In this chapter, we have already explored many requirements for documents that are meant to prevent forgery. Alas, forgery is common enough, and forgers clever enough, that the list of possible sneaky maneuvers seems endless. On today’s daf, the discussion continues with this rule:

Abaye said: With regard to this one who needs to show his signature in court, he should not show it by writing it at the top of the parchment, lest another person find the parchment and write above the signature that the signatory owes him money — because such a document would be valid, as we learned in a mishnah (Mishnah Bava Batra 10:8): If one presents to a debtor a document in the handwriting of the debtor stating that he owes money to him, the creditor can collect only from unsold property.

When ratifying a document, the rabbinic court must ratify the signatures of each witness. If both witnesses are alive, this is fairly straightforward: Each can attest to their own signature. But if one of the witnesses has died, the court requires two people to testify regarding the signature of the deceased witness. The living witness could theoretically be one of the two who testify to the deceased witness’s handwriting. However, the rabbis were reluctant to hang so much testimony in the ratification process on one person. The solution: the surviving witness can send the court a sample of his own handwriting, which serves evidence rather than testimony. This means the surviving witness is no longer testifying to their own signature. Now, they can join another person to testify about the handwriting of the deceased witness.

While the solution is clever, Abaye is worried about the security of a document that’s merely blank parchment with a signature on it — the ancient equivalent of a blank check. If the witness signs at the bottom, someone could easily scribble an IOU above and, according to the mishnah quoted above, this would stand up in court. Therefore, the recommendation is to sign at the top of the parchment. Since witnesses always sign below the text, there is no room to slip in a forged note.

Did anyone actually try this trick? Apparently so. The Gemara now recounts:

There was a certain Jewish tax collector who came before Abaye and said to him: Let the master show me his signature, as when rabbis come to me and show me it, I let them pass without paying the tax. Abaye showed him his signature at the top of the parchment, though the tax collector kept pulling the parchment away. Abaye said to him: The sages have already anticipated people such as you.

Since rabbis were exempt from certain taxes, and Abaye was one of the most prominent scholars in Babylonia at the time, the tax collector used Abaye’s signature to verify the exemption. However, after requesting that Abaye produce this signature, the apparently unscrupulous tax collector repeatedly yanked at the parchment so as to unroll it further and create space above Abaye’s signature. Abaye assumes that he did so in order to create a space in which to forge a document.

Today’s daf relays several more rulings, each followed by a story in which an attempted forgery is foiled. Thieves are creative; and so must be the laws to keep the public safe.

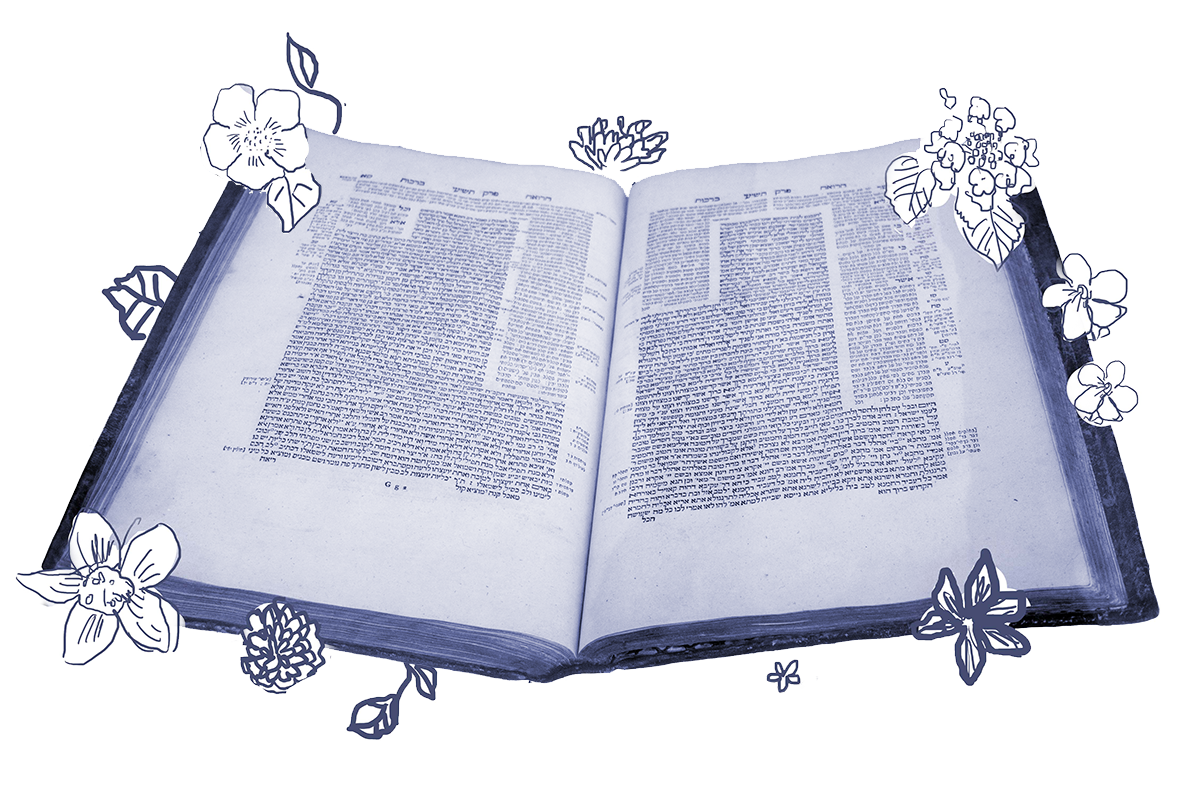

Read all of Bava Batra 167 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on December 9, 2024. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.