Commentary on Parashat Miketz, Genesis 41:1-44:17; Numbers 28:9-15, 7:42-47

On February 11, 1986, Soviet Jewish human rights activist Anatoly Sharansky started his day in the Gulag, where he had been imprisoned for nine years after being convicted on false espionage charges. But thanks to global efforts on his behalf, things that day changed — and fast. KGB agents flew Sharanky to East Berlin where, as news cameras rolled, he crossed the Glienicke bridge to freedom. Reunited with his wife Avital, whom he had not seen for 12 years, Sharansky greeted her with one of the greatest understatements of all time, “Sorry I’m a little late.” He was flown to Israel the same day, greeted by joyful throngs and borne on shoulders to pray at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. The former prisoner, who would take the Hebrew name Natan, would eventually become a leader in Israel and a recognized hero of human rights worldwide.

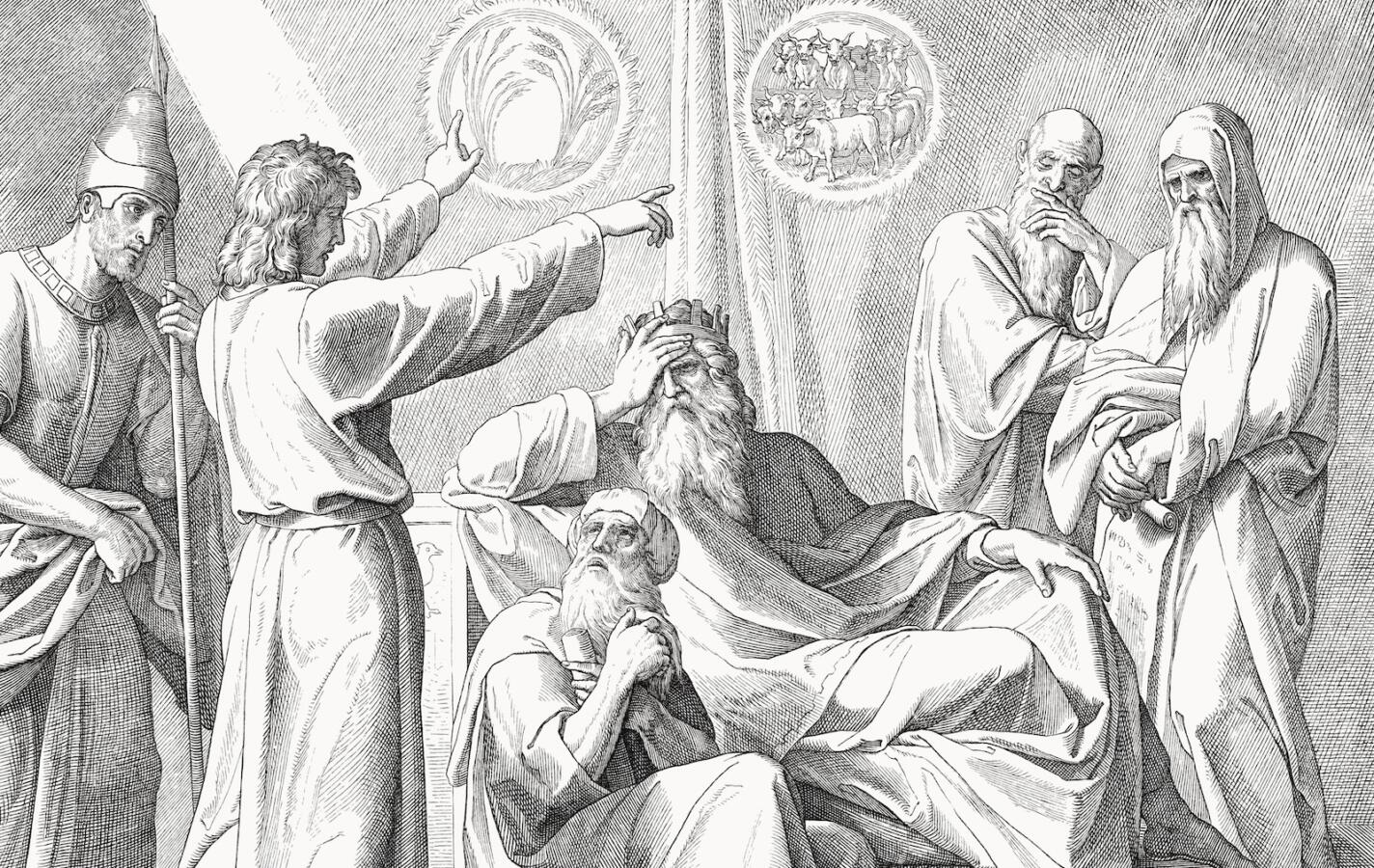

In Parashat Miketz, Joseph experiences a similar scenario: He begins his day as he had for years, in the dungeon where he was imprisoned on false charges. When his reputation as a dream interpreter reaches Pharoah, Joseph is rushed from the jail, given a shave and a change of clothes, and brought before the most powerful man in the world to interpret his disturbing dreams. Joseph explains that Pharaoh’s dreams represent seven years of plenty in Egypt, followed by seven years of famine. While crediting God for his interpretation, Joseph adds that Pharoah should appoint someone discerning and wise to oversee a plan for survival. Sure enough, Pharaoh appoints Joseph, catapulting him overnight from prisoner to second in command of the kingdom. Joseph is given a new name, a wife, and all the trappings of power as he gets to work collecting food for the famine ahead.

Reading the Joseph saga, one marvels at how he always rose to the top. Enslaved by the Egyptian military officer Potiphar, he eventually becomes the supervisor of his estate. Thrown into prison, he is appointed supervisor and caretaker of the other prisoners. No matter where he ends up, Joseph makes the best of his situation and also keeps his moral compass, earning him the later rabbinic epithet Yosef Hatzaddik — Joseph the righteous.

Sharansky, too, kept his mental and moral bearings while in prison. Even though he spent half his time in solitary confinement and over 400 days in a freezing punishment cell, he would later tell reporters, “The years spent in prison, strange as it may seem, are pleasant memories for me. They are memories of years which might have been hard in the physical sense, but, morally, those were pure and bright years, when it was absolutely clear what the good and the evil was, where the light was and where the darkness was.” By contrast, Sharansky explained, the world of public service and government leadership that he entered as a free man was full of moral complexities and ambiguities.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

For Joseph, too, power will bring complexity. In the next Torah portion, he won’t resist the opportunity to effectively make the entire Egyptian population into Pharoah’s serfs. But first, he will face the challenge of forgiveness. This too is part of the transition to leadership after persecution. Upon visiting one of the prisons in which he was held a decade after his release, Sharansky told journalists, “I never saw this fight as a fight with individuals. I saw it as a fight with the system. The system is dead. Do you forgive the people who are dead? Of course, you forgive.” Likewise, South African President Nelson Mandela, who had been imprisoned for 27 years during his struggle against apartheid, famously said, “As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.”

Joseph gives his first son a name that means “forgetting,” signaling that he has forgotten the troubles he endured in his parents’ home. But when his brothers come down to Egypt to procure grain for the family, his trauma is reactivated, and he isn’t in a forgiving frame of mind. The brothers don’t recognize Joseph, who is overcome by emotion when he sees them and overhears them discussing their guilt over what they did to him. At first Joseph tricks and torments his siblings with false accusations. Only in next week’s portion, when Judah delivers a powerful soliloquy declaring his readiness to sacrifice himself for his grieving father and youngest brother, does Joseph accept his brothers’ teshuvah (repentance). His reconciliation with them will be one of the most exemplary paradigms of forgiveness in the Bible, and he will declare that his own suffering has been part of a greater plan to save them all.

Fortunately, most of us won’t undergo the lengthy imprisonment of a Joseph or Natan Sharansky. Neither will we emerge as leaders of a nation or as players on the world stage. But we will face our own challenges. We will have the responsibility to lead in our own spheres while struggling with temptations and moral dilemmas. And at some point, we will face the challenge of finding forgiveness and moving on. The Torah never purports to offer up perfect role models, but it does invite us to consider notable lives lived with courage and growth to inspire us as we live our own.