When death occurs, Jewish law demands that immediate plans be made for burial. This is in accord with the ancient belief that it was a great dishonor and disrespect not to inter the dead. Making funeral plans serves as a necessary activity for the mourner at the beginning of the grief process. The mourner reaffirms his concern for the dead through actions which serve at the same time to overcome his wish for identification and incorporation with the lost loved one. The onen [a mourner from the time of death through the funeral] through his actions experiences the fact that he is “not dead,” not still and lifeless, as he may consciously or unconsciously feel or wish himself to be.

During this first period of grief there is an intense desire on the part of the bereaved to do whatever he can for the departed. Jewish tradition meets this need by placing the responsibility for all the funeral arrangements on the mourner, not by shielding and excusing him from these tasks. It even releases the onen from the obligation to perform any positive religious commandments, which on all the other days of his life are binding, so that he may devote himself instead to these burial preparations and arrangements.

Facing the Reality of Death

A funeral according to halacha [Jewish law] emphasizes that death is death. Realism and simplicity are the characteristics of the Jewish burial. In this respect it stands in clear contrast to the American funeral ritual, which, as Dr. Vivian Rakoff has said, “is constructed in such a way as to deny all the most obvious implications.” Such modern American customs as viewing the body, cosmetics, elaborate pillowed and satined coffins, and green artificial carpeting that shields the mourners from seeing the raw earth of the grave are all ways in which the culture enables us to avoid confronting the reality of death.

Other associated practices such as sedating the mourners, hurrying them away from the grave, and keeping children away from the cemetery are part of the same pattern and are to be deplored. They only serve to reinforce feelings of unreality: “This isn’t really happening” or “He isn’t really dead.” Whenever American Jews adopt such customs they cheat themselves of the valuable and healing grief work that is built into the Jewish funeral. “The disservice that the modern funeral’s denial of death does to the surviving families and the rightness of expressing grief in passionate form should be publicized and explained.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Dealing With Ambivalence and Unresolved Grief

The simplicity of the Jewish burial averts another psychological pitfall. The religious prescription for plain, unadorned, simple coffins and for the avoidance of ostentation in the funeral itself serves as a deterrent to the excessive expenditure of family funds for irrational reasons. This expense is often the way that the family represses its guilt over past treatment of the dead or defends itself against its feelings of anger because the loved one has abandoned them. These feelings need to be worked through as a normal part of the process of grief so that later the memories of the deceased can be enjoyed without pain or avoidance. The working through of ambivalent feelings toward the dead by members of the family is extremely important in order to avoid later psychosomatic damage.

I have myself conducted therapeutic interviews with such people, suffering from various forms of cancer and ulcerative colitis, in which the onset of the disease could be traced to a time shortly after a traumatic loss that had somehow not been fully faced up to and resolved. In each case the patient displayed ambivalence and unresolved grief. For example, a woman in her late sixties was admitted to the hospital with severe abdominal pains for which no physiological cause could be found. A preliminary psychiatric consultation indicated that she was severely depressed but assumed that it was simply because of her advancing age and her excessive dependency needs.

But my conversation with her elicited the fact that she had not attended the funeral of her daughter who had died of cancer four years before. She had never confronted the reality of her daughter’s death, and she felt somehow that God was punishing her because she had not gone to the funeral. Her pain was, in her mind, His punishment for what she had not done then. When we began the grief work and she spilled forth her guilt and her anger at her daughter for leaving her by dying, her physical symptoms began to subside and she was soon able to return home. She was still in some pain but it was now recognized for what it was, emotional pain, and therapy became helpful. Her rabbi agreed to help her continue working through her long-delayed expression of grief, and she soon recovered.

In a much more tragic case that I know, a 28-year-old man refused to permit a lifesaving operation to be performed in order to stop the spread of his cancer. His two-year-old only son had died just three months before of leukemia, and the father’s grief was so overwhelming and his identification with his son was so complete that he no longer wished to live. His body heeded his mind’s demands, and he died soon after.

Tangibly Expressing Anger and Sorrow

The most striking Jewish expression of grief is the rending of garments by the mourner prior to the funeral service. The rending is an opportunity for psychological relief. It allows the mourner to give vent to his pent-up anger and anguish by means of a controlled, religiously sanctioned act of destruction.

Kriah, the tearing of clothes, is a visible, dramatic symbol of the internal tearing asunder that the mourner feels in his relationship with the deceased. Even after the shiva is over, the garments may never be completely mended but must show the external scar of the internally healing wound. Reminders such as these constantly elicit grief reactions even as the mourner slowly begins to take up the pattern of everyday living.

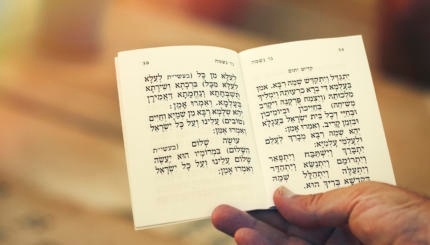

Judaism opposes repression of the emotions and enjoins the mourner to express his grief and sorrow openly. In the funeral itself there are several signals for the full outpouring of grief. The eulogy is intended to make the mourner aware of what he has lost. Traditionally, its function was to awaken tears. The familiar pattern of prayer now has a heartrending newness, as the El male rachamim [God, full of compassion], heard so many times before, is recited this time with the name of the dead for the first time. At the cemetery the recitation of the Kaddish [prayer recited in memory of the dead] stirs the memories of all who have mourned, and they join in collective sorrow together with the newly bereaved to affirm God’s will and glory.

The raw, gaping hole in the earth, open to receive the coffin, is symbol of the raw emptiness of the mourner at this moment of final separation. Burying the dead by actually doing some of the shoveling themselves helps the mourners and the mourning community to ease the pain of parting by performing one last act of love and concern. What more familial and poignant act is there than that of “putting to rest” as children are put to rest at night by their parents. I have seen mourners standing simply transfixed as cemetery workers callously filled in the hole until they could bear it no more and tore the shovels from their hands to finish the burial themselves.

Excerpted with permission from “The Psychological Wisdom of the Law” in Jewish Reflections on Death, edited by Jack Riemer (Schocken Books).

Sign up for a Journey Through Grief & Mourning: Whether you have lost a loved one recently or just want to learn the basics of Jewish mourning rituals, this 8-part email series will guide you through everything you need to know and help you feel supported and comforted at a difficult time.

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.