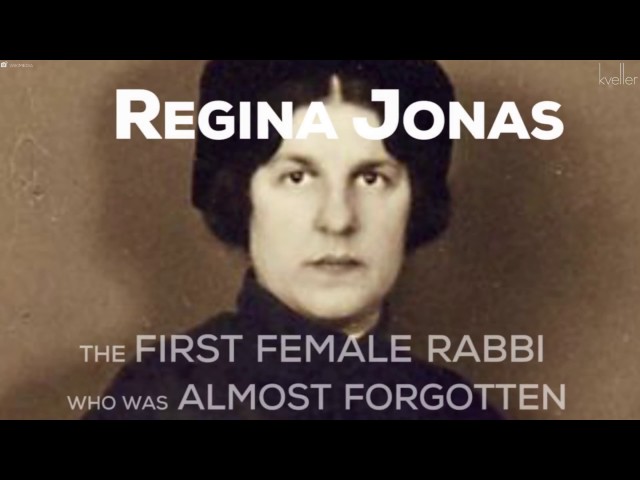

While the movement for women’s ordination was centered in the United States, the first female rabbi was actually ordained in Germany. Regina Jonas (1902-1944) was a 1930 graduate of the Hochschule fur die Wissenschaft des Judenthums (Academy for the Science of Judaism) where she wrote a thesis entitled, “Can A Women Be a Rabbi According to Halachic Sources?” Although her research led to an affirmative answer, the faculty did not unanimously agree. She was subsequently ordained privately by Rabbi Max Dienemann. Jonas worked as a chaplain in various Jewish homes for the elderly and orphanages. After 1942, she served as a pastoral counselor and preacher in the Theresienstadt camp. Jonas perished at Auschwitz.

[Earlier] unrest within the religious Jewish world antedated and prefigured the emergence of Jewish feminism [and the contemporary movement for women’s ordination]. As far back as 1922, we recall, Reform Judaism’s Central Conference of American Rabbis issued a statement favoring the ordination of women. Notwithstanding this resolution, the Hebrew Union College board of governors in 1923 denied ordination to Martha Neumark, who already had completed nearly eight years of study. And in 1939, even the determinedly progressive Stephen Wise balked at ordaining Hadassah Leventhal Lyons, who also had completed her studies at the Jewish Institute of Religion.

Twenty‑three years of further debate within the Reform movement were required before the Hebrew Union College finally succumbed to the pressure of its CCAR alumni and its Union of American Hebrew Congregations, as well as the accumulated moral pressures of the civil‑rights and women’s movements. In 1972, Sally J. Priesand, age 25, was granted ordination.

Nevertheless, the battle for women rabbis was not over. Although Priesand served as assistant rabbi of New York’s Free Synagogue from 1972 to 1977 and as associate rabbi from 1977 to 1978, she encountered innumerable problems in securing her own congregation. For months at a time, the CCAR placement bureau could not so much as arrange an interview for her. Eventually Priesand secured a modest congregation in Tinton Falls, New Jersey.

By then, too, few congregations could be unaware that women were being ordained and granted pastoral assignments in every major branch of Protestantism. By 1982, some fifty women rabbis already had been graduated by the Hebrew Union College and by Philadelphia’s little Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, and almost one‑third of those institutions’ current student bodies were women. Upon ordination, they were finding employment opportunities as educators, chaplains, administrators, pastoral counselors, and increasingly as “associate” rabbis in large congregations and as solo rabbis in smaller ones.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Progress was rather slower within the Conservative movement. In 1971, a group of 13 young women from traditional backgrounds formed a study group, Ezrat Nashim (“Women’s Help” [and also “Women’s Area”, the name for the women’s section in synagogue]). Like their Reform counterparts, they were perturbed by the sexism in Jewish religious law. The following year, several of them barged uninvited into the convention of the Rabbinical Assembly, the collegium of Conservative rabbis, to demand an end to Judaism’s gender bias. Above all, they demanded the right to attend rabbinical school and to receive ordination.

A majority of the rabbis appeared sympathetic. Indeed, over the years, increasing numbers of synagogue boards already had countenanced women’s participation in minyans and in Sabbath readings. In 1973, the Rabbinical Assembly even lent the practices its “official” endorsement. Yet four more years passed without movement on the issue of ordination. In the interval, Jewish women’s study groups were formed to exert pressure on the Assembly. The liberalized practices of individual Conservative synagogues also made their impact.

Finally, in 1978, the Assembly bestirred itself, petitioning the Jewish Theological Seminary to study the ordination issue. The school’s chancellor, Gerson Cohen, responded affirmatively. He appointed a faculty committee, which then conducted a nationwide poll of individual congregations. Two more years passed before the committee members issued their report. The document was favorable.

Even then, the full faculty plenum procrastinated, tabling the issue for yet another year. The professors were by no means blind obscurantists. It was their point, rather, that the essence of Conservative Judaism itself was based on gradualism, that the tradition of the Jewish wife and mother, as sanctified over the millennia, dared not be exposed to as sudden and traumatic a reversal as female ordination.

But in 1981, an exasperated Chancellor Cohen decided to wait no longer. A former Columbia University professor of Judaica, husband of the distinguished Jewish historian Naomi Wiener Cohen, he had long been in the forefront of Conservatism’s progressive wing. With the support of a small group of colleagues, therefore, Cohen established a four‑year program for women with a curriculum identical to that of the rabbinical school. In effect, he was playing shrewd politics, obliging his faculty members to risk future outrage by denying women graduates the privilege of ordination.

None did. In 1983, the faculty voted to accept women into the regular ordination program. A year after that, Amy Eilberg became the first woman to receive ordination at the Jewish Theological Seminary. The great majority of Conservative rabbis and lay people accepted the change calmly. By the end of the decade, a fifth of the Seminary’s student body were women, a dozen had been graduated, and half had secured employment in established congregations, although usually as assistant or associate rabbis.

By then, too, faint tremolos of unrest were apparent even within Orthodoxy. Several rabbis in the trend’s moderate wing contributed articles favoring improved education for women, and in 1979 Yeshiva University’s Stern College for Women added a course in Talmud. In ensuing years, additional women were enrolled at Yeshiva’s Cardozo Law School, until by the mid‑1980s they composed half the student body. The law they studied was not Jewish law, to be sure, and the notion of ordination, even of women’s participation in minyans, was all but unmentionable within the Orthodox tradition. Under fundamentalist pressure, Orthodoxy’s progressive wing actually lost ground in the 1980s. Nevertheless, given the flux of American society, there seemed every likelihood that future confrontations would take place, at least along the margins of Orthodoxy.

Reprinted with permission from A History of the Jews in America (Knopf).