Natan Sharansky is a former Soviet dissident and refusenik whose fight for freedom made him a symbol of the repression of Jews under communism and an international icon of the struggle for human rights.

After his 1977 arrest on trumped-up charges of treason and espionage, Sharanky became the face of the global fight for Soviet Jewry, his image plastered on posters held aloft at protests around the world and on the cover of Time magazine. After his release and emigration to Israel in 1986, he became a leader of the Russian-Israeli community and an international symbol of conscience, speaking out about the importance of democracy and human rights.

Sharansky was born Anatoly Scharansky in 1948 to secular Jews in what is now Donetsk, Ukraine. His father, Boris, was a journalist who had served in the Red Army and his mother, Ida, an engineer. Sharansky was a chess prodigy in his youth, a talent he would later credit with helping maintain his sanity through long periods of solitary confinement during which he played games in his head. He earned a degree in mathematics from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology and later went to work for the Oil and Gas Research Institute, a state research laboratory.

Like many Soviet Jews of his generation, Sharansky was almost completely ignorant about Judaism. Theirs was a country that had virtually eliminated organized Jewish life and institutionalized antisemitism, but had also refused to allow its Jewish community to emigrate, often on the flimsy pretext that doing so posed a security threat. In Moscow, Sharansky fell in with a group of Soviet Jews who were secretly studying Hebrew and seeking to emigrate to Israel. On Shabbat, he would congregate with other activists in the street outside the Moscow synagogue.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

But Sharansky also saw his plight as a Jew as inextricable from the larger fight for human rights. He grew close to the dissident physicist Andrei Sakharov, who won the 1975 Nobel Peace Prize for his human rights work, eventually becoming his spokesperson. Along with Sakharov, he was among the founders of the Moscow Helsinki group, which sought to pressure the Soviets to live up to their international obligations to respect fundamental freedoms. “Above all else,” Gal Beckerman wrote in his history of the Soviet Jewry movement, “[Sharansky] believed that asserting his rights as a human being only reinforced what he was claiming for himself as a Jew.”

Learn more about Jews from Ukraine who changed the world.

In October 1973, Sharansky met Natalya (later Avital) Stiglits, whose brother had recently been arrested, at a gathering near the Moscow synagogue. Shortly after, Sharansky applied for an exit visa and was denied, making him officially a refusenik, the term applied to Soviet Jews who had been refused the right to emigrate. The following summer, in advance of a visit to Moscow by U.S. President Richard Nixon, Sharansky was detained, likely out of concern he and other activists would use the visit to draw attention to their cause. While he was being held, Avital’s exit visa was approved, but it was only valid for a week. In the short period between Sharansky’s release and the visa’s expiration, the two married in a private religious ceremony. Avital departed for Israel the following day.

With Avital gone, Sharansky’s activism in the dissident movement grew, and with it the close scrutiny of the KGB. In early March 1977, a full-page article in the newspaper Izvestia falsely accused him and other Jewish activists of espionage. Barely a week later, KGB agents seized Sharansky on the streets of Moscow. Sharansky would ultimately spend nine years in Soviet prison, including more than 400 days in isolation cells and 200 days of hunger strikes, which took a significant and lasting toll on his health. At one point, he weighed just 77 pounds. Meanwhile, from Israel, Avital led a tireless campaign for his release, meeting with top government officials around the world and catapulting herself to celebrity.

The effort would finally yield fruit on the morning of February 11, 1986, when Sharansky was flown from a Soviet prison to East Berlin, where he was to be released in a prisoner exchange. Among the stories told about that day is that Sharansky walked in a zigzag pattern to freedom, a final gesture of defiance of Soviet agents who had ordered him to march straight. At the Glienicke Bridge separating Berlin from Potsdam, Sharansky was met by U.S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Burt and ushered into a waiting Mercedes. He and Avital reunited shortly after in Frankfurt and, by nightfall, he was on the tarmac at Ben Gurion Airport, where Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres embraced him. From there, he was whisked to the Western Wall in Jerusalem where he was carried on the shoulders of hundreds of Israelis.

Sharansky’s first years in Israel were momentous. His first child, Rachel, was born within a year of his arrival. In 1988, Random House published his memoir, Fear No Evil, its title taken from a verse in Psalm 23. Sharansky also quickly emerged as a leader of a Russian-speaking community that had ballooned after the fall of the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet Jews began arriving in Israel, radically transforming the country politically and demographically. Along with another former Soviet dissident, Yuli Edelstein, Sharansky formed a new political party in 1995, Yisrael BaAliyah, which placed immigrant concerns at the forefront of its agenda. In its first electoral showing in the 1996 elections, the party won seven seats and joined the governing coalition. Sharansky became a cabinet minister, leading the Ministry of Industry and Trade.

Sharansky served in the Israeli government for a decade, during which he held a number of positions, including deputy prime minister, minister of the interior and minister of housing and construction. His political career ended in 2006 with his resignation from the Knesset. In the years that followed, he served in a number of prominent positions, most notably chairman of the Jewish Agency for Israel, a position he held from 2009 to 2018.

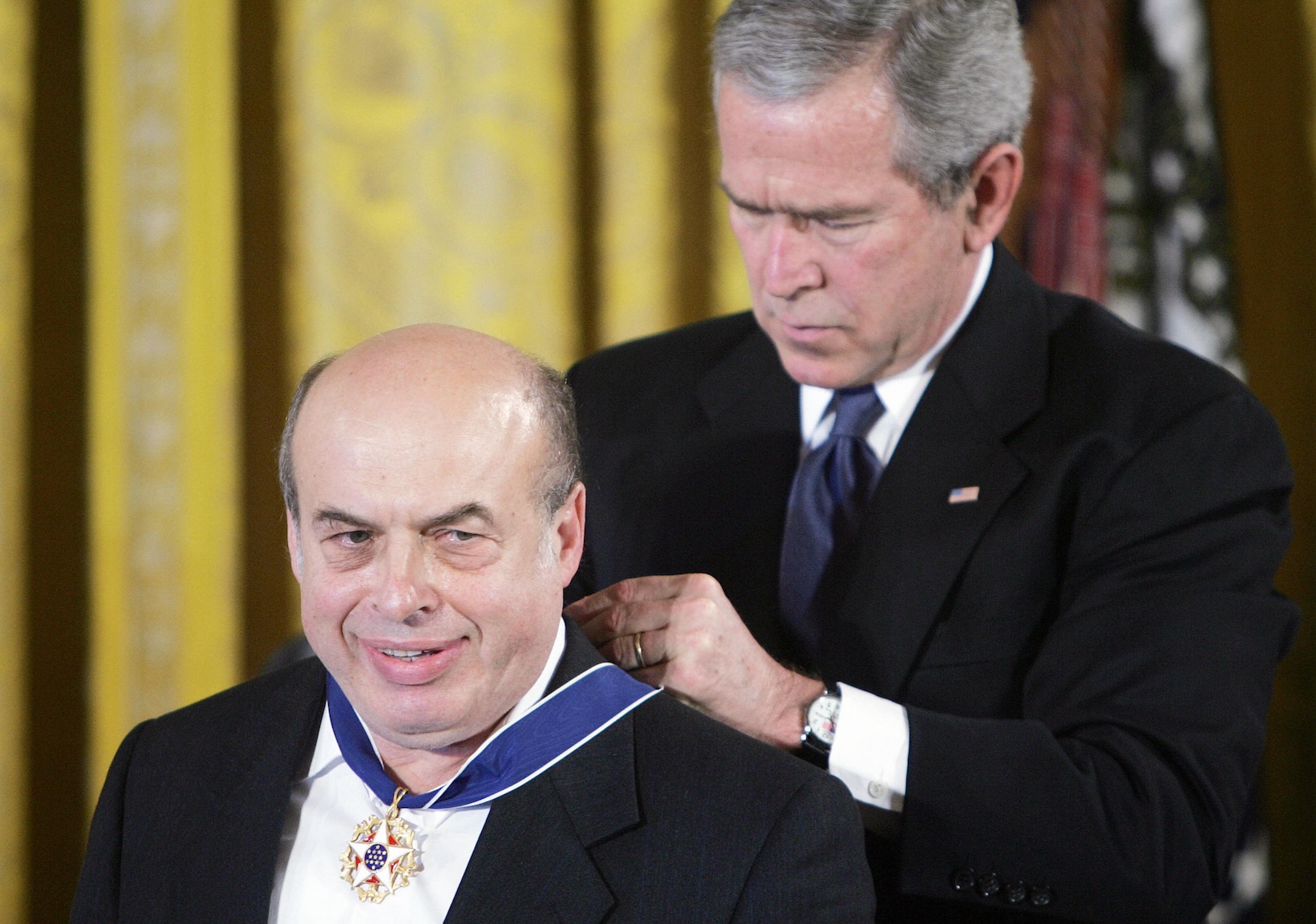

In 2004, Sharansky published The Case for Democracy, which became an international best-seller. The book landed during the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush, who made the promotion of democracy around the world a centerpiece of his foreign policy. Bush invited Sharansky to the Oval Office to discuss the book, which he recommended frequently. In 2006, Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Sharansky has openly criticized Democratic and Republican presidents alike for betraying a tradition of tying American foreign policy to human rights concerns, a coupling he credits with successfully pressuring the Soviet Union on Jewish emigration.