Many of the serious messages of are encoded in word play and irony, and the Book of Esther‘s seemingly absent God is no exception. The centrality of the concept of hester panim or “the concealed face of God” to Purim is recognized in the fact that Esther is the only text in the Hebrew Bible, except for the Song of Songs,that does not mention the name of God explicitly.

In the case of Purim, hester panim’s importance is also intimated by the name of the heroine of the central narrative of the festival, Esther. The Babylonian tractate Hullin 139B states, “From where does the bring the name Esther? From the verse ‘But I [God] will surely conceal my face [“haster astir panai“] on that day for all of the ill that they have done — for they turned to other gods. (Deuteronomy 31:18).'” The name Esther is interpreted as an extension of the phrase for a “concealed God.”

Discussing the verse in Deuteronomy, the medieval commentator Abraham ibn Ezra suggests that the term “turned to” or panah should actually be read as “whored with” or zanah. Here, the blame for the broken relationship between God and Israel lies squarely with Israel’s assimilation and worship amongst the gods of the nations, a circumstance apparent in the story of Purim as well. There seems to be no distinction between Esther or Mordechai and the non-Jewish Persians until the Jews themselves reveal who they are.

Furthermore, Esther’s moniker is doubly ironic, because her name is a Hebraization of the name of the Near Eastern goddess Ishtar, and her Uncle Mordechai’s name is a Hebrew version of the name of the Near Eastern god Marduk. Through the lens of a nitty-gritty melodrama of sex, deception, and violence, the Book of Esther openly critiques the possibility of a “secular” world of blind fate and challenges the nature of assimilated Jewish life. Without God at its center, Jewish life and Jewish heroes merely become a poor imitation of the world around them. The Diaspora Jews depicted at Purim’s core can be seen as a fulfillment of biblical prophecy of divine abandonment resulting from Jewish assimilation to the cultural norms counter to a Jewish center.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Esther as Commentary

The Book of Esther as a whole may be a kind of or meditation on the verse in Deuteronomy cited above. This meditation is far from simple, much closer to a hall of mirrors than an opportunity for focusing reflection on any one proper identity or image. Culturally in the Book of Esther, Jews mirror non-Jews, going so far as to popularize the names of foreign gods for their own elite. This is a dramatic turn for a Jewish people told to be a nation holy like God throughout the period of their growth in the desert (Leviticus 19: 1-2) or for that matter, for humanity as a whole, which is said to be created in the image of God in the first chapters of Genesis.

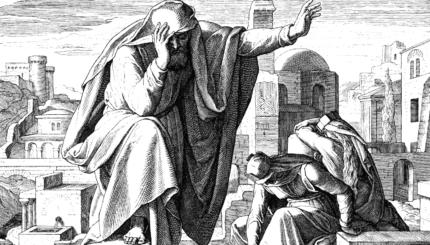

Yet despite God’s vow in Deuteronomy, it is not clear if the Jewish disconnect with the divine in Esther is the result of God’s withdrawal from protection of Jewish religious sanctity during the destruction of the First Temple–from which Mordechai and Esther’s ancestors as said to have fled–or if God withdraws from the Jews only gradually because of their assimilation in Persia. Whether God or the Jewish people initiate the break in this relationship, the result is that the Jews can no longer mirror God because God is no longer a face to be experienced and reflected upon. The world of the Jews of the Purim story is one of physical and spiritual exile.

Purim and the Day of Atonement

Amidst practices of drinking and bawdy entertainment, Purim contains a serious undercurrent that carries the responsibility of repentance to mend a broken relationship with the divine. Jewish teachers note that etymologically, Purim is partnered with Yom HaKippurim, the Day of Atonement. Yom HaKippurim is said to be a day k’purim — a day like Purim. This linguistic and thematic connection reflects on the tone of both days, giving a sense of life’s random absurdity and Purim a feeling that even the most outrageous celebrants are in fact approaching the work of reconciliation with God. The terminology of the hurt and concealed face provides a particularly strong link between these two festivals.

The concept of the concealed face appears initially when Adam and Eve hide themselves “from the face of God” after eating from the Tree of Knowledge (Genesis 3:8). Then, as part of his punishment following Cain’s murder of his brother Abel, God asks Cain, “Why has your face fallen?” (Genesis 4:6). Having admitted his guilt, Cain summarizes his punishment: “Here, you drive me away from the face of the soil, and from your face must I conceal myself” (Genesis 4:14). The concealed face represents a violent rift between people and God, a burden of great wrong that is an ancient, shared vocabulary of pain and disappointment.

Furthering the link between repentance, God’s concealed face, and Purim, another medieval commentator, Nachmanides, notes that the curse of God’s concealed face in Deuteronomy — to which Esther is most likely related — is a burden of the sin of idolatry punishable by exile, not relieved until the Jewish people demonstrate profound remorse through vidui [confession] and teshuvah [repentance]. These are terms essential to the ritual process of reconciliation between people and the divine on Yom HaKippurim. While Purim theology is by its nature at turns serious and ridiculous, the link between Purim and unfulfilled atonement makes thematic sense.

As social commentary on the cause of the concealed face of God, the Book of Esther challenges both Jewish and divine identity from numerous directions. Purim can be understood as a ritualized celebration of breaking down day-to-day persona and identity by questioning the old and trying on the new. The festival also presents the deeper conflict of Jews who do not know who they really are in relation to their own culture, the surrounding culture, or their Creator. Indeed, even the identity of God, certainly the hero of the Hebrew Bible, is challenged. God does not make even a cameo appearance in the Book of Esther — at least not in a form to which the text cares to give a name.

While it is not clear that Esther and Mordechai fully internalize the lessons of transforming danger and fear into a productive model for a lasting partnership with God, there are indications of a move towards a kind resolution — or at least resolve — as the narrative concludes. Esther’s decree to establish permanent feasting, gifts to the poor, and the sending of portions to neighbors to commemorate the events of her day (Esther 9:22) is done in a language of commandment generally reserved for the divine. This may indicate her desire for reestablishment of a commandment-based community, thus inviting God to reconnect with the Jews on terms God can understand. It may also suggest that Jewish leadership has matured enough to take on the mantel of providing religious commandments and political and social balance for the Jewish people in a period of God’s lasting absence.