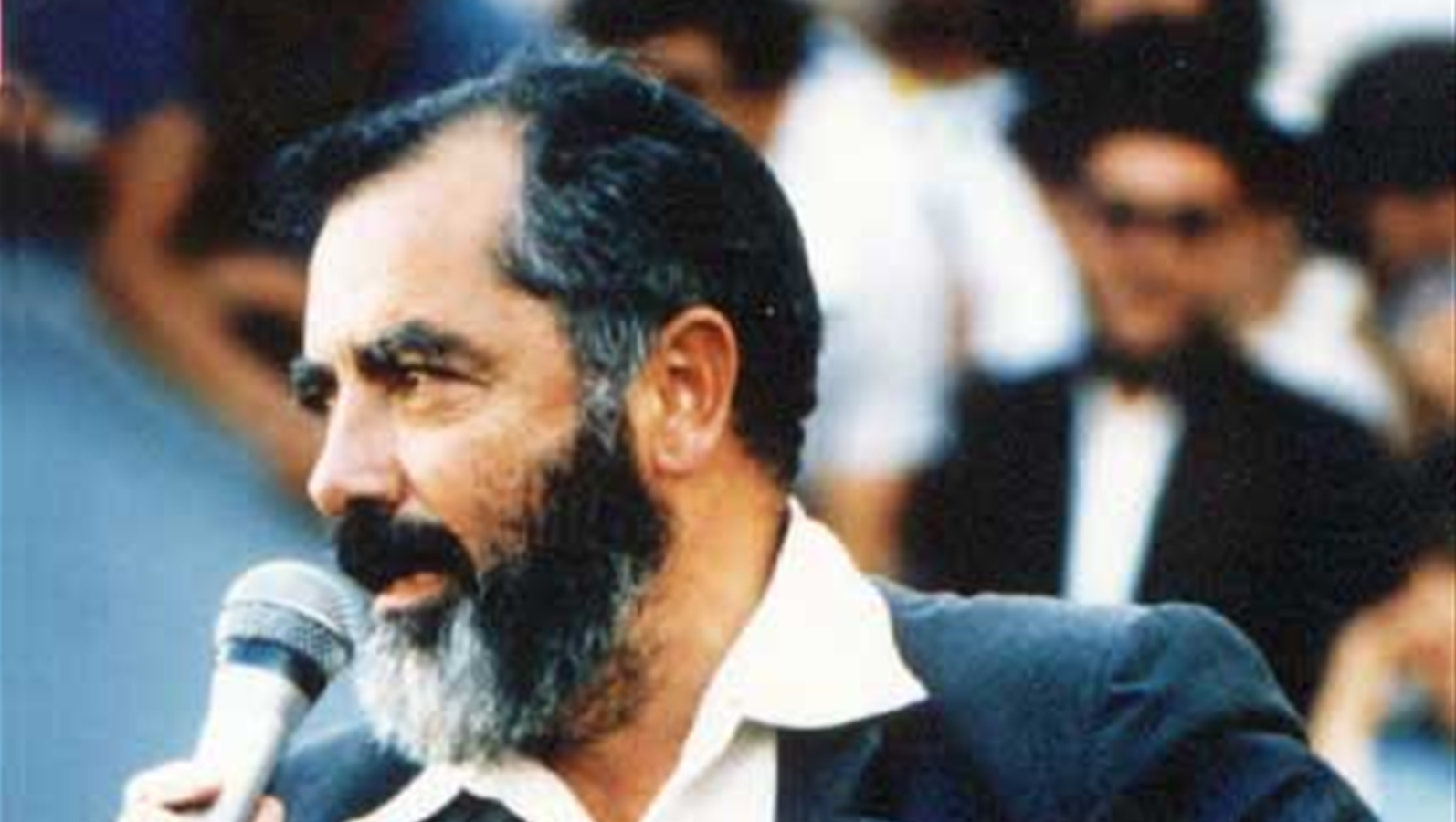

Perhaps no name is more synonymous with the Jewish radical religious right than Meir Kahane. Born in Brooklyn in 1932, and assassinated in Manhattan in 1990, Kahane’s lasting infamy came mainly from two projects: founding the Jewish Defense League in America and forming Kach, the political party under which he would eventually run for — and win — public office in Israel.

Early Life

Kahane was raised in a traditional Orthodox home where radical politics were common conversation. His father was a strong advocate of militant Zionism, with positions informed by Ze’ev Jabotinsky‘s revisionist Zionist school. Jabotinsky’s politics spoke to central features of the Kahane family’s history: Five of their relatives were killed in a 1938 ambush by anti-Zionist Arabs, and another flank of the Kahane clan perished in the Holocaust.

In 1946, Meir joined Betar, Jabotinsky’s youth movement. Kahane did not shirk from the group’s illegal activities. In one early episode, he was arrested in New York City for pelting British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin with vegetables in protest of Bevin’s anti-Zionist stance.

The First Steps

After receiving rabbinic ordination in 1957, Kahane worked as a pulpit rabbi at a small Conservative congregation in Queens. He was fired in 1960 over religious differences. Kahane soon found work with the Orthodox-oriented Jewish Press. He published partisan editorials, often warning Jews of a coming holocaust at the hands of inner-city Blacks or Hispanics. Through his writing, Kahane achieved modest fame in the New York Jewish world.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

During this period, Kahane also moonlighted with the FBI, assuming a false identity to infiltrate the ultra-conservative John Birch Society. And as the student protest movement intensified in 1965, he worked to cultivate pro-Vietnam War sentiment on American college campuses. In 1968 Kahane and his longtime friend Joseph Churba released the book The Jewish Stake in Vietnam.

Kahane believed that the John Birch Society was notoriously anti-Semitic, and that the Vietnam War was a must-win Cold War quagmire that would determine American strength and Israel’s future. So, Kahane explained, his disparate activities were actually united in their aim to protect Jewry in America and abroad.

Still, Kahane was largely unknown outside of Jewish world until he founded the Jewish Defense League (JDL) in 1968.

Formed in New York City, the JDL proclaimed its commitment to “protect Jews from anti-Semitism by whatever means necessary.” Using “Never Again” as a rallying cry, the JDL ran small-scale, sometimes thuggish patrols in changing New York City neighborhoods, where elderly and impoverished Jews faced anti-Semitism, robberies, and harassment.

As the JDL grew wealthier and attracted more devotees, its operations became more ambitious. Though still small in ranks, the League bombed numerous Arab and Soviet targets in the United States between 1968 and 1971, including the New York offices of the Soviet airline Aeroflot, a Soviet cultural building in Washington, and even a Russian gift shop in Minnesota.

These stints attracted global attention. Kahane became a known name, and through his extremist activities he gained some supporters, and even more detractors, worldwide.

Naturally, the League drew ire from the American government, which was fearful that Kahane would foil the détente that had only recently been achieved in US-Soviet relations. By 1970, the FBI was monitoring JDL phone calls.

Born to Be Wild

There is little doubt that Kahane was drawn to the infamy of heading a terrorist organization. In The False Prophet, a 1990 biography of Kahane, journalist Robert Freedman writes that the rabbi founded the JDL in an effort to create “…a movement important enough to satisfy his rampant ego.”

This work also allowed Kahane to indulge his vices. From his prominent position Kahane enjoyed extra-marital affairs, and — Freedman has convincingly argued — embezzled fundraised dollars. Though he styled himself as a modest devotee to Jewish causes, it is difficult to ignore the immense personal benefit Kahane enjoyed by cultivating himself as a divisive and controversial public figure.

Kahane managed to dodge legal sanction for years, but by 1971 he faced a de facto ultimatum: leave the United States or face the possibility of criminal prosecution. So Kahane and his family moved to Israel.

From Outlaw to Lawmaker

Once in Israel, Kahane formed the Kach political party in 1971 and channeled his efforts into the parliamentary system. He preached that the state could find security only by aligning its political and social spheres with Jewish law. Guided by an apocalyptic outlook, he openly spoke of the imminent arrival of the Messiah.

Kahane decried the secular Zionism that he found prevalent in Israel, once stating: “I live in this country because it is an obligation ordered by God. Otherwise, why would I want to live in a country which, from my point of view, is miserable and uninteresting?”

His rhetoric focused most of all on evicting the Arab population of Israel, and he spoke freely of the impossibility of maintaining a Jewish democratic state in the face of a growing Arab minority.

The End to a Legacy

In 1984, Kahane was elected to a term in Knesset, polling just more than 25,000 votes (1.2 percent of those cast). His tenure was short-lived, and Kach never held more than one seat, or made any substantive legislative impact. Before the 1988 election, an amendment to Israel’s Basic Laws was passed, barring any candidate whose platform “incited racism,” a more-or-less direct reference to Kahane’s platform. Ever a marginal character, Kahane once again found himself with relatively few followers, but with much media attention.

Blacklisted from Israel’s political establishment, Kahane continued to make public appearances around the world until he was assassinated at a Manhattan speaking engagement in 1990. The prime suspect, El Sayyid Nosair, an Egyptian with connections to Al-Qaeda, was ultimately convicted. After Kahane’s assassination, his son Binyamin formed a splinter party, Kahane Chai (“Kahane Lives”), which was likewise barred from participating in the 1992 Israeli election. Binyamin was killed in a terrorist ambush in 2000 near the West Bank settlement of Ofra.

In his later interviews, Meir Kahane strove to paint himself as a martyr. But for the most part, the mainstream has not dealt kindly with him. In the 1980s, the American Jewish Committee published a pamphlet calling him a “quasi-fascist,” the Anti-Defamation League decried his activities in print, and the FBI, which had once employed him as an agent, monitored him.

Perhaps Kahane’s most enduring legacy is his writing; he authored several books including the bestseller They Must Go, about what he considered the “problem” of the growing Arab minority in Israel. He continued to publish in the Jewish Press until his death.

Though the JDL and Kach never collected as many supporters as other right-wing Jewish organizations of the 20th century, such as the settler group Gush Emunim, Kahane made sure he was on the collective Jewish mind for two decades. And radical as he was, Kahane’s blend of dogmatism and violence provided an identity for thousands of dissatisfied Jews around the world.