This essay was the 2005 winner of The Whizin Prize, an essay contest open to all students from rabbinical training institutions around the world.

A cochlear implant is a device that is surgically implanted in the skull just behind the ear. There is also an external component to the device that is removable, and attaches to the skin above and behind the ear by means of an electromagnetic connection to the internal component. The external component has a wire connected to a receiver, which is worn behind the ear and looks somewhat like a conventional “behind the ear” hearing aid.

A Remarkable Transformation

The cochlear implant is designed to provide deaf individuals with the ability to hear some sounds. Although it is sometimes alluded to as a “cure” for deafness, it does not restore full hearing. At best, a cochlear implant permits a deaf individual to have access to auditory information, including environmental sounds, and to acquire speech skills with the proper intervention.

In the best-case scenario when the implant is successful, the transformation in an individual can be remarkable. A cochlear implant coupled with speech and listening therapy and training may ultimately help an individual to function like a hard-of-hearing, and in some cases, like a hearing person. A deaf person can learn to speak intelligibly, understand spoken language, and in some exceptional cases, to talk on the phone. In short, the medical community contends that individuals with a cochlear implant have the potential to assimilate into hearing society with increased opportunities to take full advantage of all that society has to offer. Put another way, they contend that the cochlear implant increases the chance of improving a deaf person’s quality of life. Implicit in this idea and technology is the sentiment that a deaf person’s quality of life stands to be improved, and that auditory amplification can provide that improvement.

In the best-case scenario when the implant is successful, the transformation in an individual can be remarkable. A cochlear implant coupled with speech and listening therapy and training may ultimately help an individual to function like a hard-of-hearing, and in some cases, like a hearing person. A deaf person can learn to speak intelligibly, understand spoken language, and in some exceptional cases, to talk on the phone. In short, the medical community contends that individuals with a cochlear implant have the potential to assimilate into hearing society with increased opportunities to take full advantage of all that society has to offer. Put another way, they contend that the cochlear implant increases the chance of improving a deaf person’s quality of life. Implicit in this idea and technology is the sentiment that a deaf person’s quality of life stands to be improved, and that auditory amplification can provide that improvement.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Deaf people have reacted to this new technology in a variety of ways. There are those who see deafness as a disability and handicap, and those who do not. The medical community typically views deafness as a pathology and as an aberration. In this view, deafness is seen as a disability. According to this view, since people are expected to be able to hear, those who are unable to hear must have something wrong with them.

The deaf community or “Deaf culture/ Deaf world” asserts that deafness is not a disability; it is simply a part of the self, an aspect of identity. Members of Deaf culture self-identify as a culture under the rubric of a shared history, shared experience, and shared language. Within Deafculture, American Sign Language or ASL is the predominant language. The sharedexperience of Deaf culture consists not only of the shared minority experience of beingdeaf in a majority hearing world, but also of shared social norms and customs.

Jewish Bioethical Perspectives

From a Jewish bioethical perspective, the cochlear implant is in a category by itself. The fundamental distinguishing feature between the cochlear implant and other medical procedures is that the cochlear implant is surgically implanted in individuals who are deaf, but otherwise completely healthy. Although Jews are commanded to break every Jewish law, except for those against murder, idolatry, and incestuous or adulterous sexual intercourse, in the interest of saving a life,deafness is not a life-threatening condition.

In the Jewish tradition, since the human body belongs to God and is created in the image of God, we have a responsibility to safeguard and protect the body. Dorff writes that, “we are obligated to avoid danger and injury…Jewish law views endangering one’s health as worse than violating a ritual prohibition.”This sentiment raises the question of whether deafness, as a non-life threatening condition, merits the risk of surgery, and specifically, surgery on the head and skull. Furthermore, surgery is required not only for the initial placement of the implant, but is necessary after implantation as well, as in the cases of internal component failure or breakage.

Different writers in the field of Jewish bioethics have commented on some of the different situations that qualify as “appropriate” surgical risks, and what level of risk is considered “appropriate” in specific situations. Both Dorff and Freedman have noted that it is considered within the province of taking care of the body to risk, “pain and wounding,” or surgery, to achieve what one considers to be an improved state. Freedman notes, “a person is permitted to choose to undergo a degree of self-wounding and pain on behalf of that which he or she judges to be a greater good.” However, Freedman also notes that while, “pain and wounding may be permissible toward this end, serious risk to life is not.”The evidence suggests that the risks encountered during the cochlear implant surgery itself are not great enough to render it impermissible on those grounds.

On the other hand, there are remaining questions about the potential effects of long-term implant use. The potential for ill effects may actually render the risk of implantation too great to be considered permissible according to Jewish law. Information about this risk is simply not available at this time. Because Jewish law exhorts us to safeguard and protect the body, and in particular, to avoid danger and injury, the question of whether the risks entailed by long term use of the cochlear implant are at an acceptable level, must be discussed.

Jewish law obligates us to help those who are sick or suffering and to heal whenever possible. With respect to this obligation Dorff writes, “[b]ecause God owns our bodies, we are required to help other people escape sickness, injury, and death.” And, “we have a universal duty to heal others because we are all under the divine imperative to help God preserve and protect what is God’s. “In addition, Judaism teaches that God “upholds the cause of the fatherless and the widow,”and instructs us to do the same. Astor points out that the disabled or handicapped were typically included in the category of the “weak and defenseless.”

In short, Judaism teaches people to help the handicapped, which according to Jewish law, includes the deaf. Certainly proponents of the cochlear implant feel that they are doing exactly that in accordance with all of the principles of bioethics. Their perspective is that one’s quality of life is substantially enhanced by virtue of being able to hear. If this view is correct, then from a Jewish bioethical perspective, a cochlear implant may not only be permissible, but also laudable in its attempt to help the deaf.

By contrast, since the most vocal members of Deaf culture don’t see their deafness as a “broken” part of the self but simply as another aspect of themselves, any perceived attempt to “fix” that part of the self, which isn’t broken in the first place, may be viewed as disrespectful at best and insulting at worst. Insult is clearly forbidden in the Torah in both the pshat and drash of Leviticus 19:14, “You shall not insult the deaf.” Furthermore, attempts to “fix” deafness could be considered an affront to God.

Dorff, however, asserts therabbis’ teachings that a physician has not only God’s authorization, but also a moral and divine obligation to heal.Since those in the medical community view deafness as a defect, something that is broken, they believe they are justified in doing what they can to “fix” it. A logical conclusion of this argument is that, since we act “as God’s partners in the ongoing act of creation,”43 the medical community is working with God to “make the deaf hear.” One might even suggest that this process is helping to repair the world (tikkun olam), and that it is helping to fulfill the biblical prophecy that in the world to come (olam haba), “the deaf shall hear even written words,” and, “the ears of the deaf shall be unstopped.”

On the other hand, Exodus 4:11 states outright that God created deaf people on purpose. Exodus 4:11 reads, “[a]nd the LORD said to him, “Who gives man speech? Who makes him dumb or deaf, seeing or blind? Is it not I, the LORD?” One possible reading of this verse is that God created deaf people to experience life as such, as a deaf person, and divine providence in that respect ought not to be challenged. From one Jewish perspective, perhaps the goal vis a vis deaf people ought not to be to attempt to “fix” deafness, but to attempt to “fix” society’s attitude with respect to deaf people. This would entail finding ways to make society as a whole more accessible to all those who are different, including those who are deaf. According to this viewpoint, it is possible to see the focus on “fixing” deafness asmisdirected.

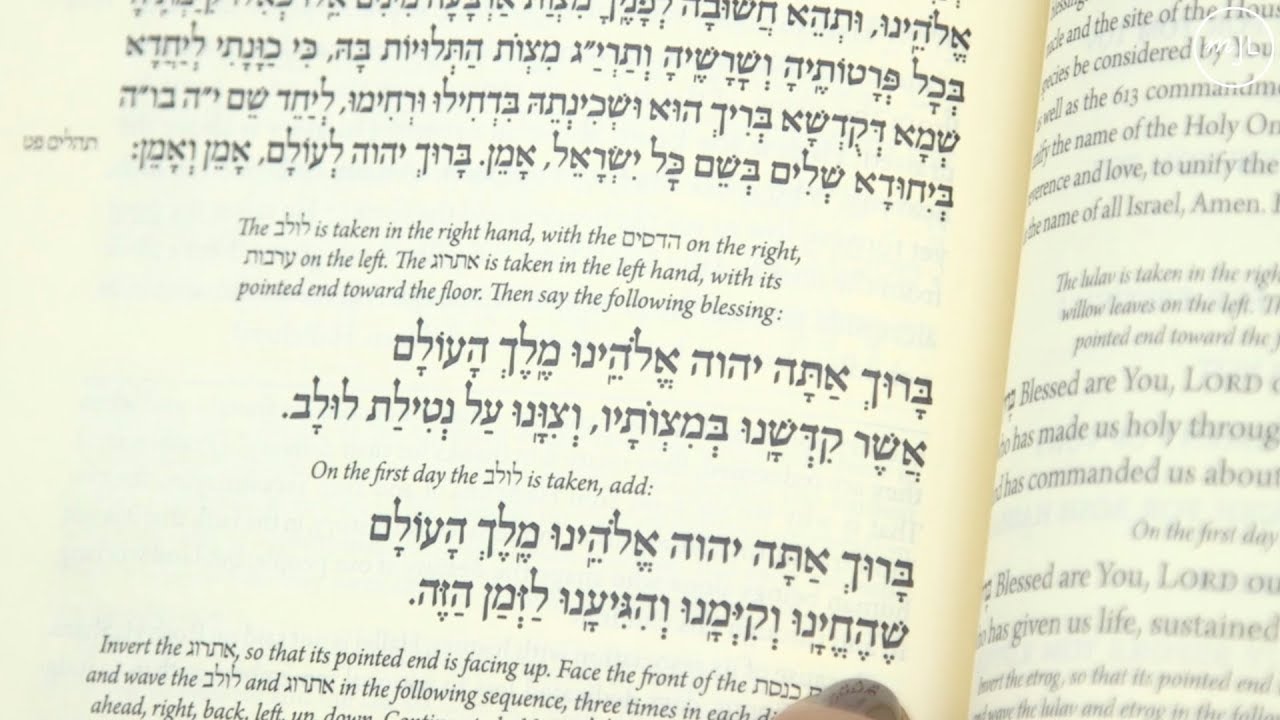

Finally, relevant to the issues of deafness, difference, and the cochlear implant is the idea that Judaism teaches us to recognize the divine image inherent in all persons, including those who are different or disabled. To this end, there is a blessing (bracha) Jewish people are traditionally taught to say when they see someone who is different, or who has a disability. Dorff translates the brakha, which reads Barukh ata adonai elohaynu melekh ha-olam m’shaneh habriyot,as, “Praised are you, Lord our God, who makes different creatures,” or “who created us different.”Astor offers the following translation, “Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, who makes people different.”

The medical community does not cherish sign language, the deaf experience, or any of the elements of Deaf culture. One might argue that the medical community is so focused on “fixing,” “curing,” and eliminating deafness, that they do not see the inherent divinity in deaf people, and the divine worth of the language and culture the deaf experience has created. This runs counter to the principle behind reciting m’shaneh habriyot and the lessons learned by doing so: namely, that there is a spectrum of human diversity on the planet and that all of this diversity reflects divinity

The responsibility of Jews with respect to the cochlear implant is only to make sure that individuals considering this medical procedure have access to all of the relevant information from the medical community, the Deaf community, and from within Jewish tradition. Once this is done, others should step back and respect the divine image within those individuals, and allow them the space and freedom to reach their own conclusions and make their own decisions.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.