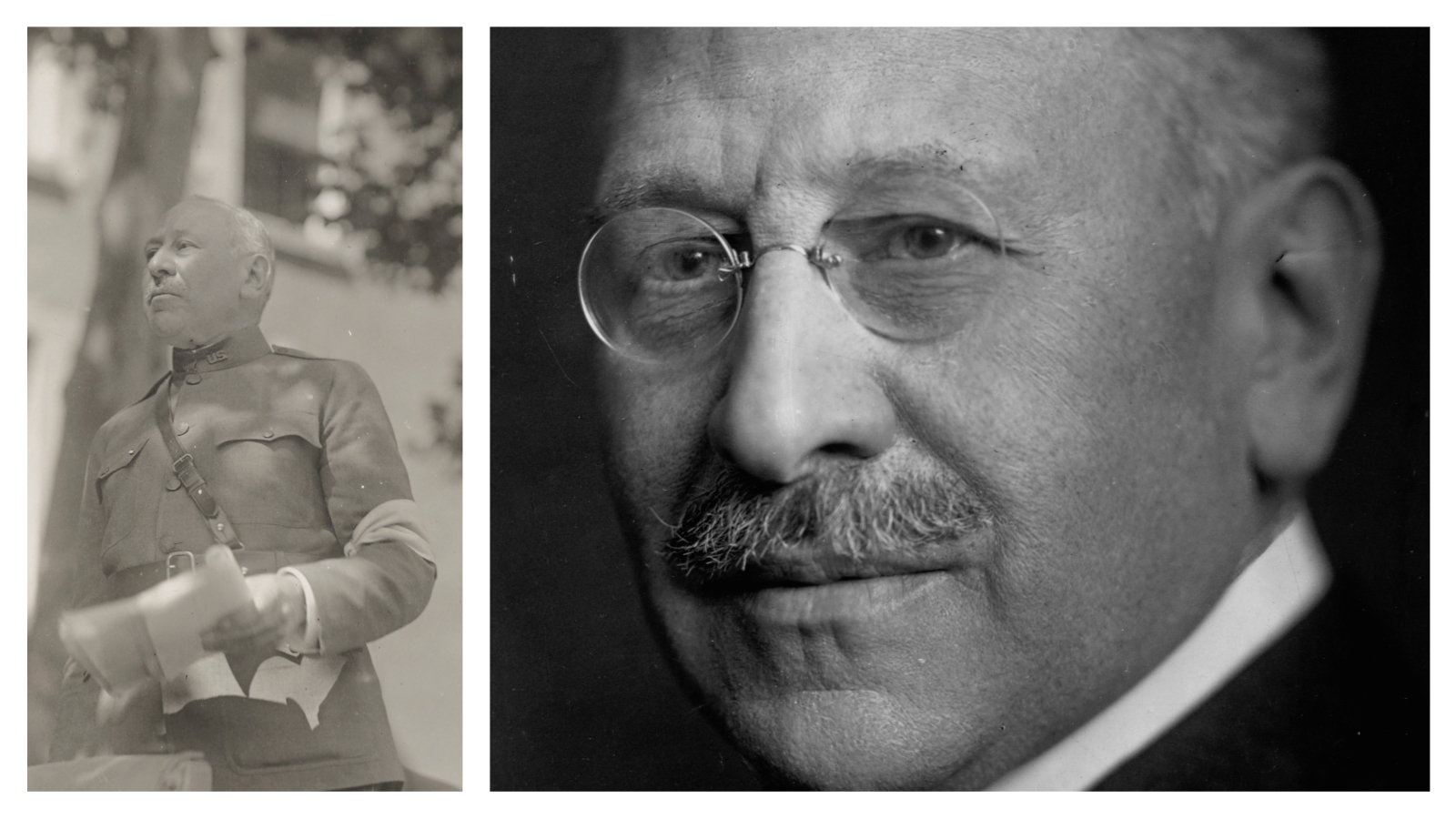

Hirsch, a brilliant linguist and textual scholar, moved fluidly between Jewish and secular academic circles, articulating a vision of Jewish practice beholden to real world concerns. On Yom Kippur in the 1920s, he lectured his congregation with these words: “As long as the weakest in humanity has not his own, civilization is only a sham and a pretender, and as long as civilization is a pretender, Judaism must stand alone as a historic protest against injustice.”

Rosenwald admired Hirsch and quickly absorbed his teachings on Tzedakah. Charity, Hirsch preached, “is not a voluntary concession on the part of the well-situated. It is a right to which the less fortunate are entitled in justice.”

Learning about Jewish ethical guidelines, Rosenwald became aware of Maimonides‘ eight degrees of charity. The highest form of giving, Maimonides claimed, alleviates poverty by offering a method towards self-reliance; a loan or a job, in this model, usually take ethical precedence over alms because jobs and loans can ensure greater dignity and independence for their recipients.

Rosenwald sought to supplement this traditional Jewish approach with modern business practices and progressive ideals. He looked for organizations that were not only filling needs but were doing so in ways that empowered recipients. With donations of needed goods and challenge grants to settlement houses, Jewish organizations, schools, and hospitals, he formed lasting relationships with heralded progressive reformers such as Jane Addams, while establishing a giving model designed to prompt local communities, government officials, and other philanthropists to collectively invest in projects.

Rosenwald & Booker T. Washington

In the spring of 1910, Rosenwald’s philanthropic approach appeared fully formed; he had started to build a legacy funding healthcare, progressive education, and Jewish survival initiatives. Yet that very summer, Rosenwald’s philosophy of giving changed. Upon reading Up From Slavery, Booker T. Washington‘s harrowing autobiography, Rosenwald awoke both to the tragedy of racism and to Washington’s ameliorative efforts at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute.

In October of 1911, Julius, his wife Gussie, and Rabbi Hirsch boarded a private Pullman train headed to sultry Alabama to visit Tuskegee. He was astonished at what he encountered: “I don’t believe there is a white industrial school in America or anywhere that compares to Mr. Washington’s at Tuskegee.” Efficiency, need, and results guided Washington and the industrial departments at Tuskegee.

Rosenwald hankered to get involved and, as usual, started with a small donation of needed items (in this case shoes for the students), before moving on to larger monetary gifts. Eventually, he joined the board, and in 1912, on his 50th birthday, Rosenwald bestowed a grant that would forever secure his philanthropic legacy–a gift to build rural schoolhouses in the South.

Rosenwald had an unusual 50th birthday. He didn’t want balloons, a fancy dinner, or a vacation across the Atlantic. Instead, Rosenwald used the occasion to demonstrate his giving philosophy and set an example for other philanthropists. Rosenwald’s gift marked the beginning of his “Give While You Live” campaign, which he hoped would persuade a new class of wealthy capitalists to give carefully, give often, and give while they are alive.

Give While You Live

Rosenwald’s campaign offered a scathing denouncement of perpetual foundations. In a 1920 article in the Saturday Evening Post he wrote, “I am opposed to the principle of storing up large sums of money for philanthropic uses centuries hence…. The generation which has contributed to the making of a millionaire should also be the one to profit by his generosity.”

Not only did he claim that perpetual foundations fail to honor the obligations to the labor force that secured a philanthropist’s wealth, but he further argued that foundations would devolve into bureaucratic stagnation or irrelevance.

Of all his Give While You Live donations, Rosenwald’s 1912 grant to fund the creation of African-American rural schools across the South most embodied his philanthropic philosophy. The grant required communal participation, with local residents helping to pay for and build the schools.

In The Rosenwald Schools of the American South, Mary Hoffschwelle comments that each school “created a stage upon which many different people could act.” This fledgling grant quickly developed into an amply staffed and funded program. By the 1930s, more than 5,300 Rosenwald schools covered the American South.

Rosenwald didn’t stop there. He began to fund projects organized by Washington’s ideological adversary, W.E.B. Du Bois, who rejected Washington’s belief in accommodation, arguing instead that African-Americans must work to secure legal and political rights. Rosenwald eventually admitted that an education system geared toward industrial education accommodated an unjust racial order and did not advance the long-term aspirations of African-Americans.

Yet instead of choosing sides, Rosenwald continued to assert that it was possible to improve the day-to-day prospects of individuals living in the Jim Crow South with Washington and fully support complete civil rights for African-Americans with Du Bois. He believed his dollars would heal the present and prepare for a just future. In homage to Rosenwald, Du Bois remarked, “He was a great man. But he was no mere philanthropist. He was, rather, the subtle stinging critic of our racial democracy.”

Julius Rosenwald was a dogged philanthropist. He cared little about the posterity of his name while constantly fretting over the daily results of his bequests and actions. “I am certain,” he voiced, “that those who seek by perpetuities to create for themselves a kind of immortality on earth will fail…. Real endowments are not money, but ideas.”

Per the wishes of its founder, who died in 1932, the Julius Rosenwald Fund became the first foundation to deliberately spend all of its endowment. Rosenwald’s legacy rests not in the legal entity of a perpetual foundation but rather in a Jewish giving strategy that prizes efficacy over ego and wisdom over wealth.