The Jews of Ethiopia—known as the Beta Israel—have experienced a long history of famine, religious oppression, and civil war. But in the 20th century the community went through some major changes as it was transplanted into Israel.

In 1974, following a coup d’etat, Ethiopia came under the Marxist-Leninist dictatorship of Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam. Under Mariam’s regime, anti-Semitism rose, and physical conditions worsened for the Beta Israel, with starvation across the country.

In May 1977, Israeli President Menachem Begin started selling arms to Mariam’s government, hoping to secure freedom for Ethiopia’s Jews. Later that year, Israel took 200 Jews out of Ethiopia on a plane that had emptied its arms cargo for Mariam’s use. Mariam agreed to the airlift—given his reliance on Israel’s arms, he could hardly refuse.

Operations Moses and Solomon

Between 1977 and 1984, a total of 8,000 Ethiopian Jews came to Israel in a number of small airlifts, all authorized, albeit grudgingly, by the Ethiopian government. Large-scale started in 1984 with Operation Moses, a mission that brought 8,000 Jews to Israel in just a few months. The operation, which began in November, 1984, ended prematurely in January 1985 when news of the airlift reached Ethiopia’s Arab allies.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In March 1985, another 650 Jews were rescued in Operation Joshua, but approximately 15,000 Beta Israel still remained in Ethiopia, many of them elderly, sick, or weak.

The final and most dramatic large-scale operation was Operation Solomon. 14,325 Beta Israel were airlifted to Israel in 36 hours on May 24 -25, 1991 amid political turmoil that forced Mariam to flee the country.

By the end of 1991, only a handful of Beta Israel remained in Ethiopia, although many thousands of Falasha Mura, whose Jewish identity has been disputed, still remain today.

Problems Arise

While the operations that brought about Beta Israel’s exodus were dramatic and swift, integration into Israeli society has been painstakingly slow. Even today, the Ethiopian Jewish community in Israel is still grappling with problems: they are marginalized socially, religiously, geographically and professionally.

When they first arrived, housing was often provided in mobile homes located in Israel’s peripheral areas. Housing conditions were regularly squalid, inadequately heated in the winter or cooled in the summer. Ethiopians were isolated and disempowered, with children far from decent schools. Life in an industrialized, modern society baffled many of the older community members, and adjusting to simple things like electricity was often difficult.

Israelis were not always quick to help make the transition easier. For example, Yehuda Dominitz, then Director General of the Jewish Agency’s Department of Immigration and Absorption, declared in 1980 that, “[taking] a Falasha out of his village, it’s like taking a fish out of water…I’m not in favor of bringing them [to Israel].”

Religiously, life was also complicated. Although their Jewish status had been affirmed back in the 16th century by North African scholar Radbaz and again by leading Jewish figures of the 20th century, there were still many who doubted the authenticity of the community’s Jewish status and practice.

When the first waves of immigrants arrived, the Beta Israel were forced by the Israeli Rabbinate to undergo a symbolic renewal of their Jewish identity by immersion in a (ritual bath).Although no one argued that this was undertaken in order to convert the community, this practice, known as hidush hayihud, literally the “renewal of the unique,” was seen by many Beta Israel community members as humiliating and unnecessary. The practice was eventually abolished in 1985 following a month-long strike of the Ethiopian Jewish workforce in Israel.

Integrating into Israeli Life

Slowly, change began to take place. In 1993, a program created by the Ministry of Absorption encouraged immigrants to buy housing in more central areas such as Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Although it happened gradually, by 2001, more than 10,000 Ethiopian immigrants had taken advantage of the program and purchased homes, although mostly not in the areas the government originally intended. Still, temporary housing has become largely a thing of the past.

Slowly, change began to take place. In 1993, a program created by the Ministry of Absorption encouraged immigrants to buy housing in more central areas such as Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Although it happened gradually, by 2001, more than 10,000 Ethiopian immigrants had taken advantage of the program and purchased homes, although mostly not in the areas the government originally intended. Still, temporary housing has become largely a thing of the past.

The government also worked to cut unemployment.In 1999, 53% of Ethiopian immigrants aged 25-54 were employed, compared with 76% in the general Israeli population. Today unemployment rates are still significantly higher in this community than among any other Jewish Israeli group, but the statistics are beginning to look better. This improvement has been achieved by introducing back-to-work training schemes tailored to suit the community, improving education for Ethiopian school-age children, and moving Ethiopian families to centers of employment.

Despite the government’s mission to bring the Ethiopian community to Israel and attempts to combat racism both in the workplace and at large, discrimination continues to be an issue. .One event, known in Israel simply as the “blood scandal,” revealed that Israel’s Emergency Ambulance Services, Adom, had routinely been dumping donations of Ethiopian blood on the assumption that it was likely to be tainted with HIV. When the Israeli newspaper Maariv broke the story in 1996, there was national outrage and the policy, ongoing for a number of years, was overturned.

Although there have been many improvements to their quality of life, many Ethiopians still feel that the Israeli government has let them down by denying mass immigration to the Falasha Mura community still in Ethiopia.

With all of these issues, certain aspects of Ethiopian life have definitely improved. Ethiopian culture is becoming increasingly understood and cherished in Israel. Ethiopian restaurants are now more common, and Ethiopian music has become more influential, helped by bands such as the hugely successful Idan Raichel Project that has incorporated Ethiopian vocals, rhythms, and lyrics.

Organizations such as The Israel Association for Ethiopian Jews have been working to empower the community through grassroots efforts and political lobbying.

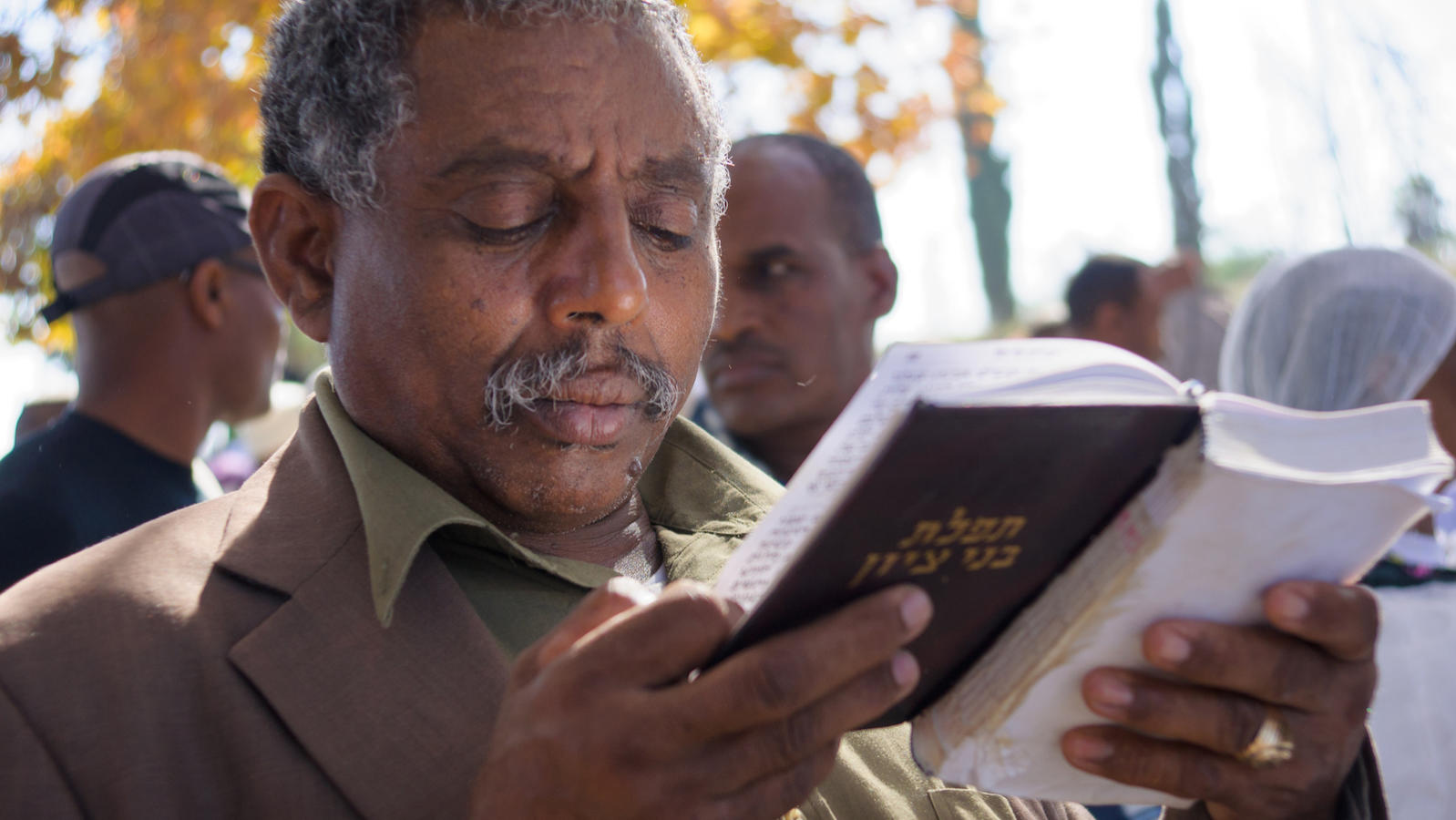

Thanks to their involvement, the Ethiopian Jewish festival of Sigd became an official state holiday in July 2008. As in Ethiopia, the community celebrates this festival by fasting, reading from the (Bible), and feasting in celebration of their renewed acceptance of Jewish law.

Although all Israelis do not celebrate Sigd, those who do must be given the day off by their employers. The recognition of this holiday by the Israeli is a sign of improving attitudes towards the Ethiopian community and its Jewish practices.

Although the place of the Ethiopian community in Israel is becoming more established, full integration is far from complete. Like with any immigrant group, the older generation has found integration more difficult.

The gap between the generations has also meant that youth often need to guide their parents and grandparents through everyday life in Israel. This overthrows the accepted model of family life in Ethiopia, where elders were always revered and consulted. Inter-generational breakdown continues to be a huge challenge to this fragile community, and rising levels of crime among youth might be, partially, a by-product of this collapse.

And yet, there’s great hope in Israel that through continued lobbying, specialized government training and education programs, and sensitivity within individual communities, the Ethiopian community, an estimated 120,000 strong in 2011, will feel increasingly confident and at home in the Jewish state. This, while simultaneously retaining the unique heritage they brought from centuries of Jewish life in Ethiopia.