On the morning of September 28, 2000, a six-member Likud delegation led by the then-leader of the Israeli opposition, Ariel Sharon, paid a visit to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. From the moment the plans for the visit had been made public four days earlier, there was concern among Israeli security officials that the heavily media-covered visit might inflame some Palestinian nationalist sentiments because it would be viewed as a deliberately provocative symbol of Israeli control of all of Jerusalem, east and west.

These concerns prompted consultations on the matter between Israeli and Palestinian officials, culminating in a telephone conversation between Israeli Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben-Ami and the head of the Palestinian Preventive Security Organization, Jibril Rajoub, in which Rajoub indicated, “If Mr. Sharon refrains from entering the Mosques on Temple Mount, there will not be any problem.” Only then did the Israeli police agree to permit the visit–along with a 1,500 member police escort, just in case.

A Match in a Tinderbox

Sharon’s visit was relatively brief, avoiding the mosques. It was completed by 8:30 a.m. and was followed by a vocal demonstration of about 1,000 Palestinians led by Israeli Arab Knesset members who hurled stones at Israeli policemen. But this too was relatively brief and not unprecedented in the context of previous Palestinian-Israeli clashes in that religiously and emotionally charged area of Jerusalem. By the afternoon, despite sporadic flare-ups of further clashes between police and demonstrators, Israeli security officials concluded that the matter was behind them.

They turned out to be seriously wrong.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Within hours, the Voice of Palestine was broadcasting denunciations. Sharon was said to have conducted “a serious step against Muslim holy places.” Yasser Arafat, the Palestinian Authority chairman, called upon the entire Arab and Islamic world to “move immediately to stop these aggressions and Israeli practices against holy Jerusalem.” Repeated broadcasts throughout the evening and night described the visit as a deliberate defilement of the mosques.

By the morning of September 29, Palestinian public opinion was inflamed in a way that Israeli intelligence had failed to predict. In the West Bank town of Qalqilya a Palestinian police officer participating in a joint security patrol with Israeli police opened fire and killed his Israeli counterpart, leading to the permanent suspension of all joint Israeli-Palestinian security patrols. Following Friday morning prayers in the mosques on the Temple Mount, hundreds of Palestinians rushed past Israeli border guards toward the platform overlooking the Western Wall plaza where Jewish worshippers were praying prior to the holiday.

When heavy rocks began raining down from the compound on the Mount onto Jewish worshippers in the plaza below, the Israeli border guard contingent opened fire on the Palestinian rioters with rubber bullets, killing four and wounding more than 100 persons. The second Intifada had been sparked with its first casualties. More than 1,100 Israelis and 5,500 Palestinians were been killed in the conflagration.

The appellation Intifada–which means resurgence in Arabic–was almost universally applied to the violence that erupted in the year 2000 as if it were a continuation of the Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip from 1988 until 1992. But the differences between the two rapidly became clear. Where the first Intifada was characterized most memorably by Palestinian youths throwing stones at Israeli soldiers, the second Intifada was far bloodier, taking on the aspects of armed conflict, guerilla warfare, and terrorist attacks. The stone-armed Palestinian child of 1990 was replaced by the armed adult fighter of 2000.

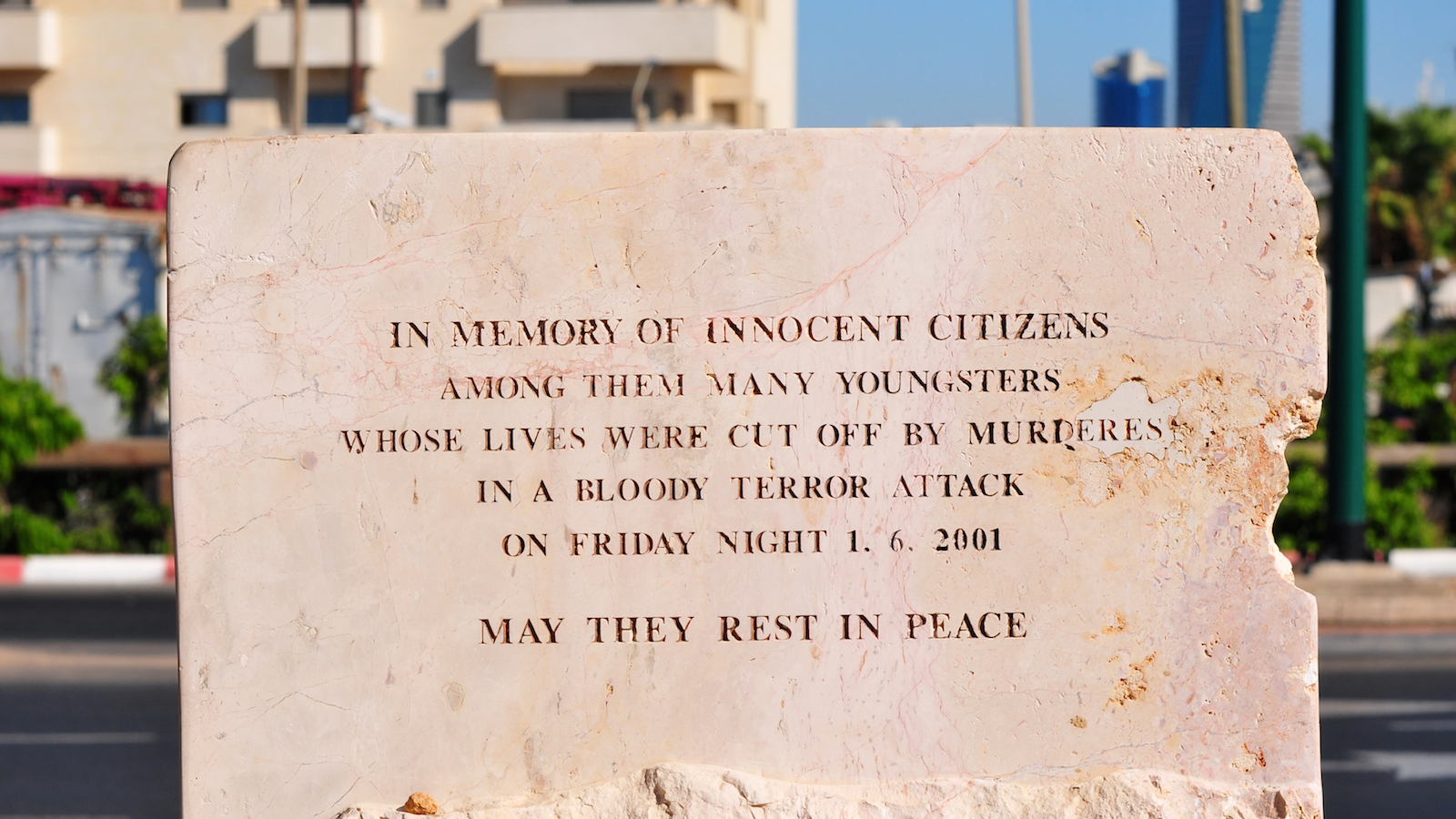

Exploding Buses and Rocket Attacks in Israel’s Center

The Israeli civilian population knew of the first Intifada mainly from televised pictures and stories brought home by soldiers. But the second Intifada brought fear home to the streets of Israeli towns in the form of exploding buses and rocket attacks. It dealt a grievous blow to the entire Israeli political left, which had been associated with and supportive of the peace process.

As in many other aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian confrontation, there are conflicting claims, analyses, and narratives surrounding the question of what sparked the second Intifada, who fueled the confrontation, what strategic aims it was supposed to serve, where it was headed, and even what it should be called. Any understanding of the issues, however, must begin with historical context, including the major events affecting the Middle East conflict over the past decade: the Oslo agreements, the Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon, the attempt to negotiate an end to the conflict at Camp David in July 2000, and the post-September 11 atmosphere in the United States.

From Oslo to Camp David

The official and almost unanimous Palestinian position on what Palestinians call the Al-Aksa Intifada–named after a mosque on the Temple Mount–is that it was a spontaneous and authentic outpouring of pent-up Palestinian wrath at the continuing Israeli occupation of their lands, which finally erupted when sparked by Sharon’s provocative tour of the Temple Mount. According to this narrative, the signing of the Oslo agreement between Israel and the PLO on September 13, 1993, gave the Palestinian people hope that they would shortly see Israeli settlements dismantled, their economic condition dramatically improved, and their flag raised in a sovereign State of Palestine in all of the Gaza Strip and West Bank.

Seven years later, Israeli settlements had only expanded, the average Palestinian was mired deeper in poverty than before, and the Palestinian Authority–not state–controlled a disappointing less than half of the West Bank. When the Camp David summit meeting of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, U.S. President Bill Clinton, and Arafat in July 2000 failed to conclude an agreement leading to the creation of a Palestinian state, the Palestinian public mood dropped to new lows of despair and heights of anger.

There is no doubt that opinion polls among the Palestinian population registered over a long period of time growing dismay at the dissonance between the perceptions of where the Oslo process was supposed to lead to and the harsher realities of life in the Palestinian Authority. By the summer of 2000, even Israeli intelligence reports were warning of the possibility of broad and violent Palestinian riots if the Camp David summit failed to live up to expectations.

At the time, not a few media commentators noted with some surprise the relative calm that prevailed for a full two months between the failure of the Camp David summit and Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount. The high number of casualties that marked the initial days of the second Intifada–much higher than the comparable numbers in the first Intifada–was shocking to the Palestinian public. Palestinians then suffered tremendously as the second Intifada progressed, paying a high price in lives. Their freedom of movement in the West Bank and Gaza was extremely curtailed by Israeli troops, and a severe economic crisis and widespread unemployment made the Palestinian economic situation on the eve of the Intifada appear rosy in comparison. However, every indicator showed continued Palestinian support for continuing the armed conflict with Israel.

The Israeli View

The Israeli perspective is more skeptical of the claim that Sharon’s visit sparked a spontaneous reaction that got out of hand. Starting at least three years prior to the eruption of the second Intifada, Israeli military intelligence followed with growing concern certain indicators of trouble to come: increasingly militant Palestinian broadcasts, the establishment of military training camps, excessive growth in the number of Palestinian armed forces beyond that permitted by the Oslo agreements, a lack of attempts by Palestinian authorities to confiscate illegal weapons, and frequent releases of terrorist detainees from Palestinian prisons.

Based on these facts, the Israel Defense Forces prepared comprehensive contingency plans for the possibility of an armed confrontation with Palestinians, including heavily fortifying its positions. In the first days of October 2000 these plans proved their worth in reducing Israeli casualties to a minimum. This contrasted sharply with large numbers of Palestinian casualties–many of them sadly civilian and caused by the fact that the Palestinian population initially understood the renewed call for an Intifada as a summoning to the stone-throwing mass demonstrations of the first Intifada.

What Went Wrong?

But the second Intifada rapidly took on the characteristics of armed combat between Israeli and Palestinian forces–with the Palestinian civilian demonstrators caught in the middle of the deadly cross-fire. The discrepancies between Israeli and Palestinian casualties, however, only served to fuel further Palestinian anger and desire to continue the fight.

While the Palestinians saw the Camp David summit as a failure on the part of Israel to make a serious diplomatic move toward them, Israelis regarded the offer made by their negotiators as extremely generous. Barak had proposed creating a Palestinian state in 96 percent of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, dismantling most Israeli settlements, and dividing sovereignty in Jerusalem. The fact that Palestinian leaders dismissed the offer out of hand and that the Palestinian side did not even make a counter-offer–as documented in memoirs by Israeli and American negotiators–and that for many Israelis the Palestinian ‘response’ appeared to be an armed conflict, has done more to harm the Israeli peace movement than any other event in decades, as many left-leaning Israelis became disillusioned with the peace process.

The second article in the series explores the continuation of the Intifada.