As Israel shifts from a “melting pot” model to one of multiculturalism, Israeli Jews are bringing their once marginalized culture back to the center of Israeli life.

“Mizrahi” is a socio-political term describing Jews from Arab and/or Muslim lands, including Jews from North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the Caucasus. The Ashkenazic establishment in Israel coined the term in the 1950s in response to the large wave of immigrants from Arab countries at that time. The immigrants soon began to use the term to describe themselves as well. “Mizrahi” is distinct from, but often overlaps with, the term, “Sephardi,” and the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

While “Sephardim” literally means Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, it has expanded to describe Jews from Africa or Asia, or to describe those who follow , as opposed to Ashkenazic, religious practice. Following the expulsion from Spain, many Sephardic Jews immigrated to Arab countries, where they blended with the local population, making it difficult to distinguish between Sephardim and native Mizrahim.

Since the expulsion of Jews from Spain in the late 15th century, Sephardim and Jews from Arab lands (some who had returned to Israel from Babylonia, now Iraq, during the Second Temple period), were the majority of Jews in the land of Israel, and Sephardic religious practice dominated Jewish life. But beginning in the 1880s, Russian, Polish, and German Jews (all considered Ashkenazic Jews) immigrated to Israel in large numbers.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The Ashkenazim soon became the majority of Jews in Israel, and by 1948 they were 80% of the Jewish population of Israel. Due to their larger numbers, and because modern Zionism, for the most part, originated in Europe, the Ashkenazim became the leaders of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine. When Israel declared independence in 1948, Sephardim and Jews from Arab lands were almost entirely absent in positions of leadership.

Mizrahi Jews Return to Israel

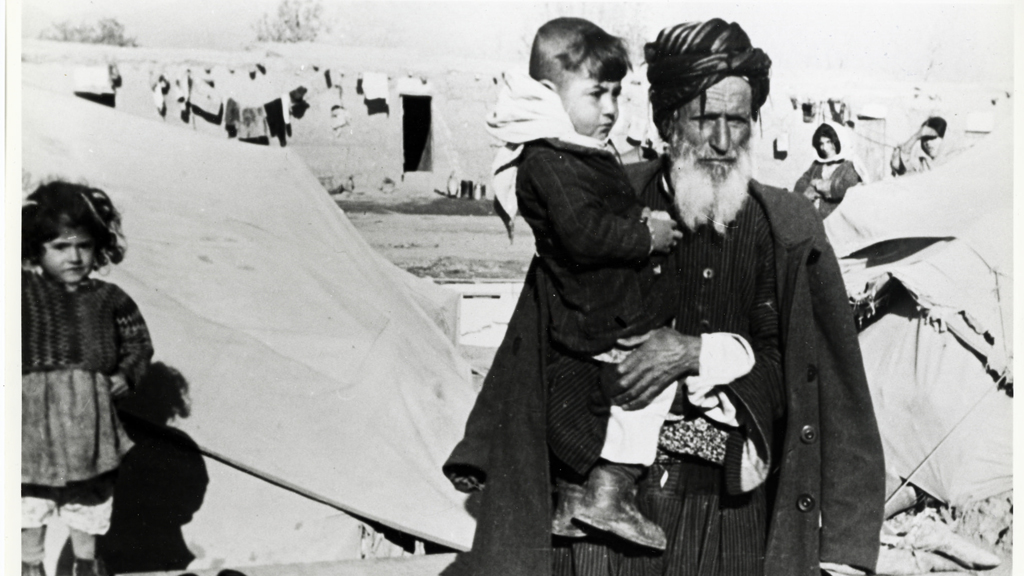

Following Independence, as Arab violence forced them to leave their native countries, Mizrahim began to arrive in Israel in huge numbers. The Ashkenazic establishment saw these newcomers as backward “orientals” whose traditions and culture were similar to that of Israel’s enemies, the Arabs, and so Mizrahim were victims of systematic discrimination. Upon arrival in Israel, Mizrahim were sent to transit camps, where living conditions were very difficult. When they moved out of the camps, they were settled in Israel’s least developed neighborhoods.

In Israel’s version of the “melting pot,” Mizrahim were encouraged to conform to the Western Ashkenazic Zionist ideal, mainly via the public schools and the army. Young Mizrahim studied Ashkenazic heritage and historical figures and, in the public religious schools, prayed and practiced Judaism according to Ashkenazic customs. The attitude of David Ben Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, was typical of the Ashkenazic leadership in the early years of the state: “Those [Jews] from Morocco had no education. Their customs are those of Arabs…The culture of Morocco I would not like to have here…We don’t want Israelis to become Arabs.”

Israel’s Black Panthers

The Ashkenazic establishment’s efforts to “modernize” Mizrahim, however, were largely unsuccessful, and Mizrahim retained their unique culture and strong identity. By the early 1970s, Mizrahim made up half of Israel’s population, but still were absent from the country’s leadership structure and were far poorer, as a whole, than Ashkenazim. Mizrahi protests against the Ashkenazic establishment intensified with the Black Panthers. Modeled after the American Black Power movement, the Black Panthers were a radical political group of Mizrahim who fought for Mizrahi civil rights.

Beginning in 1971, thousands of young Mizrahim took to the streets to protest, mostly in Jerusalem. Although the movement disintegrated after only two years and never became a viable political party, it succeeded in bringing discrimination against Mizrahim into the public discourse. Two of its leaders, Sa’adia Marciano and Charlie Biton, went on to serve in the representing other left-wing parties.

The Black Panther movement is also credited with helping to bring Israeli Prime Minister Menahem Begin to power in 1977, breaking the hegemony of the Labor party that represented secular Ashkenazic Zionist ideology. Although Begin was Ashkenazic, the Mizrahi vote enabled him to topple the Labor party that had been in control of Israeli politics since the beginning of the state. In his campaign, Begin appealed to Mizrahim by portraying himself as a humble and pious person with socially conservative and economically liberal values, who would change the status quo that had been established by the Ashkenazic socialist elite.

Mizrahi Jews Today

Today, Mizrahim remain significantly poorer than Ashkenazim in Israel. Many still live in the same development towns where they settled in the 1950s and 1960s, and work blue collar jobs.

But the role of Mizrahim in Israeli society is changing. Mizrahim now hold positions of power in the Israeli government and army, although these institutions are still dominated by Ashkenazim. Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the former Sephardic chief rabbi of Israel, has run a widely publicized campaign on both religious and political fronts to restore power to Sephardim, a term which he uses in the larger, religious sense to include Mizrahim. Rav Ovadia’s religious campaign, whose motto is to “restore the crown to its rightful place,” strives to restore Sephardic halakhah (Jewish law) and minhag (custom) to its former centrality in Israel, where it had dominated Jewish life for hundreds of years.

Rav Ovadia is also the spiritual leader of the Sephardic ultra-Orthodox party, Shas, whose main constituents are secular Mizrahim, mostly Morroccan. Shas has had significant political success, often controlling several seats in the 120-member Knesset, but, perhaps more importantly, the party has set up a vast network of schools and social services that promote Sephardic culture. For a monthly fee that is smaller than that of public schools, Shas schools, which are partially funded by the state and partially funded by the party’s private funds, provide a school day that is three hours longer than standard, hot lunches, transportation, education in the Sephardic tradition, and numerous social programs for the students’ families.

The Third Generation

The third generation of Mizrahim in Israel, those born in the 1970s whose parents and grandparents immigrated to Israel with the large wave of immigration in the 1950s, has mixed feelings toward its Mizrahi identity. For many, the lines between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim are blurring. Mizrahim and Ashkenazim, for the most part, study together, are enlisted together in the army, and often marry one another.

The younger generation of Mizrahim often does not understand why the older generation sees Mizrahi culture as such a central part of their identity. Many argue that the unique Mizrahi culture is being replaced by a uniform Israeli culture based on Jewish religion and nationalism, Hebrew culture, and certain local behavior and ethics.

Some young Mizrahim, however, are reclaiming their Mizrahi heritage. Nonprofit organizations such as Mi-Mizrah Shemesh work to empower Mizrahi youth and teach them about their heritage. Publications such as Tehudot Zehut: Ha-Dor ha-Shlishi Kotev Mizrahit (Identity Impact: The Third Generation Writes Mizrahi) give voice to the third generation’s unique experience of being Mizrahi. Young Mizrahim are also fighting to transform the nation’s public schools, where Ashkenazim and Mizrahim study together, by bringing Mizrahi history and culture into the classroom alongside Ashkenazic.

Their vision is not one of Mizrahi dominance, like that of the Shas school system, but of different cultures co-existing. They hope that these efforts will ensure that the fourth generation of Mizrahim in Israel will see their heritage, not as a stumbling block, but as a source of pride.