Although the biblical references to Shavuot and its early history revolved around an agricultural festival and making offerings in the Temple (particularly grain offerings), the festival is now more closely associated with commemorating the time the Israelites received the Torah while wandering in the wilderness.

The agricultural roots of the holiday are evident in Sefirat HaOmer, the counting of the omer, which refers to a measure of grain that was brought to the Temple on . The counting of the omer–a literal enumeration of what day it is in the omer — begins on the second night of Passover and includes seven weeks of seven days, with the 50th day being Shavuot. The counting occurs during the (evening) service.

During the omer period, it is customary to study one chapter of the tractate Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) every afternoon, although some communities continue to study it throughout the summer.

Some of the customs associated with Shavuot display remnants of the agricultural tradition. Synagogues are often decorated with flowers and foliage. This is also connected with Mishnah Rosh Hashanah (a section of the Talmud), which states that Shavuot is the judgment day for fruit trees. Recent customs are to plant flowers around the synagogue on the day before Shavuot. Sometimes grass is spread on the floor of the synagogue, a custom related to the agricultural aspects of this festival or to remind the people of the grass upon which the Israelites stood while receiving the . In Israeli agricultural communities, some people dress in white and ride on carts filled with the produce of the late spring harvest.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

There is general feeling of sadness from Passover to Shavuot. There are a number of theories for why Jews view this period with sadness, one of which refers to a plague that killed many students of the famed talmudic sage Rabbi Akiva during this period. Whatever the reason, it is a time of semi-mourning when traditional Jews do not perform wedding ceremonies, cut their hair, or attend live musical performances. The period of sadness is interrupted on the 33rd day of the counting of the Omer, on Lag B’Omer (the Hebrew letters “lamed” and “gimmel” which spell “lag” add up to 33). Some traditional Jews end the semi-mourning period on this day, and some continue it after that day until three days before Shavuot. The main Ashkenazic (Eastern European) Orthodox custom is to mourn from Passover until three days before Shavuot with the exceptions of Lag B’Omer, Rosh Hodesh (the new moon) for the month of Iyar, Rosh Hodesh for the month of Sivan, (and for many) the fifth of Iyar (Israeli Independence Day).

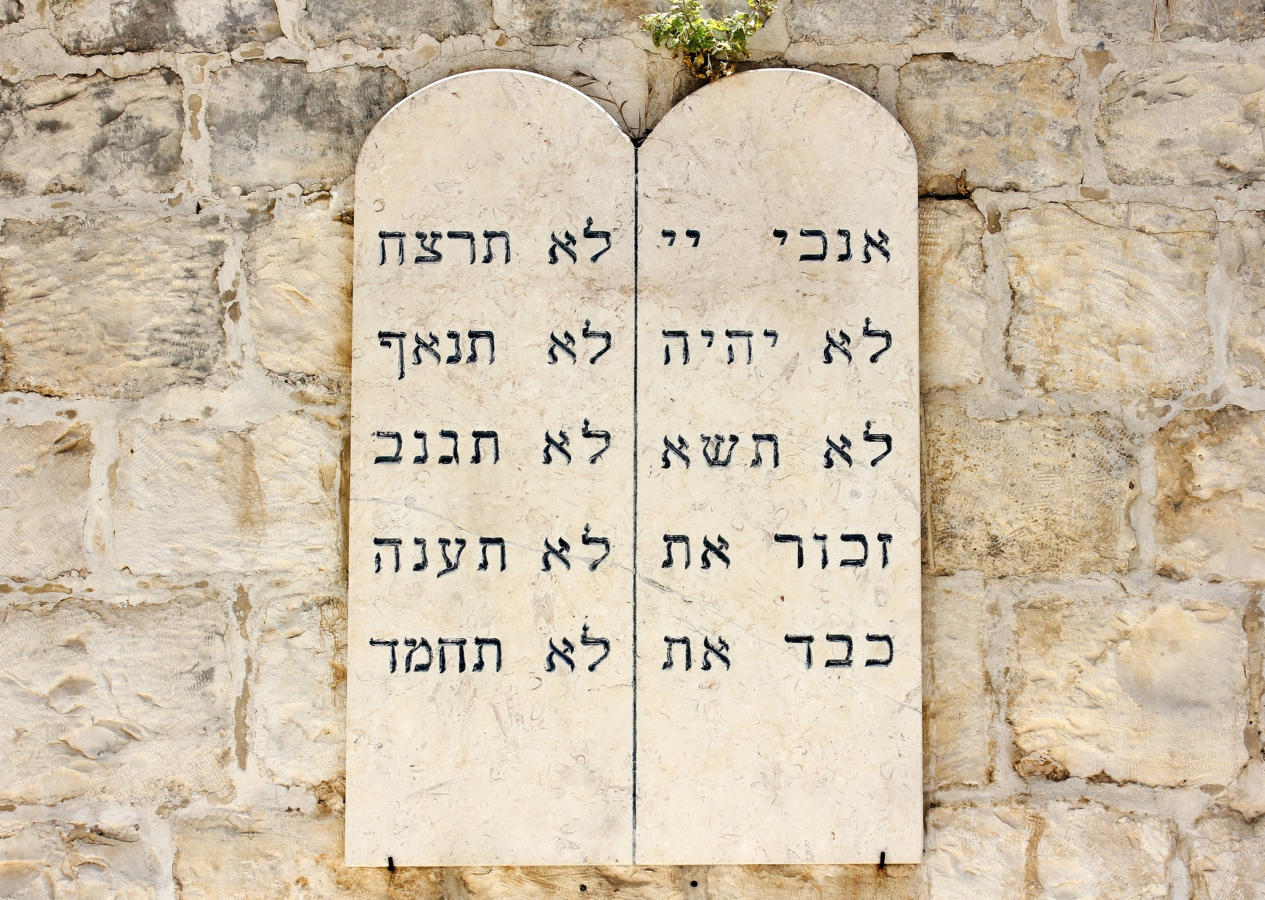

It is customary to begin the evening service of Shavuot a little later than usual — after darkness has fully fallen — in order to be certain that the 49th day of the counting is completed. A long-standing custom for Shavuot is to stay awake all night and study. There are a few reasons for this, among them the legend that the Israelites mistakenly fell asleep on the night before receiving the Ten Commandments. There is a traditional agenda for the study called “Tikkun Leil Shavuot” (preparation for Shavuot), which includes excerpts from all of Jewish sacred writings.

For those who observe two days of Shavuot, there are two Torah scrolls read on each day. The first scroll of the first day is Exodus 19 and 20 about the giving of the Ten Commandments. The second scroll is Numbers 28, describing the festival of Shavuot. The traditional Haftarah (prophetic reading) is Ezekiel 1 and 3 containing the prophet’s vision of God. Reform Jews who celebrate one day of Shavuot also read from Exodus 19 and 20, but prefer an excerpt from Isaiah 42 for the Haftarah. It speaks of God’s people teaching the “true way” to the nations. The first Torah reading for the second day is Deuteronomy 15 and 16, which among other things describes the pilgrimage festivals. The second reading is the same as the first day. The Haftarah is from Habakkuk 2 and 3 and mentions the revelation at Sinai.

Shavuot liturgy is also distinctive for including two Aramaic “piyyutim” (medieval poems) that were meant to strengthen the people’s faith during the Crusades. Akdamut, written by 11th-century Rabbi Meir, who lived in Worms, Germany, is usually recited before the first Torah blessing. Yatziv Pitgam–a poem of praise and a prayer for protection written by Rabbenu Tam (1110-1171)–is read on the second day. A full Hallel (Psalms of praise) is said on both days of Shavuot.

Another distinctive part of Shavuot worship is the reading of the scroll of Ruth, traditionally read on the second day of the holiday. One reason for the association between Ruth and Shavuot is that that the story opens during harvest, which is when Shavuot falls.

As on other pilgrimage festivals, Yizkor is recited after the Torah reading on the second day for traditional Jews and on the first day for Reform Jews. A modern addition to the holiday in liberal Judaism is Confirmation, a ceremony for 15 or 16 year olds, confirming their life-long commitment to Judaism and Torah study.

Pesach

Pronounced: PAY-sakh, also PEH-sakh. Origin: Hebrew, the holiday of Passover.