Commentary on Parashat Bo, Exodus 10:1-13:16

In graduate school, I heard certain new (at least to me) fancy words in every seminar, and no matter how many times I looked them up, I never really understood them: epistemology, hermeneutics, semiotics, heuristics and ontology. But there was one new fancy word I eventually came to understand deeply: multivalence — and it helped me when studying Jewish traditions. Multivalence refers to something having many interpretations and meanings that can co-exist without cancelling each other out.

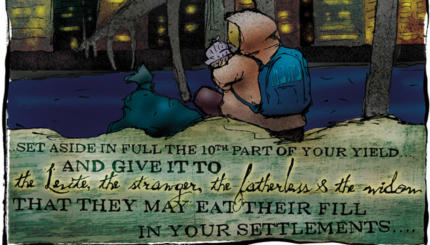

I taught college students in my Introduction to Judaism course about multivalence in preparation for their field work assignment. They had to visit the local synagogue for Shabbat services and to stay around to talk with congregants at lunch. They witnessed practices they had already studied: wearing a kippah or tallit (prayer shawl), praying or reading from Torah. After services, they asked congregants what these practices meant. The students explained that they were not seeking to know how rabbis or Jewish educators would “properly” explain the practice. Through these interviews, they learned that common Jewish practices held multiple meanings for the congregants, both at a given moment and over the course of their lives.Having learned that a Jewish practice could have many, even conflicting meanings, my students would not be surprised, late in the semester, when they learned that verses of Torah are said to have at least 4 levels of meaning (recalled by the acronym PARDeS, meaning orchard) : pshat (the plain meaning), remez (the hinted at or allegorical meaning), drash(the metaphoric meaning) and sod (the hidden meaning). In Parshat Bo, which recounts the final plagues upon Egypt and Pharaoh’s declaration that the Israelites must go, along with Moses’ instructions on how to observe Passover as a commemoration, we get a glimpse of how thoroughly this holiday is characterized by multivalence. In particular, we read about parents offering their children multiple ways of thinking about the holiday.Three times in this parasha, parents are told to instruct their children about the paschal sacrifice, the central rite of Passover. The first time is Exodus 12:26-27: “And when your children ask you, ‘What do you mean by this rite?’ you shall say, ‘It is the Passover sacrifice to the Lord, because God passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when God smote the Egyptians, but saved our houses.” This explanation points to anticipating the departure from Egypt, following the night that the firstborn Israelites are spared when the Egyptian babies are slain. We next encounter a curious child in Exodus 13:8: “And you shall explain to your child on that day, ‘It is because of what the Lord did for me when I went free from Egypt.” This explanation, marching forward in time, anticipates a Passover celebrated by a free people in the land of Canaan, looking back at their relatively recent redemption. The third instance, one that seems projected into a more distant future, follows shortly in Exodus 13:14: “And when, in time to come, your child asks you, saying “What does this mean?’ you shall say, ‘It was with a mighty hand that the Lord brought us out from Egypt, the house of bondage…” This explanation points to Pharaoh’s stubbornness, God’s slaying of the first born sons and beasts in Egypt, and introduces what appears to be a familiar sacrifice practice, one in which Israelite sons are symbolically redeemed.Beyond our parashah, pedagogical preparedness is most lengthily chronicled in Deuteronomy 6:20–25. Here, children ask: “What mean the decrees, laws, and rules that the Lord our God has enjoined upon you?” They are to be told an expansive story that harks back to slavery, one featuring the plagues, the march to freedom, entry into the promised land and culminating in a commandment to observe not just the laws of Passover, but all of God’s instruction.It is unfortunate, I think, that our sages, beginning in the Mishnah and extending to the Passover Haggadah, have often attributed the questions asked about the holiday to four archetypes: a child who is wise, one who is rebellious, one who is simple and one who is silent. This traditional reading has led us to assume that some questions about Passover are more worthy and some explanations are more correct. And it limits the beautiful multivalence of the Torah text.The traditional reading was beautifully challenged visually by the artist Dan Reisinger in the 1982 Passover Haggadah: The Feast of Freedom. In that image, each child is made of torn paper of a different color. Inside each of the four silhouettes, there are extra heads, torsos and legs made of the colors of the other three children. In other words, each person contains composite parts of all the others, a strong visual midrash, suggesting that because we are complex people, we — just like the congregants my students spoke with — will always be finding new understandings of how and why Passover is meaningful to us.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.