Death is the great equalizer. The rabbis were quite concerned that the rituals and objects of Jewish burial indicate the fact that every human being is created equal and every human being is equal in death. This notion of democracy in death is illustrated best by the following quotation from the Talmud, Moed Katan 27 a-b:

Formerly, they used to bring food to the house of mourning: the rich in baskets of gold and silver; the poor in baskets of willow twigs. The poor felt ashamed. Therefore, a law was established that all should use baskets of willow twigs… Formerly, they used to bring out the deceased for burial: the rich on a tall state bed, ornamented and covered with rich coverlets; the poor on a plain bier. The poor felt ashamed. Therefore, a law was established that all should be brought out on a plain bier…

Formerly, the expense of the burial was harder to bear by the family than the death itself, so that sometimes they fled to escape the expense. This was so until Rabban Gamliel insisted that he be buried in a plain linen shroud instead of costly garments. And since then we follow the principle of burial in a simple manner.

Judaism is also concerned that the body return to the earth as soon as possible. “For you are dust, and unto dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:19). This value is reflected in the preference within Jewish law for a simple casket (aron) constructed of wood. Wood naturally decomposes while a metal casket would prevent the body from “returning” to the earth. Although metal nails and handles may theoretically be used, traditional caskets use wooden pegs, the interior is unlined, and some have four holes in the bottom that allow the body to come into contact with the earth.

The type of wood used in the casket is not important. In some areas, a “plain pine box” is used; in others, a redwood casket is common. The wood may be polished or natural. Sometimes, a wooden Magen David (Star of David) is attached to the top of the coffin.

The choice of coffin is often a task that causes emotional reaction among the bereaved. Most large funeral homes have a “casket room,” a display area filled with the variety of available coffins. For many, walking into this room brings the bereaved into stark confrontation with the reality of death facing them. For some, it can be a terribly disconcerting experience. For others, it brings a sense of peace and relief. Whatever the reaction, it is a task that must be done.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Rabbinic authorities recommend the selection of the simplest of caskets, both to reflect the value of democracy in death and to avoid unnecessary expense. The range in cost of caskets is extraordinary–it ranges from several hundred to thousands of dollars. It is preferable to donate monies to tzedakah [charity] rather than to spend it on lavish caskets.

Traditionally, nothing is buried with the body in the casket except for some earth from Israel, the Holy Land, and the person’s tallit [prayer shawl].However, some families ask to bury small mementos, such as photos or letters, with the deceased.

Reprinted with permission from A Time to Mourn, A Time to Comfort (Jewish Lights Publishing).

Sign up for a Journey Through Grief & Mourning: Whether you have lost a loved one recently or just want to learn the basics of Jewish mourning rituals, this 8-part email series will guide you through everything you need to know and help you feel supported and comforted at a difficult time.

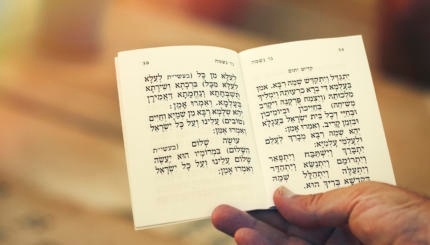

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.